In this post, Steph continues her look into the depiction of syphilis in art throughout the years.

For more information on the Art, Health and History project, click here.

Some of the remedies for syphilis and the more complacent attitudes which some people developed towards the disease can be viewed in some of Hogarth’s works in our current Prints of Darkness exhibition.

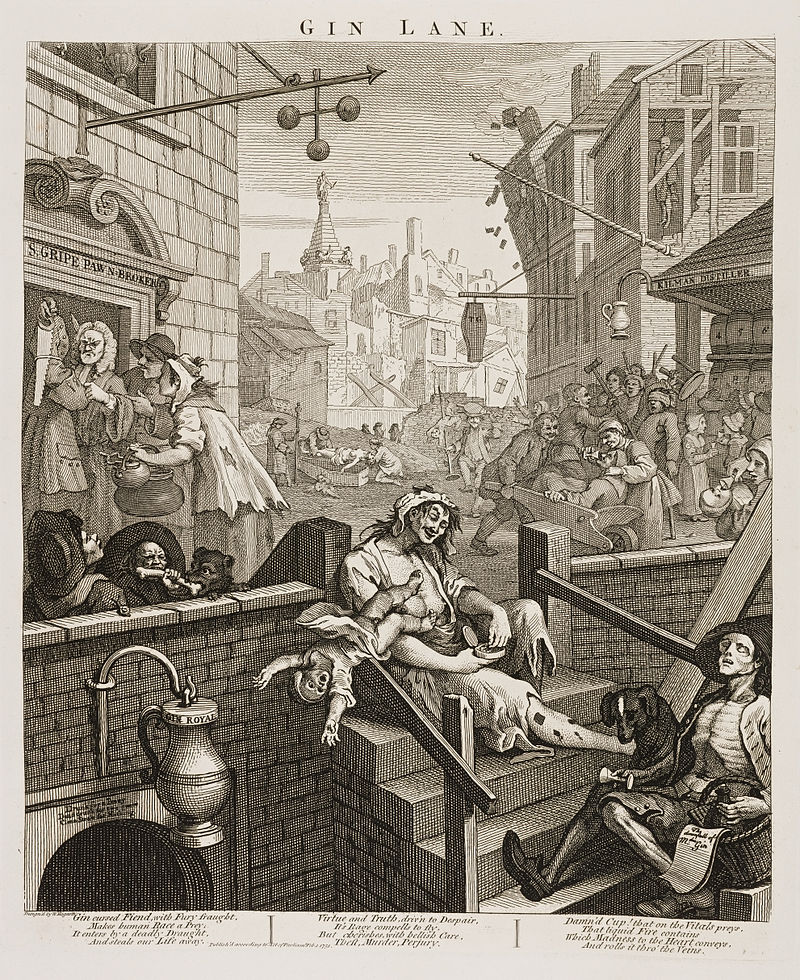

Hogarth used syphilis in many of his works to help indicate the moral corruption of the characters he depicted. The bad mother in Gin Lane, the ‘gentleman’ who loses his wig and topples to the floor in A Midnight Modern Conversation, the wayward husband and the quack he visits in Marriage à la Mode and Moll Hackabout in A Harlot’s Progress all seem to have marks caused by the disease. So do various minor characters, especially prostitutes, in his works. A Harlot’s Progress shows the ultimate progression of the disease. Moll Hackabout doesn’t lose her nose or develop gummas, but she does eventually die from the disease, wrapped in sweating blankets as a last attempt to treat the pox. Around her lie various other treatments, all ineffective.

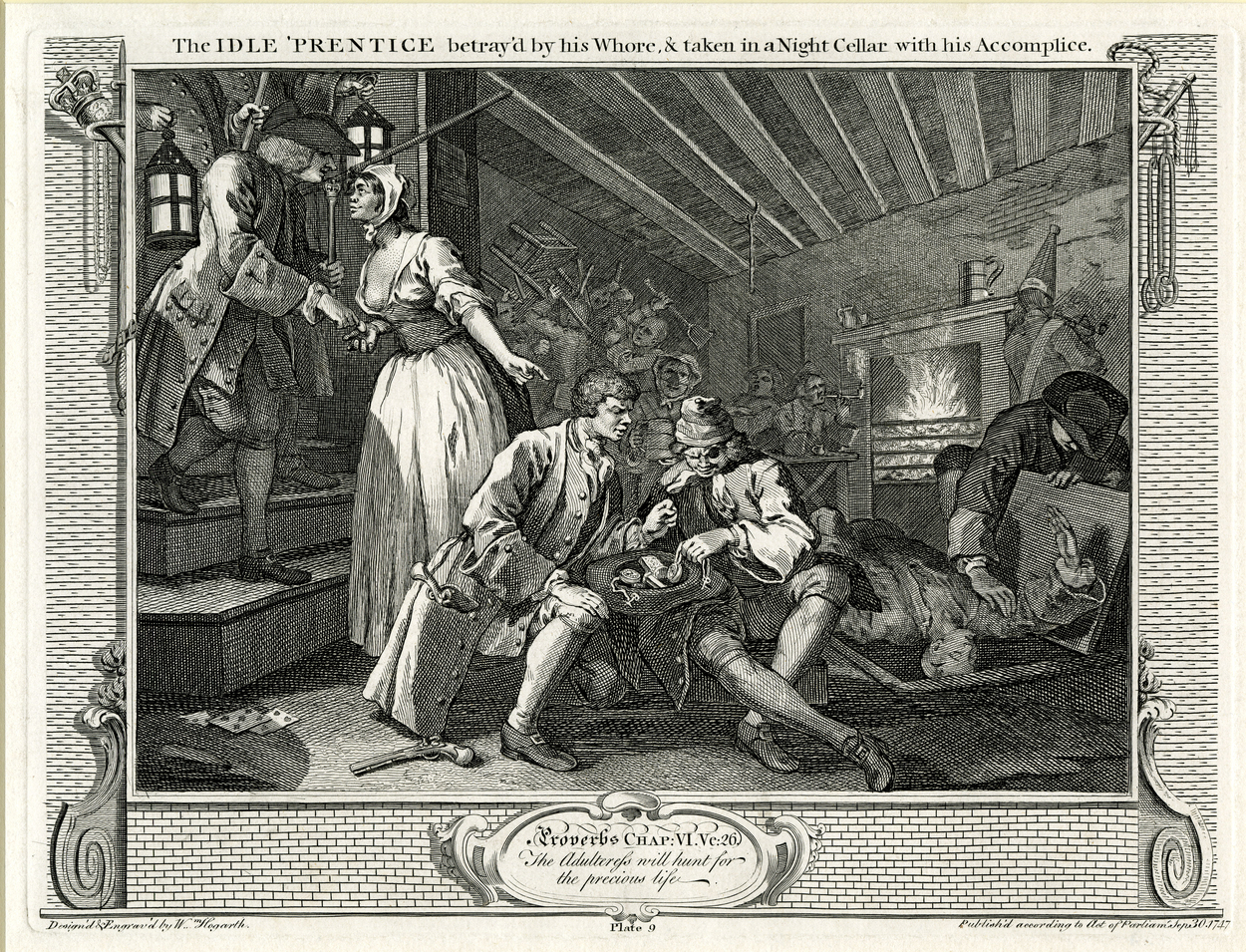

A woman serving drinks in plate 9 of Industry and Idleness sports one of the most visually alarming and more severe effects of the disease; she has lost her nose and wears a black patch to cover it up. For those who were wealthy a rather expensive prosthetic, such as the one pictured below, might offer some cosmetic relief. Ultimately, however, a missing nose was a likely sign that one had syphilis, unless they had been very obviously injured in war, thus leaving one open to censure and unpleasant reactions from others.

The wayward husband in Marriage à la Mode seems rather unconcerned as he presents a quack and his companion with a young lady he has likely infected with the disease. Perhaps he sees the disease as a trifle, even a badge of honour, as some young foolish men may have done once the initial chancre disappeared. Men might sometimes boast of having caught an infection, a ‘clap’, as a sign of their masculinity and prowess. The skull on the quack’s desk is a grim reminder of the fate of many of those infected with syphilis in a world before antibiotics. The ghastly visible effects that presented with some cases of syphilis made it especially suited to acting as a visual representation of immorality for artists. Most of the people sporting symptoms of syphilis in Hogarth’s works act in ways that would be considered immoral. It suggests that their behaviour has led to them catching the pox, except for the children. The children are innocent victims who have inherited the disease from parents who have behaved badly.

Controlling the Pox

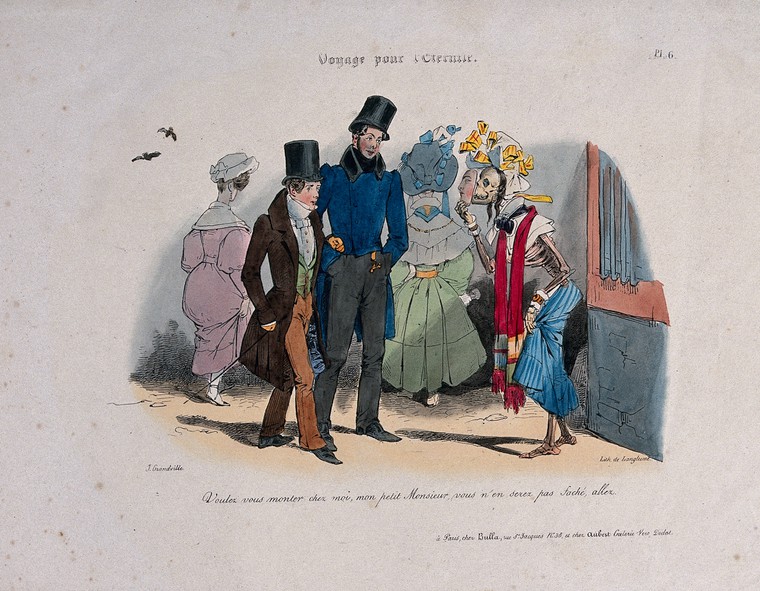

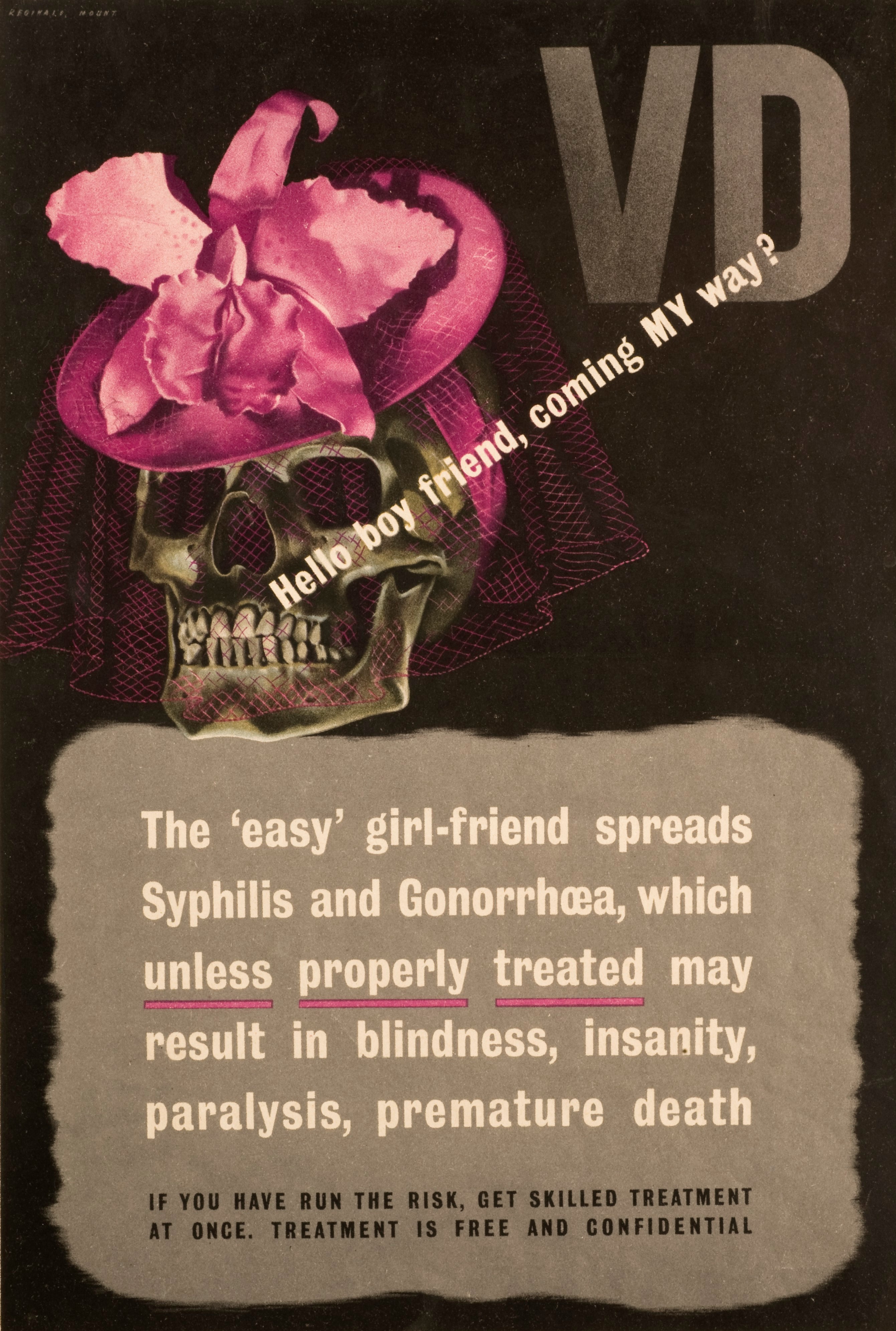

Many attempts to halt the spread of syphilis involved trying to control prostitution in some way. Henry VIII stated that the brothels in Southwark should be closed in 1546, and his father had also targeted brothels during his reign. The attention toward brothels was partly due to the ideas of immorality these places, although syphilis was also a concern. Attempts aimed at controlling syphilis began to target prostitutes very early on, since the major outbreak in Europe during the late fifteenth century. Prostitutes remained a target throughout the centuries. Trying to control prostitution makes sense; a prostitute’s work left them especially susceptible to catching syphilis and they might spread it to others. They were, however, often portrayed as villains in a sense rather than victims. Many artworks warning people about syphilis, especially from the nineteenth century onward, are directed at men, with the figure of the prostitute being the embodiment of death. The prostitute as death often appears as a skeletal being in these works.

Little blame is placed on men in these works. This is perhaps because there were concerns in many nations about men being unfit to fight in military conflicts due to venereal disease. Men who might be potential recruits or were already soldiers were often the intended target of such works, as they were likely to seek comfort from prostitutes. Another contributing factor is the fact that prostitutes or ‘fallen women’ were seen as the opposite of the feminine ideal. They were, of course, not the only women to be infected. Depictions of the prostitute as the personification of syphilis and death, concealing a deadly secret beneath a pretty appearance, continued well into the twentieth century.

After the germ theory emerged in the 1860s, a race began in the late 19th century to identify the microbes which cause certain diseases and people eventually became more optimistic about finding cures. Syphilis remained a major public health concern, especially with the advent of global conflict on an unsurpassed scale in the early 20th century. The eagerness to find a cure and to record how the effects of syphilis might vary from person to person led to experiments we would consider to be violations of a person’s human rights because those studying syphilis could not replicate its full effects by infecting animals used in labs.

Unethical Experiments

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is the most notorious of all the studies associated with syphilis, although it was not the first unethical experiment. It began in 1932 and was conducted by the Public Health Service. Its aim was to study the effects of untreated syphilis in African-American men in Macon County, Alabama, where it was noted there was quite a high incidence of syphilis. Those who conducted the study based it upon previous, badly done, studies. Their interest in the effects of syphilis on African-Americans was due to these previous studies suggesting that syphilis was more likely to display different effects on black men than it did on white men. They were influenced by no small amount of racial prejudice, evident in some of the remarks they made concerning the patients they encountered during the Tuskegee Study. They also took advantage of their status as medical professionals and the fact that many poor, rural black men would be happy to receive any kind of medical attention. African-American medical personnel were used to interact with the men in order to put any suspicions at ease and convince them to continue participating in the study.

Those who conducted the experiment did not inform the 600 men used in the study that it was about syphilis. Of those involved, around 400 were found to have syphilis. They were not told they had syphilis. All of the men involved in the study were told they were being treated for ‘bad blood’, a term which could refer to a variety of diseases. They were never told exactly what was meant by this term in the context of the study and so their informed consent was not obtained. They were asked if they would consent to an autopsy in exchange for an adequate burial. They did not actually know that the study concerned syphilis until 1972, when the press exposed the story. A lawsuit was filed on behalf of the men and their families in 1973, and a settlement was reached outside of court the following year. An official apology on behalf of the government was issued by Bill Clinton during his presidency in 1997.

Little or no treatment was administered in the study to those who had syphilis, whether it was mercury pills, Salvarsan 606, or later, Penicillin. They were, however, submitted to painful spinal taps and efforts were made to try to keep them from accessing treatment, although these efforts were not necessarily successful, and contact was lost with some of the men. Although the study was initially only supposed to last for a short time before treatment was administered to those who actually had syphilis, public health officials kept managing to extend the study and so it continued for forty years.

The Tuskegee Study is perhaps the most notorious but is by no means the only unethical experiment to involve syphilis in the twentieth century. One such experiment only recently came to light. In 2010 Barack Obama gave an apology to the president of Guatemala due to the unethical nature of the Guatemala Experiment, which had been largely unknown until that point. From 1946-1948 US medical researchers conducted a study including orphans, prostitutes, patients from psychiatric units, and soldiers. John C. Cutler, a scientist working for the United States Public Health service had been involved in the Terre Haute study which aimed to examine methods of gonorrhoea prevention after infecting subjects, in this case prisoners, with the STD. He also later became a prominent figure in the Tuskegee Study. It was historian Susan M. Reverby’s examination of Cutler’s papers after his death that ultimately led to them being placed in the hands of the federal government after they were examined by the Centre for Disease Control.

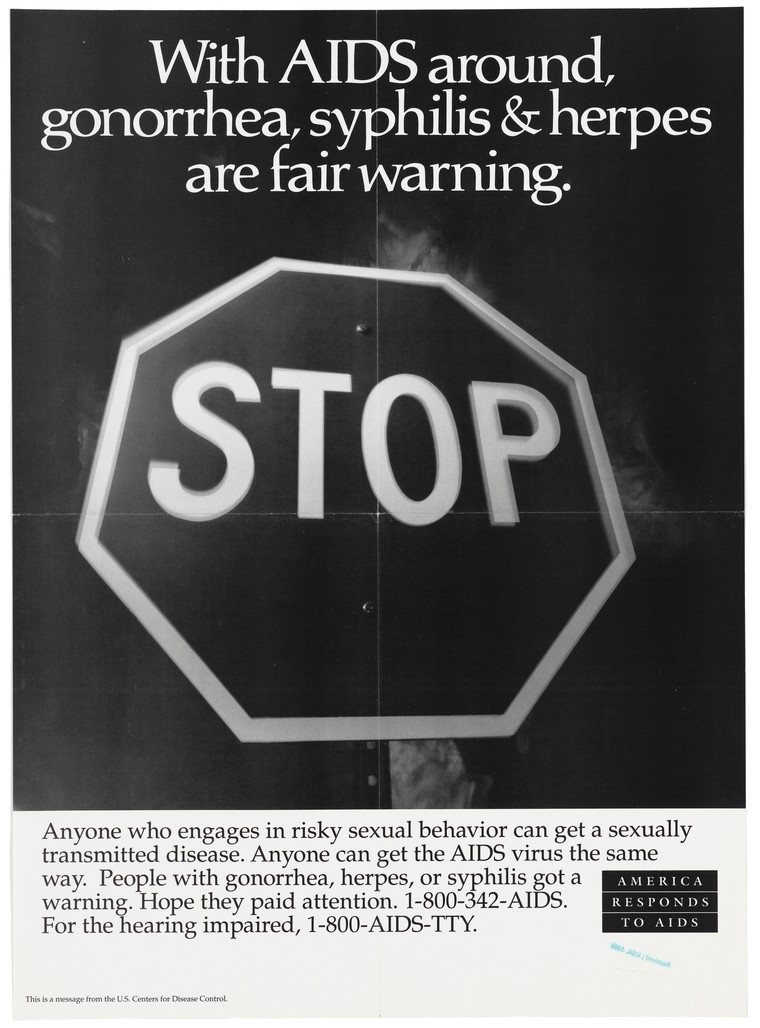

The spectre of syphilis in the 20th century didn’t disappear with these experiments. Although antibiotics such as Penicillin were proven to work against the disease, the memory of syphilis as a deadly illness without effective treatment was prominent enough that it was sometimes spoken of as a ‘warning’ when the HIV epidemic became known in the later 20th century. Parallels have been drawn by historians between the history of syphilis and HIV, hardly surprising given the stigma that has surrounded them both. Although we like to think of ourselves as more enlightened than those who have gone before us, whenever we are faced with a new disease or a recurrence of a disease we thought to be something of the past, we sometimes fall back into ways of behaving (such as persecuting others) that we might normally condemn. Death and disease are ever at hand to provide us with rather uncomfortable insights into human nature.

Resources

https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

https://catalog.archives.gov/search?q=tuskegee

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/oct/01/us-apology-guatemala-syphilis-tests

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/08/guatemala-victims-us-syphilis-study

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/30/guatemala-experiments

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/x4y6qs7s?query=syphilis&page=2

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/m3ttr8jp?query=ulric%20von%20hutten%20syphilis

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/z9nbca2a?query=syphilis&page=2

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/juutsssc?query=durer%20syphilis

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/edzbqu78?query=syphilis%20fracastorius

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nhjzetht?query=mercury%20pills

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/qw9dd5g5?query=straet%20syphilis

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/p6zhruvz?query=nose%20syphilis

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cefqer5v?query=%20syphilis&page=2

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3413456/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1079501/

https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b28139938#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=12&z=-1.2498%2C-0.0887%2C3.4997%2C1.7731

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A40375.0001.001?view=toc

http://notchesblog.com/2016/03/22/sores-scorn-and-stigma-suffering-syphilis-in-early-modern-germany/

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio/artists/gerard-de-lairesse

http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC1194440&blobtype=pdf

Peter Lewis Allen, The Wages of Sin: Sex and Disease, Past and Present (London, 2000).

Catherine Arnold, City of Sin: London and Its Vices (London, 2010).

Lawrence I. Conrad, Michael Neve, Vivian Nutton, Roy Porter, Andrew Wear, The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge, 2003).

Hugh Crone, Paracelsus: The Man Who Defied Medicine (Melbourne, 2004).

Barbara J. Dunlap, ‘The Problem of Syphilitic Children in Eighteenth-Century France and England’, in Linda Evi Merians (ed.), The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Kentucky, 1996), p. 114- 127.

John Frith, ‘Syphilis- Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins’, Journal of Military and Veteran’s Health 20:4

Fred D. Gray, The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: The Real Story and Beyond (Montgomery, 2013).

James H. Jones, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (New York, 1993).

Fiona Haslam, From Hogarth to Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth Century Britain: (Liverpool, 1996).

Debora Hayden, Pox: Genius, Madness and the Mysteries of Syphilis (New York, 2003).

Darin Hayton, ‘Joseph Grünpeck’s Astrological Explanation of the French Disease’ in Kevin Siena (ed.), Sins of the Flesh: Responding to Sexual Disease in Early Modern Europe (Toronto, 2005), pp. 81-109.

N.F. Lowe, ‘The Meaning of Venereal Disease in Hogarth’s Graphic Art’, in Linda Evi Merians (ed.), The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Kentucky, 1996), pp. 168-182.

Marie E. McAllister, ‘John Burrows and the Vegetable Wars’, in Linda Evi Merians (ed.), The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Kentucky, 1996), pp. 85-102.

Linda E. Merians, ‘The London Lock Hospital and the Lock Asylum for Women’, in Linda Evi Merians (ed.), The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Kentucky, 1996), pp. 128-148.

Kathryn Norberg, ‘The Body of the Prostitute: Medieval to Modern’, in Sarah Toulalan and Kate Fisher (eds.), The Routledge History of Sex and the Body: from 1500 to the Present (London, 2013), pp.393-407.

J.D. Oriel, The Scars of Venus: A History of Venereology (London, 1994).

Monika Pietrzak-Franger, Syphilis in Victorian Literature and Culture: Medicine, Knowledge and the Spectacle of Victorian Invisibility (Hamburg, 2017).

Gabriel A. Rieger, Sex and Satiric Tragedy in Early Modern England: Penetrating Wit (Farnham, 2009).

Claudia Stein. Negotiating the French Pox in Early Modern Germany (Warwick, 2009).

Richard M. Swiderski, Quicksilver: A History of the Use, Lore and Effects of Mercury (Jefferson, 2008).

Perry Treadwell, God’s Judgement? Syphilis and AIDS: Comparing the History and Prevention Attempts of Two Epidemics (New York, 2003).

Judith R. Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class and the State (Cambridge, 2001).

Philip K. Wilson, Surgery, Skin and Syphilis: Daniel Turner’s London (1667-1741), (Amsterdam, 1999).

Philip K. Wilson, ‘Exposing the Secret Disease: Recognising and Treating Syphilis in Daniel Turner’s London’ in Linda Evi Merians (ed.), The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Kentucky, 1996), pp. 68-84.

One thought on “Art, Health and History. The Great Pox Part Three: Behaving Badly.”