Explore some of Albrecht Dürer’s engravings depicting the Virgin Mary. Read about Nuremberg’s relationship to the Virgin and find out what Dürer got up to around the festive period from shopping to dodging plague and other dangers.

You can buy some of the books mentioned in the bibliography, including the catalogue for the Albrecht Dürer’s Material World exhibition (which is on display at the Whitworth until March 2024), online and in person at The Whitworth Shop.

Dürer and the Virgin Mary

At the heart of traditional Christmas celebrations is a story we have all encountered at some point. It is the story of the baby Jesus, from the divine Annunciation to the his birth in Bethlehem. For Albrecht Dürer and many other artists who lived during the 15th and 16th centuries the story was not only a familiar tale and something which would have influenced what they did at this time of year, it was also something which they depicted in beautiful works of art. In Albrecht Dürer’s Material World, on display at the Whitworth at the time of writing until March 2024, Dürer’s Life of the Virgin series, as well as his The Virgin by the Wall and The Virgin seated on a Grassy Bank can be viewed.

Also included in the exhibition is a piece by Martin Schongauer (born sometime between 1440-1453, died 1491 CE), titled The Annunciation. It is not the only work by Schongauer to depict the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary. We know that Dürer admired Schongauer’s work and had hoped to meet him, but Schongauer died before Dürer reached Colmar in 1492.

Both Annunciation pieces displayed in the exhibition contain lots of fine details, though Dürer’s seems to contain more. The badger-headed devil lurking under the stairs is probably my favourite detail in his Annunciation. I like badgers and I think it’s a fun detail. Both Dürer and Schongauer were aware of the potential of transmitting ideas via prints to a much wider audience than could be reached by paintings. It was not only possible to print many reproductions from a copper plate used for an engraving or from a wooden printing block for a woodcut, but the prints would also be much cheaper to buy than a painting and therefore find a place in the homes of many more people.

Some of the symbolism present within both Annunciation prints and other religious prints by Dürer and Schongauer would be easily recognised and understood by those in the late medieval and early modern periods. In today’s more secular world, the inclusion of a lily in both Annunciation pieces might be a bit puzzling to some but the audience Dürer and Schongauer were creating art for would know that the potted lily in both works symbolised the purity of the Virgin Mary.

Within the home of those who purchased prints, both Annunciation scenes and other prints produced by Dürer and Schongauer would not only serve as a reminder of the great skill of these artists but also remind the household of the importance of the stories and ideas behind them. In a way, you could argue that this also kept the story so associated with Christmas in our minds alive throughout the year. I think keeping the Christmas spirit alive through art is more preferable to the ‘Christmas in July’ marketing some shops bombard us with today.

In fact, it was not only Christmas which was celebrated in medieval and early modern Europe in many areas before the Reformation; many feast days were kept, including a feast day for the Annunciation. Dürer’s home city of Nuremberg was an imperial city and one of the most powerful cities within the Holy Roman Empire. According to historian Bridget Heal, who has written about the cult of the Virgin Mary in early modern Germany and within Nuremberg itself, the cult of the Virgin Mary was very prominent in Nuremberg and each church would have an altar dedicated to her. Heal notes that several feast days devoted to Mary were observed there prior to the Reformation, some of which (like the Annunciation) were kept after the city council opted to accept the Lutheran Reformation.[1] The Virgin Mary was depicted throughout Nuremberg in ecclesiastical and secular buildings and representations of her were common throughout the city both before and after the Reformation.[2]

We know that Dürer himself produced various depictions of the Virgin Mary in different years throughout his career as an artist, such as The Virgin Seated on a Grassy Bank (pictured above). Perhaps this was due to the influence of the cult of the Virgin in Nuremberg and his own personal faith, as well as the appeal of such prints to people who bought his prints.

Dürer’s Winter Errands in Venice

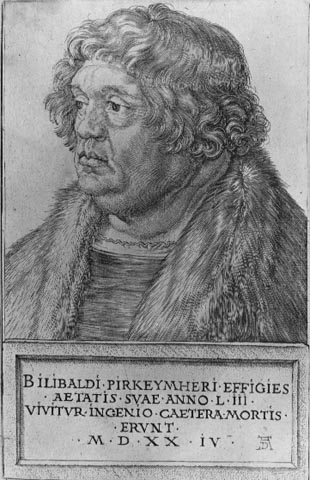

As for what Dürer was doing around any given day in the liturgical calendar, particularly around Christmas, thanks to his writings from his travels we do have an idea of where he was and what he was doing around the festive period in certain years. In 1505, Dürer travelled to Italy and stayed in Venice. A letter to his friend Wilibald Pirckheimer reveals what he was doing in January 1506, which appears to have been a lot of shopping in addition to working on an altarpiece for the chapel of San Bartolomeo (Saint Bartholomew). The altarpiece in question was The Feast of the Rose Garlands, which is in the collection of the National Gallery Prague. A high-resolution image can be viewed on their website.

Dürer’s letter ‘Given at Venice on the day of the Holy Three Kings’ (Epiphany, which falls on the 6th of January), discusses his (at that point) fruitless search for pearls and precious stones. [3] He had undertaken this search at Pirckheimer’s request and told his friend ‘you must know that I can find nothing good enough or worth the money: everything is snapped up by the Germans.’[4] Dürer went on to tell his friend about the dangers of being a tourist, stating:

‘Those who go about the Riva always expect four times the value for anything, for they are the falsest knaves that live there. For that reason some good people warned me to be on my guard against them. They told me that they cheat both man and beast…’[5]

He ended his letter with a friendly request:

‘Greet for me Stephen Paumgartner and my other good friends who ask for me.'[6]

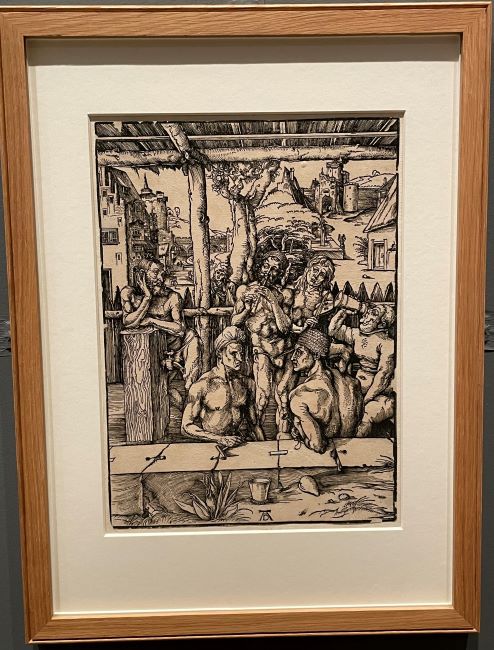

Stephen Paumgarnter, his brother Lukas and Wilibald Pirkheimer may be some of the men who are shown at a bathhouse with Dürer in his The Bath House, currently on loan from Ashmolean Museum and display in the Albrecht Dürer’s Material World echibition.

These requests from friends would end up taking Dürer some months to complete. It took a while for him to track down some of the specified objects. His letters from 1506 talk about a desire to find the best quality goods he could within the budget he seems to have been given.

Although unable to buy the pearls and precious stones Pirckheimer wanted Dürer to purchase and send to him in January, the artist did later have some success in finding some stones for Pirckheimer and also for Stephen Paumgartner. His letters from Venice reveal that by late February he had purchased some rings for Pirckheimer. One ring was set with an emerald and the other with a ruby and a diamond.[7] The emerald ring was apparently not what Pirckheimer was looking for, as Dürer received it back in a package sent by his friend. In March 1506 Dürer purchased another ring for Pirckheimer, which was set with a sapphire. We also know what he paid for it and that he spent a while haggling, as he wrote that ‘only after much entreaty could I get it for 18 ducats and 4 marcelli from a man who was wearing it on his own hand…as I gave him to understand that I wanted it for myself.’ [8]

It seems that this sapphire ring needed some repair, as he ended this letter from March 1506 with a note to Pirckheimer that had not sent all of the stones he had purchased on this occasion to him because he ‘could not get them all ready.’ He said more about the condition of the ring: ‘My friends tell me that you should have the stone set with a new foil and it will look twice as good again, for the ring is old, and the foil spoiled.’ [9]

Rings set with jewels were not the only goods he had been asked to purchased on behalf of Pirckheimer; a letter written in August that year speaks of ‘glass things‘ and of a search for two carpets, as well as crane’s feathers in addition to ‘Greek books‘ and paper. ‘But of swan’s feathers for writing there are plenty‘, the artist wrote, ‘How would it do if you stuck them in your hats in the meantime?’ [10]

Another letter penned in September 1506 reveals that at least some of the ‘glass things’ mentioned in a previous letter were ‘burnt glass’ and that he was still in search of two square-shaped carpets for Pirckheimer.[11] Maybe the ‘burnt glass’ mentioned here was a burning glass, which is a type of lens used to focus the sun’s rays and ignite things.

Danger in Venice

Shopping, tourist traps and painting aside, Dürer’s time in Venice was not without other concerns. Some of his complaints seem quite amusing and he may have been a bit vain or perhaps he was joking. In the same letter sent to Pirckheimer in September he commented ‘The other day I found a grey hair on my head, which was produced by sheer misery and annoyance. I think I am fated to have evil days.’ [12]

A letter penned in August 1506 tells us something about an illness present in Venice at the time:

‘Give my willing service to our prior. Tell him to pray God for me that I may be protected, and especially from the French sickness, for there is nothing I fear more now and nearly everyone has it. Many men are quite eaten up and die of it.’ [13]

Fire was also a worry. It cost him a possession but not his life in October that year:

‘Oh dear Herr Pirkheimer, this very minute, while I was writing to you in good humour, the fire alarm sounded and six houses over by Peter Pender’s are burned, and woolen cloth of mine, for which I paid only yesterday 8 ducats, is burned; so I too am in trouble. There are often fire alarms here.‘ [14]

There were dangers at home, too; the plague had come back to Nuremberg in 1505, prompting those whose could flee the city to do so. ‘My greetings to Stephen Pirkheimer and other good friends, and let me know if any of your loves are dead‘ Dürer wrote to Pirkheimer in February 1506. [15] Dürer’s mother and wife remained at home to sell his prints and manage the household. His letters from Venice show that, not only was he there partly to work, but he was conscious of the fact that he was head of the household following the death of his father in 1502 and now responsible for providing for those within his household.

He had tried to ensure that both his wife and mother would have enough money in his absence. One of his letters indicates that he was also trying to make sure that his younger brother Hans would be able to find work and develop his own artistic skills. He stated that he would have liked to take his brother to Venice but did not because their mother was afraid something might happen to Hans. Dürer himself had travelled to Italy with money he had borrowed from Pirckheimer, which he spoke of in his letters.

On a lighter note, in October he at least managed to order some carnelian beads which Stephen Paumgartner had requested for a rosary.

He would remain in Italy until the winter of 1507 and you’ll be pleased to know that there seems to be no record of him catching plague or having trouble with any more fires.

Maybe these snippets of Dürer’s letters from Venice will provide you with some inspiration as you go Christmas shopping!

Winter in the Netherlands, 1520

We get another glimpse of what Dürer was doing in winter from the diary he kept from July 1520 to July 1521 during his travels in the Low Countries, which is more like an accounting book. Dürer needed the new Holy Roman Emperor to agree to the renewing of his pension and the plague was back in Nuremberg. It was time to get out of town, on this occasion accompanied his wife Agnes and their maid Suzanne. Their journey would be partly funded by selling and using his prints as a form of payment along the way.

From late November into early December 1520 they were staying at Antwerp for a second time, when Dürer heard of a whale having been washed ashore at ‘by a great storm’ Zierikzee in Zeeland. [16] He was eager to see the body of the cetacean, which he wrote was ‘much more than hundred fathoms long; no one in Zeeland has ever seen one even one-third so long.’ [] He added ‘The people would be glad to see it gone, for it is so big they say it could not be cut in pieces and the oil got out of it in half a year.’[17]

Before he left to see the whale for himself, he took payments for some portraits and received gifts from people he had had over for dinner:

‘Stephen Capello has given me a cedarwood rosary, in return for which I was to take and have taken his portrait…I have had to dinner Tomasin, Gerhard, Tomasin’s daughter, her husband, the glass painter Hennick, Jobst and his wife, and Felix, which cost 2 florins. Tomasin made me a gift of four ells of grey damask for a doublet.’[18]

He travelled to Bergen-op-Zoom, where he bought a gift for his wife in the form of a ‘thin Netherlandish head cloth, which cost 1 florin, 7 stivers‘.[19] He also spent ‘1 stiver for eyeglasses, and 6 stivers for an ivory button; gave 2 stivers for a tip.'[20]

He left Bergen for Zeeland, accompanied by some friends, on ‘Our Lady’s Eve‘, which I think refers to the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (which falls on the 8th December).[21] At Arnemuiden in Zeeland he had an adventure:

‘As we were coming to land…just as we were getting on shore, a great ship ran into us so hard that in the crush I let everyone get out before me, so that no one but myself, George Kotsler, two old women, the sailor, and a little boy were left in the ship. When now the other ship knocked against us and I with those mentioned was on the ship and could not get out, the strong rope broke, and at the same moment a violent storm of wind arose which forcibly drove back our ship So we all called for help, but no one would risk himself, and the wind carried us back out to sea. Then the skipper tore his hair and cried aloud, for all his men had landed and the ship was unmanned.‘[22]

We can see how he coped under pressure in this account. It seems Dürer kept calm:

‘I spoke to the skipper that he should take heart and have hope in God, and should take thought for what was to be done. He said that if we could pull up the small sail, he would try if we could come again to land. So we all helped one another and pulled it half-way up with difficulty, and went on again towards the land. And when those on the land who had already given us up saw how we helped ourselves, they too came to our aid, and we got to land.‘[23]

He certainly sounds like the kind of person you’d want on your side during a crisis. Despite narrowly escaping danger, which could have ruined his Christmas plans and cost him his life, he didn’t discuss the incident much in his diary. Instead, he immediately moved on to talk about the beauty of Middelburg.

Unfortunately, he didn’t get to see the whale:

‘I wanted to get sight of the great fish, but the tide had carried it off again.'[24]

He returned to Bergen and then to Antwerp, where he met with Lazarus of Ravensburg and the factor of Portugal. He was given ‘a big fish scale, five snail shells, five copper ones, two dried little fishes and a white coral, four reed arrows and another white coral‘ by Lazarus of Ravensburg in return for three books and given ‘a brown velvet bag and a box of good electuary‘ by the factor of Portugal.[25] In return, he gave the factor’s servant ‘3 stivers for wages‘. The Portuguese representatives he had encountered in Antwerp had already been generous to the artist and his wife and given them gifts, with a Signor Rodrigo having given Agnes a green parrot.

The items given to Dürer by Lazarus of Ravensburg, and by others during his time in the Netherlands, are similar to some of the items that would be found in cabinets of curiosity or wunderkammer as they emerged later on during the mid-sixteenth century. These cabinets are sometimes described as the ‘first museums’. Some of Dürer’s purchases are also similar to the sort of things you might expect to see in a cabinet of curiosity- showing how curious Dürer was about the world around him.

One of his purchases, made sometime in or around December 1520, is particularly interesting to me. When he was back in Antwerp he wrote ‘I bought a little monkey for 4 gulden‘.[26] I could not find any other instance in which he wrote about this, which made me wonder whether the monkey was alive or dead at the time of purchase. Maybe it was not a real monkey at all, but I also think he would have noted if the monkey was not real and the material any carving of a monkey may have been made of. Perhaps I have missed something.

Dürer, as far as I am aware, did not delight in cruelty to animals. If anything, his art shows a fascination with animals and the natural world by the standards of his time.

And now here are some gifts Dürer distributed during the festive period:

‘I gave Lazarus of Ravensburg a portrait head on a panel which cost 6 stivers, and besides that I have given him eight sheets of the large copper engravings, eight of the half-sheets, an engraved “Passion”, and other engravings and woodcuts, all together worth more than 4 florins…I gave 6 stivers for a panel, and did the portrait of the servant of the Portuguese on it in charcoal, and I gave him all that for a New Year’s present and 2 stivers for a tip.'[27]

The giving of a gift for New Year’s sounds like a nice way to start a new year. I hope you have enjoyed this piece on Dürer’s relationship with the story of the Virgin Mary and the birth of Christ, as well as his winter errands, adventures and souvenirs. Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

– Steph

References

[1] Bridget Heal, ‘Images of the Virgin Mary and Marian devotion in Protestant Nuremberg’ in Helen Parish and William G. Naphy (editors), Religion and superstition in Reformation Europe (Manchester University Press, 2002), p. 25.

[2] Bridget Heal, ‘Images of the Virgin Mary and Marian devotion in Protestant Nuremberg’ in Helen Parish and William G. Naphy (editors), Religion and superstition in Reformation Europe (Manchester University Press, 2002), p. 29.

[3] Albrecht Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 6th January 1506 in Roger Fry (introduction) and Rudolf Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), pp. 1-2.

[4] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 6th January 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.1.

[5] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 6th January 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.1.

[6] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 6th January 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.2.

[7] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 28th February 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.4.

[8] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 8th March 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.5.

[9] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 8th March 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.6.

[10] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 18th August 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.10.

[11] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 23rd September 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.12.

[12] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 23rd September 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.13.

[13] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 18th August 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.10.

[14] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, from around the 13th October 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.14.

[15] Dürer, Letter to Wilibald Pirkheimer, 28th February 1506 in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p.5.

[16] Albrecht Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning his second stay at Antwerp (November 22-December 3, 1520) in Roger Fry (introduction) and Rudolf Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 34.

[17] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning his second stay at Antwerp (November 22-December 3, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 34.

[18] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning his second stay at Antwerp (November 22-December 3, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 34.

[19] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 34.

[20] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 35.

[21] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 35.

[22] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 35.

[23] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 35.

[24] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 36.

[25] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 3-14, 1520) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 36.

[26] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 1520- April 1521) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 36.

[27] Dürer, Passage from his diary of his a journey to the Netherlands concerning visit to Zeeland (December 1520- April 1521) in Fry (introduction) and Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009), p. 37.

Primary Sources

Roger Fry (introduction) and Rudolf Tombo (translator), Albrecht Dürer: Memoirs of Journeys to Venice and the Low Countries (London, 2009).

Further Reading

Stacey Bieler, Albrecht Dürer: Artist in the Midst of Two Storms (Eugene, 2017).

Shira Brisman, Albrecht Dürer & the Epistolary Mode of Address (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

David Eskerdijian, Albrecht Dürer: Art and Autobiography (London, 2023).

Holly Fletcher, ‘The Whitworth’s Sculpted Pietà from Renaissance Germany’, in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World (Manchester University Press, 2023), pp.121-126.

Sasha Handley and Charles Zika, ‘The Home’, in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World (Manchester University Press, 2023), pp.131-149.

Sasha Handley, Jennifer Spinks and Edward H. Wouk, ‘The Workshop’, in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World (Manchester University Press, 2023), pp.151-174.

Bridget Heal, ‘Images of the Virgin Mary and Marian devotion in Protestant Nuremberg’ in Helen Parish and William G. Naphy (editors), Religion and superstition in Reformation Europe (Manchester University Press, 2002).

Bridget Heal, The Cult of the Virgin Mary in Early Modern Germany: Protestant and Catholic Piety, 1500-1648 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Katherine Crawford Luber, Albrecht Dürer and the Venetian Renaissance (University of Cambridge Press, 2005).

Angela Hass, ‘Albrecht Dürer’s devotional images of the Virgin and Child’, Art Journal 35 June 2014, National Gallery Victoria

Heather Madar, Albrecht Dürer and the Depiction of Cultural Differences in Renaissance Europe (New York, 2023).

David Hotchkiss Price, Albrecht Dürer‘s Renaissance: Humanism, Reformation and the Art of Faith (University of Michigan Press, 2006).

Ulinka Rublack, Dürer’s Lost Masterpiece: Art and Society at the Dawn of a Global World (Oxford University Press, 2023).