Have a peek at some of the gods, heroes, monsters, and other strange creatures you may encounter at the gallery this October in this post compiled by Steph.

I hope this October finds you well and truly getting into the spirit of Halloween! It’s a time I’ve loved ever since I was a child. During my childhood we had a very obliging black cat, who I loved to show off to anyone who would let me rattle on about him. Naturally, I was nearly always a witch for Halloween- after all, I had to dress to match my friend!

There aren’t any black cats or witches currently gracing the walls of the Whitworth but there are still plenty of interesting characters to spot this month. Let’s have a closer look at some of them.

The Werewolves

The tale of Lycaon is one of the oldest werewolf stories we know of. The oldest recorded werewolf story comes from the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which Gilgamesh refuses the advances of a woman because she turned her previous lover into a wolf. In the tale of Lycaon, the man who is about to be transformed takes centre stage. According to Ovid, King Lycaon of Arcadia lived during a time when humanity had descended into depravity and was known for his penchant for cruelty. One day he was visited by the god Jupiter, who had disguised himself as a human to see the depths humans had sunken to.

When he travelled to the home of Lycaon and revealed himself as a god, Lycaon’s people bowed and began to pray to Jupiter but Lycaon mocked their show of piety. The tyrant doubted that Jupiter was who he claimed. Lycaon decided to test whether Jupiter was a god or a mortal by attempting to have his guest killed- but not before serving him a gruesome feast of human flesh. Recognising the meal at once for what it truly was, Jupiter set out to punish Lycaon by transforming him into a wolf:

‘Terror struck

he took to flight, and on the silent plains

is howling in his vain attempts to speak;

he raves and rages and his greedy jaws,

desiring their accustomed slaughter, turn

against the sheep—still eager for their blood.

His vesture separates in shaggy hair,

his arms are changed to legs; and as a wolf

he has the same grey locks, the same hard face,

the same bright eyes, the same ferocious look.’ – Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More Edition. Perseus Digital Library.

This big, bad and somewhat stylish wolf is one many of us have met in childhood; the wolf who wants to devour Little Red Riding Hood. Charles Perrault is believed to have been the first person to have published the story of Little Red Riding Hood, in a collection of fairy tales, in 1697. However, as with many fairy tales, its exact origins are hard to pin down and multiple versions exist. Perrault’s version of the tale is a cautionary one entirely without the happy ending modern audiences are used to. Walter Crane’s version occupies a middle ground between the ending in the version told by Perrault and the ending modern audiences are used to thanks to the Brothers Grimm (which has both Red Riding Hood and her grandmother devoured but ultimately unharmed). Crane’s version of the tale ends well only for Red Riding Hood, who is saved by a hunter.

Lycaon and two proofs by Walter Crane of Red Riding Hood’s Picture Book have been selected for display by (Un)Defining Queer project participant Bria. The werewolf has been viewed by some academics as a metaphor for queerness because of its liminal existence, which renders it an outsider.

If you’re interested in seeing these werewolves in person, why not head up to the (Un)Defining Queer exhibition?

You can find out more about werewolf stories and the werewolf trials of early modern Europe, in addition to how humans have made a villain of the wolf throughout the centuries, in this post by Matthew: Little Red Riding Hood, Woods, Wolves and Wild Places.

Greek and Roman Deities

Thomas Burke’s Diana and Callisto can be found on display in our (Un)Defining Queer exhibition. Callisto, shown here in Diana’s (or is that Jupiter’s?) embrace was, according to some version of the story a nymph who served as an attendant and companion to the goddess Diana. Other versions of the myth claimed that Callisto was a daughter of Lycaon. Burke’s engraving perhaps refers to what some have referred to as the more ‘comical’ version of the myth concerning Diana and Callisto, in which Jupiter disguises himself as Diana to seduce Callisto and get her to forsake her vow of chastity.

Callisto is usually transformed into a bear by an angry goddess, sometimes Juno and sometimes Diana herself depending on which version of the myth you hear, and she is eventually cast into the sky by Jupiter- thus becoming the constellation Ursa Major or The Great Bear.

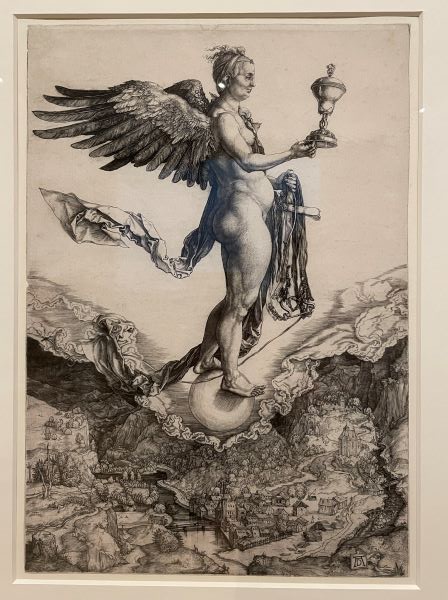

According to some ancient poets, the Nemesis who was the daughter of Nyx (Night) laid an egg which hatched to reveal Helen of Troy.

Nemesis also existed as a personification of disapproval and the arrogance of humans. In Dürer’s engraving this goddess of retribution, balanced upon a sphere, flies above a town in an Alpine landscape. In one hand she holds an ornate goblet, in the other a bridle- perhaps to curb human ambition and pride.

You can see Nemesis and Dürer’s other Meisterstiche in person in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World.

If you fancy getting a bit crafty, you can download our free colouring sheet of Nemesis here.

Pegasus

Fans of My Little Pony will be pleased to know that they can see the Renaissance original at the gallery this October. Winged though he may be, this Pegasus doesn’t look like he will be flying anywhere. A son of Poseidon, Pegasus and his lesser-known brother Chrysoar (who was often depicted as a young man but occasionally as a winged boar) sprang from the blood of the decapitated gorgon Medusa. How’s that for an origin story?

Although Perseus facilitated the birth of Pegasus by decapitating his mother, it was the hero Bellerophon who would be the first to ride the winged steed during his battle with the Chimera. Pegasus would later get his own constellation. This rather adorable portrayal of Pegasus was produced by Jacopo de’ Barbari, a Venetian artist who was acquainted with Albrecht Dürer and worked as a court painter for the Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I and later Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, followed by Philip of Burgundy.

The Four Horsemen

The Four Horsemen isn’t the only part of Albrecht Dürer’s The Apocalypse (1498) series on show in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World but, of the five pieces from the series we have on show, this is the one that takes centre stage. Here we see (from top to bottom) the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in action; first is the Conqueror, followed by War, Famine and an emaciated Death.

One of the key features that distinguishes the Four Horsemen in the Book of Revelation is the colour of the horses they ride: a white horse for the Conqueror, red for War, black for Famine and a pale horse for Death. As Dürer’s woodcuts lack colour, the easiest way to distinguish them is by the tools and weapons they carry; a bow for the Conqueror, a sword for War, and a set of scales for Famine. Death has been given an interesting addition of a pitchfork, which is not mentioned in the Book of Revelation.

Another interesting detail to keep an eye out for sits in bottom corner to our left. Sinners from various walks of life are drawn into the bestial mouth of hell, with flames licking at them, whilst simultaneously being trampled by the mounts of the Four Horsemen. And that’s only the start of the party!

Of course, the real print is much bigger and impressive than the small image we have included here, so why not have a gander at The Four Horsemen and other pieces from The Apocalypse in person this October?

The Scarlet Beast

Part of Dürer’s The Apocalypse (1498) series, The Babylonian Whore depicts the titular temptress sat atop a seven-headed, ten-horned beast. This walking nightmare of a creature is the beast which serves as the mount of the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation and its description makes us think it must a have a right mouth (or many mouths) on it:

‘And I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast, full of names of blasphemy with seven heads and ten horns. The woman was garbed in purple and scarlet, and gilded with gold, gems, and pearls, and bearing a golden goblet in her hand full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication.‘ – Book of Revelation (17:3—4)

Some would jest that all this makes the creature quite the party animal- but I can’t quite shake the Jim Henson induced trauma of my childhood to see it that way. The Dark Crystal, anyone?

Sea Gods and Monsters

A variety of ocean dwelling gods, monsters and tritons are on display at the gallery this October.

Dürer’s engraving The Sea Monster, or Das Meerwunder as the artist referred to it in his diary, depicts a nude woman being abducted by a creature with the head and torso of a man and the tail of a fish. The monster has the curious addition of an antler protruding from the top of his head. He carries a shield fashioned from a turtle shell and a bone.

It has been suggested by some scholars that The Sea Monster is a version of the Rape of Europa or a depiction of a fable from Ovid’s Fasti in which a woman is abducted by a river god called Numicius. However, others have suggested that The Sea Monster may refer to a myth in which Theudelinde, a Langobard queen, is abducted by a sea monster.

Mantegna’s engraving depicts a battle between sea gods and tritons. In Greek mythology, Triton himself was a sea god. He was a son of Poseidon and the nymph Amphitrite. He appeared as a being who appeared to be half human and half fish.

There were also other beings referred to as tritons, who also appeared half human and half fish- sometimes with horse-like features too, such as the forelegs Mantegna gave to his tritons and sea gods. They appear to be brandishing bones as weapons or in an effort to intimidate one another. Nereids or sea nymphs ride upon the backs of these bizarre and fierce creatures, which seem to be the ocean’s equivalent of centaurs.

Dürer observed this print closely in order to produce a drawing in 1494, which helped provide a starting point for The Sea Monster.

Mantegna is said to have used the physique of the Horse Tamer sculptures at Quirinal Hill in Rome, which are believed to date back to the 4th century and are copies of the original Greek sculptures, as inspiration for the muscular physique of his tritons and sea gods.

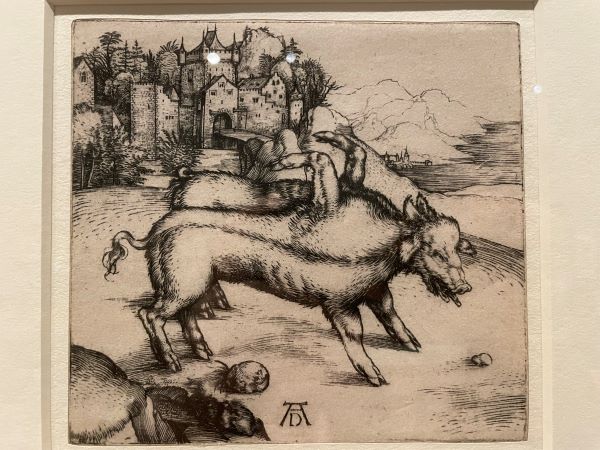

The Monstrous Pig of Landser

Spare a thought for this poor little piggy. Born in March 1496 in Landser, in the Alsace region, what became known as the ‘monstrous pig of Landser’ wouldn’t have been nearly as intimidating as the animal depicted in Dürer’s woodcut print. The real pig was merely a piglet and she (the animal was said to be a sow) wouldn’t have survived long. According to a broadside written by Sebastian Brandt, the animal had one head, four ears, two tongues, two bodies and eight legs- six of which would have touched the ground.

Such ‘monstrous’ or ‘wondrous’ births were often interpreted as omens, which perhaps explains the more intimidating visage that greets you in Dürer’s depiction of the unfortunate creature. The Monstrous Pig is currently on display in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World at the Whitworth, which runs until March 2024. If you have a soft spot for pigs, you can spot some less unusual but equally impressive specimens in Dürer’s The Prodigal Son.

You can download a free colouring sheet of The Monstrous Pig here.

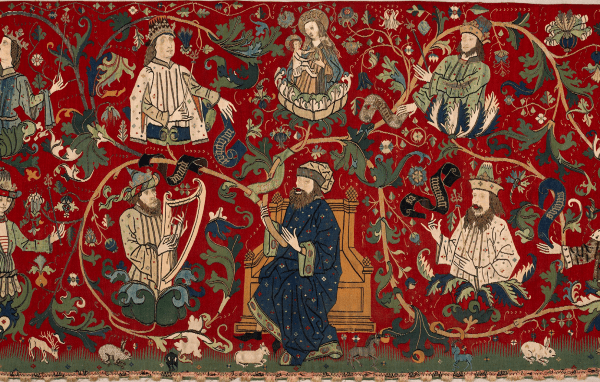

A Miniature Menagerie

Overshadowed by the Tree of Jesse on this magnificent altar frontal has a veritable miniature menagerie below the throne consisting of lambs, rabbits, stags and even a unicorn! In each corner of the piece there sits a symbol of one of the Four Evangelists. Dating back to the 1470s, the altar frontal was woven with linen, silk and gold and silver thread and originates from Cologne.

The rabbits look rather displeased and conjure up images of the vicious rabbit from Monty Python and the Holy Grail for me. Perhaps they are there to represent fertility? I really have no idea.

The inclusion of a unicorn is particularly interesting for me. This creature is easily missed because of his colouring- but what a horn he sports! In medieval bestiaries the unicorn was likened to Christ and his horn was said to represent the unity of the father, son and holy spirit. If you’re interested in learning more about unicorns as they appear in art and bestiaries, you can read all about it here.

The Devil Himself

Lurking in the shadows of another one of Dürer’s Meisterstiche is the Devil himself- but perhaps not as you are used to seeing him. This Devil has the snout of a pig and long jowls, which look like the wattles of a rooster. The horns of a ram protrude from either side of his head, which is topped with a crest and what appears to be either an antler lacking tines or a single horn. He is a combination of many bestial features, rendered by the artist in disturbing and fascinating detail.

The Devil in Knight, Death and the Devil stalks the steadfast knight, who continues his way despite being trailed by evil personified and confronted by Death. Would you care to meet this Devil on your next visit to the Whitworth?

Resources

Colour Our Collections: Nemesis by Albrecht Dürer

Colour Our Collections: The Monstrous Pig by Albrecht Dürer

Entry from the #WhitworthBestiary: Little Red Riding Hood: Woods, Wolves and Wild Places (10/03/21)

Entry from the #WhitworthBestiary: Unicorns: Not All Glitter and Rainbows (25/03/21)

Walter Crane (1875). Little Red Riding Hood. George Routledge & Sons. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.446713.39088007509888

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More Edition. Perseus Digital Library, Gregory R. Crane (editor), Tufts University.

Jane Campbell Hutchinson. Albrecht Dürer: A Guide to Research (New York, 2000).

Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art (The University of Chicago Press).

The Book of Revelation: http://www.readbibleonline.net/?page_id=274

University of Pittsburgh, Perrault: Little Red Riding Hood, taken from Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book (London, ca. 1889), pp. 51-53