Steph explores the history of pancakes and the Carnival and Shrovetide celebrations of early modern Europe.

For more information on the Art, Health and History project, click here.

For those of us who mostly observe it because we have a sweet tooth to indulge, Shrove Tuesday is better known as Pancake Day. One piece in the Whitworth’s collections always comes to mind for many a Visitor Team Assistant on Pancake Day; ‘The Pancake Woman’. Unfortunately, it’s not on display at the Whitworth at the time of writing- but that shouldn’t stop us from taking a closer look at the piece and exploring some of the celebrations that traditionally took place at this time of year in early modern Europe.

‘The Pancake Woman’ is an etching by Harmensz van Rijn Rembrandt (1606-1669), which was published in 1635. Rembrandt was a Dutch artist who was both a painter of the Baroque period and a printmaker. He produced works depicting biblical stories, mythology and historical events as well as pieces which depicted aspects of everyday life. He also produced many portraits, including self-portraits.

Rembrandt is known for the detail he paid to aspects of daily life in his drawings and etchings. We can see this attention to everyday matters in ‘The Pancake Woman’; a seated elderly woman cooks pancakes in the street. She cooks outside, selling pancakes to passers-by in need of cheap and quick food. She’s surrounded by all sorts of characters one might encounter in daily life; in the foreground a hungry little dog tries to get a reluctant child to give up their pancake, the slumped head and arms of another figure can be seen in the background as they gaze tiredly (or longingly) in the direction of the pancake woman’s pan. Two people appear to converse in the background, next to them another man leans over and looks on at the pancakes in the pan and next to him a smiling? man appears to be enjoying a pancake. Off to our left, another man seems to gaze in the direction of the pancake woman and, in front of him, perhaps held by the man, is what appears to be another hungry-looking child.

We’ve gone through the list of her potential customers but what of the pancake woman herself? Who is she? According to Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, many street vendors in early modern Europe would have been widows or elderly women who were unmarried and many poor people lacked the means to cook in rented rooms.[1] Our pancake woman likely works as a street vendor because she is in a potentially quite precarious situation- and some of her customers may largely live on a diet of food bought from vendors like her.

Now Rembrandt’s etching doesn’t depict Shrove Tuesday celebrations per se but at least some of you are here because it’s Pancake Day. So, were pancakes a ‘thing’ on Shrove Tuesday in early modern Europe? The answer appears to have been ‘yes’, although they were not the only thing consumed then. Historian Peter Burke in his book Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe notes the presence of waffles during Shrove Tuesday celebrations in the Netherlands, so we could say that pancakes weren’t always king of carbs on that particular day.[2] Pancakes vs waffles is a choice I’d struggle to make, too. The advantage to pancakes and presumably waffles, if you were on the go, was that they would have been relatively cheap and readily available from street vendors.

What was all the fuss about Shrove Tuesday and what did the celebrations entail? Shrove Tuesday itself involved a person being ‘shriven’; going to church to confess their sins and ultimately gaining absolution for them, as well as a chance for one last bout of fun. It marked the coming end of the carnival celebrations, which could begin after Christmas or even as early as the feast of St Stephen (which falls on the 26th of December, one of the Twelve Days of Christmas or Christmastide) in some territories.

For both Catholics and Protestants Shrove Tuesday is still followed by the beginning of Lent. A period that, if you were taken to church as a child, you’ll know is marked by having to give up things. Like chocolate. It was tough, wasn’t it? If you’re from a family of Catholics, you’ll know that Catholics in particular generally abstain from eating meat on Ash Wednesday, Good Friday and other Fridays during Lent. Lent in the context of late medieval and early modern Europe, like today, was a time to focus on things of a more spiritual nature and a time to go without certain things. We have started off by talking about pancakes, so let’s have a look at food during carnival celebrations and Lent in late medieval and early modern Europe.

Which foods you went without during Lent depended on where you were. Christopher Kissane notes the challenges posed by geography and its impact on availability and the price of certain foods when it came to communities having to substitute one thing for another, such as; the availability of fish and oil to substitute eggs, meat, animal fats and dairy products in settlements which were not situated along the coast and did not have olive trees.[2] Prior to the Protestant Reformation exceptions were desired from Rome and they were granted; as Kissane notes, the Nuremberg city council managed to secure dispensations which allowed the use of dairy and eggs, first granted to the poor in 1437 and later the whole city in 1476.[3]

So, if there was supposed to be a lack of dairy, meat and animal fats when it came to what people were eating during Lent, you may have guessed what people were said to be eating quite a lot of during the carnival season in late medieval and early modern Europe. The eggs and fats used to make pancakes would give them a place at the carnival table. The idea of Carnival vs Lent as opposites, one as a time of excess and the other seemingly more meagre in terms of culinary delights, is a recurring theme with historians who study food, ritual or theatre in late medieval and early modern Europe. This is certainly how some contemporaries presented the differences between Carnival and Lent during the early modern period.

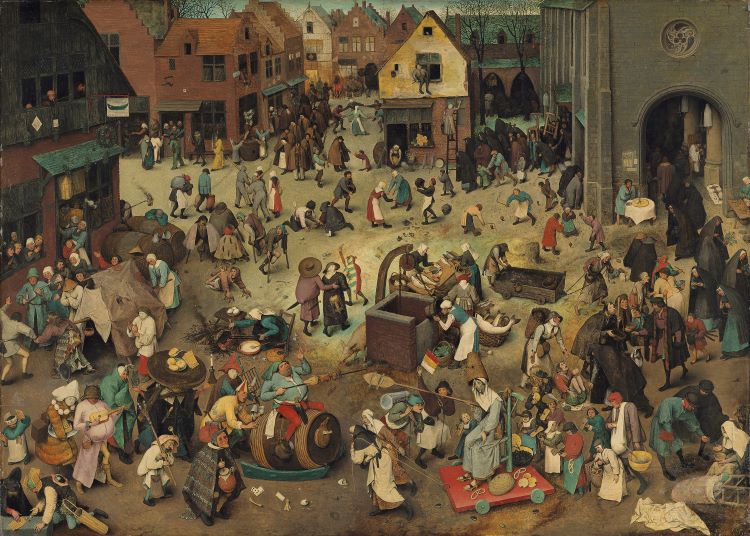

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s (1525-1569) oil painting The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559) portrays a jousting tournament between a personification of Carnival and a personification of Lent in the bottom foreground. Note the two fish on the baker’s paddle or shovel that Lent thrusts toward their adversary Carnival, whose weapon of choice is a roasting spit laden with a pig’s head and various roasted birds. People on Carnival’s side of the painting seem to be behaving in a more unruly manner, whereas Lent’s side of the painting seems more solemn at first glance. Bruegel’s painting portrays Flemish customs surrounding Carnival and Lent during the sixteenth century.

Look closer to the centre of the painting and you’ll notice a woman cooking. She has a pan on a stove, a mixture of something in a bowl at her feet and some eggs on the table next to her. At our bottom left the figure wearing a white mask and headdress carries a plate full of waffles. A man in a kneeling position in the bottom corner to our left appears to be wearing waffles on his head. The large circular table being held aloft by a nun? has waffles on it. Perhaps these waffles have been bought from the woman who is cooking near the centre of the painting? Also present on the table being carried by the person who seems to be dressed as a nun are some bread buns and what appear to be pancakes.

Carnival wasn’t just about food, though. Exactly what the celebrations entailed differed depending on where you were but it was (initially at least) generally a time of costumes, games, music and plays in many places. Look at the bottom of Bruegel’s painting, close to the figure of Carnival and you’ll see a man carrying a jug. The mouth of the jug is covered in some sort of fabric and a stick, which the man is manipulating with his hand, has been inserted through the fabric and into the jug. I suspect that the instrument is a rommelpot, an instrument which was popular in Dutch-speaking areas and would have been fairly cheap to make as it consisted of a jug containing water, an animal skin and a stick. Near the top of the painting, people appear to be dancing in the street. Close to the dancers is a man playing a set of bagpipes and leading a procession. More than just an opportunity for merriment, however, carnival festivities could also serve as an opportunity to poke fun at authorities and professions- both ecclesiastical and more secular.

If Carnival’s side of things is more unruly and contains sometimes violent imagery (note the weapons carried by a few costumed figures on our top left), Lent’s is more solemn and perhaps seen to be more compassionate; multiple people can be observed in the act of giving alms to the poor. If waffles with their eggs and animal fats are one of the foods of choice for Team Carnival, Team Lent appear to be advocating for flat bread, fish, mussels and pretzels. Behind the seated figure of Lent, a man has a pretzel which appears to be dangling from his belt and beside him a woman carries a basket containing a pretzel. Today there are different kinds of pretzels we like to snack on but food historian Regula Ysewijn notes that the Dutch word for pretzel translates to ‘crackling’, suggesting that the original pretzels were of the brittle variety- which is consistent with an avoidance of eggs and dairy products during Lent.[4] Lent’s side of the painting isn’t entirely without fun; some children are playing with spinning tops or something like them- but they aren’t smashing things like Carnival’s lot.

Just as an effigy of ‘Carnival’ or figures like Martin Luther would meet their end in mock executions in various territories throughout Europe at the close of the celebrations, attempts to reign in or put an end to aspects of carnival festivities in different territories would be made. Even before the Protestant Reformation there were those who were wary of carnival due to its apparent potential to boil over into real unrest and actual violence. The celebrations would also be scrutinised by some Catholic authorities who were concerned about the potential platform they could provide for forms of expression (such as plays) that might criticise the Church and push a pro-reform message.[5] This potential for carnival to provide an opportunity to ridicule aspects of the Church was something that some reformers, such as Martin Luther, did not oppose and even took advantage of in the early days of the Reformation.[6]

Other Protestant Reformers, such as Calvin and Zwingli, and various Protestant authorities took a dim view of carnival celebrations. Carnival didn’t disappear entirely as the 16th. century progressed. Aspects of the festivities even survived in some areas where the celebrations were largely abolished; elements of the celebrations partially endured in some Protestant territories, such as in Basel and in Nuremberg, for some time- with the festivities eventually being revived in Basel and more recently in Nuremberg. In other Protestant territories, such as Denmark and other Lutheran Scandinavian countries, Fastelavn (Shrovetide celebrations) have survived. In some Protestant territories where carnival and Shrovetide were largely done away with, fasting for Lent was also sometimes condemned. In Catholic territories, carnival tended to fare better and has survived in some places until this day.

Carnival was also exported as European powers colonised the ‘New World’. Famously, the French introduced Mardi Gras to Louisiana, with New Orleans in particular being known for its Mardi Gras celebrations. The Portuguese introduced carnival to Brazil. It was also introduced to the Caribbean as a result of colonialism. In areas colonised by Europeans, carnival celebrations would be given new customs and meaning by enslaved people who had been forcibly transported to these lands and brought their own beliefs and traditions with them.

Shrove Tuesday and some of its associated festivities seem to have held on in England throughout the centuries for better (or worse, in some cases.) A pamphlet written by one Josiah Tucker during the last half of the eighteenth century urged the people of England to desist in the sport of cock throwing or cock-shying on Shrove Tuesday. Cock throwing was a blood sport in which a rooster was tied to a post and weighted sticks were thrown at the poor creature until the inevitable happened. Tucker deemed it ‘a most unmanly and cruel diversion’ and ‘a most cruel and barbarous diversion’, which I’m sure we can all agree with. [7] [8] Tucker was also of the opinion that it was ‘offensive to God’, so for him at least there was a great deal of religious motivation for condemning cock throwing. [9]

The association of pancakes with Shrove Tuesday certainly seems to have been going strong in England during the early seventeenth century, if the scathing remarks made in a pamphlet dating back to just before the English Civil War are to be believed. A pamphlet published in 1641 entitled A Shrove-Tvesday Banquet sent to the Bishops in the Tovver sounds like a rather generous affair at first but the ‘pancakes’ given to the then Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud weren’t the edible kind. Laud had been arrested in 1640 and sent off to the Tower of London after being accused of treason by what would become known as the Long Parliament. The ‘pancakes’ he was served up with, according to the pamphlet, consisted of ‘the biting pepper of censure, the parliaments justice, the abstract of knavery, and extract of Tyrannicall Episcopacie’.[10] Still, although employed as a satirical device, the mention of these ‘pancakes’ suggest that actual pancakes were still a dish frequently associated with Shrove Tuesday.

Now back to actual pancakes. If we leave the early modern period and fast forward to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cookbooks and newspaper columns in Britain and its colonies, and in the USA, referenced the long-held association between pancakes and Shrove Tuesday. According to Everybody’s Pudding Book; or Puddings, Tarts, etc., In Their Proper Season, For All the Year Round, first published in London in 1863 and reprinted in 1887, ‘we need be in no doubt as to what we are to have for dinner- on Shrove Tuesday, golden-hued, savoury pancakes are indispensable; they have become almost an institution of our country.’[11] The publication of recipes for pancakes in books, newspaper columns, journals and magazines would continue into the twentieth century, sometimes promoting the use of an ingredient from a certain brand. A column in The Watchman, a Methodist journal published in Britain which ran from 1835-1884, included a recipe for pancakes using Borwick’s Baking Powder. The column in which the recipe was included claimed that ‘without this they cannot be well made’. [12]

I hope you have enjoyed this exploration of the customs surrounding Shrove Tuesday and Carnival in Europe during the early modern period.

There’s only one thing left to ask; what sort of pancakes will you be having today? – Steph

References

[1] Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Pres, 2019), pp. 105-106.

[2] Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (New York, 2016), pp. 255-256.

[3] Christopher Kissane, Food, Religion and Communities in Early Modern Europe (London, 2018), pp. 67-68.

[4] Regula Ysewijn, Dark Rye and Honey Cake: Festival Baking from Belgium, the Heart of the Low Countries (London, 2023), pp. 113-114.

[5] Glenn Ehrstine, Theatre, Culture and Community in Reformation Bern, 1523-1555 (Leiden, 2002), pp. 115-116.

[6] Andreas Loewe and Katherine Firth, Martin Luther and the Arts: Music, Images and Drama to Promote the Reformation (Leiden, 2022), pp.182-183.

[7] Josiah Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Common People of England Concerning Their Usual Recreations on Shrove Tuesday, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ecco-0733400200&terms=shrove%20tuesday&pageId=ecco-0733400200-20, accessed 29/01/2024]

[8] Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address, JISC Historical Texts, [7] Josiah Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Common People of England Concerning Their Usual Recreations on Shrove Tuesday, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ecco-0733400200&terms=shrove%20tuesday&pageId=ecco-0733400200-20, accessed 29/01/2024]

[9] Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address, JISC Historical Texts, [7] Josiah Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Common People of England Concerning Their Usual Recreations on Shrove Tuesday, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ecco-0733400200&terms=shrove%20tuesday&pageId=ecco-0733400200-20, accessed 29/01/2024]

[10] Anonymous, A Shrove-Tvesday Banquet sent to the Bishops in the Tovver, c.1641, JISC Historical Texts, reproduction of the original in the Thomas Collection at the British Library [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=eebo-ocm12598504e&terms=shrove%20tuesday%20banquet, accessed 29/01/2024].

[11] R. Bentley (publisher), Everybody’s Pudding Book; or Puddings, Tarts, etc., In Their Proper Season, For All the Year Round, 1887 edition, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ukmhl-b28098341&terms=pancake%20shrove%20tuesday&sort=date%2Basc&offset=60&pageId=ukmhl-b28098341-38, accessed 29/01/2024].

[12] “Multiple Classified Advertisements.” Watchman, 15 Feb. 1871, p. 56. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/HJOSZX612440015/NCCO?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=f067990c. Accessed 29 Jan. 2024.

Bibliography

University of Oxford, Early Modern Festival Books Database: https://festivals.mml.ox.ac.uk/index.php?page=list_filtered&filter=event&fvalue=5

Anonymous, A Shrove-Tvesday Banquet sent to the Bishops in the Tovver, c.1641, JISC Historical Texts, reproduction of the original in the Thomas Collection at the British Library [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=eebo-ocm12598504e&terms=shrove%20tuesday%20banquet, accessed 29/01/2024].

“Multiple Classified Advertisements.” Watchman, 15 Feb. 1871, p. 56. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/HJOSZX612440015/NCCO?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=f067990c. Accessed 29 Jan. 2024.

R. Bentley (publisher), Everybody’s Pudding Book; or Puddings, Tarts, etc., In Their Proper Season, For All the Year Round, 1887 edition, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ukmhl-b28098341&terms=pancake%20shrove%20tuesday&sort=date%2Basc&offset=60&pageId=ukmhl-b28098341-38, accessed 29/01/2024].

Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (New York, 2016).

Gordon Campbell, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Glenn Ehrstine, Theatre, Culture and Community in Reformation Bern, 1523-1555 (Leiden, 2002).

Pamela R. Franco, ‘The Invention of Traditional Mas and the Politics of Gender’, in Garth L. Green and Philip W. Scher (editors), Trinidad Carnival: The Cultural Politics of a Transnational Festival (Indiana University Press, 2007), pp. 25-47.

David Gentilcore, Food and Health in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society 1450-1800 (London, 2016).

Joyce D. Goodfriend, ‘The Struggle over the Sabbath in Petrus Stuyvesant’s New Amsterdam’x, in Wayne Ph Te Brake and Wim Klooster (editors), Power and the City in the Netherlandic World (2006), pp.205-224.

Kaspar von Greyerz (author) and Thomas Dunlap (translator), Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800 (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Emma Griffin, England’s Revelry: A History of Popular Sports and Pastimes, 1660-1830 (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Samuel Kinser, ‘Presentation and Representation: Carnival at Nuremberg, 1450-1550’, in Representations 13 (1986), pp. 1-41.

Christopher Kissane, Food, Religion and Communities in Early Modern Europe (London, 2018).

Viola König, ‘Curious Things from Mexico in Early Modern German Collections’, in Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil (editors), Collecting Mesoamerican Art Before 1940: A New World of Latin Antiquities (University of Chicago Press, 2024), pp.38-56.

Andreas Loewe and Katherine Firth, Martin Luther and the Arts: Music, Images and Drama to Promote the Reformation (Leiden, 2022).

Segiusz Michalski, The Reformation and the Visual Arts: The Protesant image question in Western and Eastern Europe (London, 2013).

Keith Moxey, Peasants, Warriors and Wives: Popular Imagery in the Reformation (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Edward Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Micahel A. Mullet, John Calvin (London, 2011).

Alexandra Onuf, ‘Secrets of the Dark: Rembrandt’s Entombment (C.1654)’, in Ralph Dekoninck, Agnès Guiderdoni and Walter S. Melion (editors), Quid est secretum? Visual Representations of Secrets in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1700 (Leiden, 2020), pp. 460-491.

Herman Pleij, ‘The Late Middle Ages and the Age of Rhetoricians, 1400-1560’, in Theo Hermans (editor), A Literary History of the Low Countries (New York, 2009), pp. 63-152.

Klaus Ridder, Beatrice von Lüpke and Rebecca Nekker, ‘From Festival to Revolt. Carnival Theatre during the Late Middle Ages and Early Reformation as a Threat to Social Order’, in Cora Dietl, Christoph Schanze and Glenn Erhstine (editors), Power and Violence in Medieval and Early Modern Theatre (V & R unipress, 2014), pp. 153-168.

Julius R. Ruff, Violence in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800 (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Barry Stephenson, ‘Ritual Negotiations in Lutherland’, in Ute Hüsken and Frank Neubert (editors), Negotiating Rites (Oxford, 2012), pp.81-98.

Josiah Tucker, An Earnest and Affectionate Address to the Common People of England Concerning Their Usual Recreations on Shrove Tuesday, JISC Historical Texts [https://data-historicaltexts-jisc-ac-uk.manchester.idm.oclc.org/view?pubId=ecco-0733400200&terms=shrove%20tuesday&pageId=ecco-0733400200-20, accessed 29/01/2024].

Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Pres, 2019).

Regula Ysewijn, Dark Rye and Honey Cake: Festival Baking from Belgium, the Heart of the Low Countries (London, 2023).