From looking to traditional skills to create a sustainable future to exploring how technology can create and recreate an experience of textiles in a digital space, Debra walks us through the ideas exchanged at the Textile and Place Conference in Manchester, 2023.

The Textile and Place Conference 2023 at Manchester School of Art in partnership with the British Textile Biennial 2023 engaged with the social, environmental, and historical legacies of textiles with its associated global connections as well as modern technological advances that push the medium of textiles into new areas of cutting-edge research and relevance.

Part 1 of the Conference

Regenerative acts ‘How can we learn from our traditions to reimagine our futures’?

Textiles have a unique way of connecting us to place and spaces we inhabit, including digital and virtual spaces and have embedded within them a complex range of symbolism, meaning, identity and narrative.

There is a ‘continuous lifecycle’ within textiles unlike other materials, and they can play a spiritual and ceremonial role in our lives because they are central to the lived human experience. Because of their material nature the process of touch, as well as the visual experience of them, is integral to how we experience their qualities and our relationship to them.

In the North West our landscape is marked by industrial history; the industrial revolution changed our connection to places and spaces. Previously textiles made in this region were indigenous to the land, using wool from sheep and linen made from flax. People who spun and wove the cloth worked in harmony with nature and had an instinctive knowledge of plants and the soil, through fibre, threads, colours, spinning, weaving, and dyeing. We lived adapting to the changes of the seasons, climate, nature, and environment.

Mass industrial production has taken us away from our connection to the land and changed our relationship to the world, and material culture, because of this. There is an urgent need to try to reconnect with the relationships we once had to land and place because of the devastating impact climate change is having to our planet. This is especially important because of the damage the textile and fashion industry contribute toward climate change, through pollution and carbon emissions.

The cotton industry that developed in this region due to global trade, colonial expansion and the transatlantic slave trade changed the way our culture made textiles. The cotton industry meant that we no longer made cloth from a material that was grown here and instead relied on a system of human trafficking and slavery as part of its production.

Industrialisation was a benefit to the economy in Britain while we were the leader in producing textiles to global markets but was a burden to the environment and socially for those who laboured in the mills, mines, and factories. Since the decline in our prominence with manufacturing, this has had an impact on diverse communities in different ways, including economically as the industrial landscape has changed.

The Textile Biennial 2023 in Pennine Lancashire looked at these different threads, and complex histories. It explored how trade, diasporic communities, migration, and exploitative nostalgic narratives are embedded and reframed. It also examined how fast fashion is having a devastating impact on the planet and uses the same trade routes that once built the textile history here. The ways in which our relationships to textiles have changed through mechanisation and post-industrial decline were also explored, as were the ways in which craft knowledge and artisan cultures globally were affected by colonialism. So, are we able to learn from the past and different indigenous craft traditions for a more sustainable future?

Christine Checinska is Senior Curator of Africa and Diaspora: Textiles and Fashion, and Lead Curator of Africa Fashion at the V&A Museum. In her keynote speech and in her research work more broadly she explores the connections between cloth, culture, and race. Checinska asks what can textiles do that science and words cannot.

Cloth can be a symbol of cultural heritage that often becomes hybridized over time with the culture of a new place. Diasporic communities bring their own stories of migration and textile practices, which are then often ‘creolised’ into the textile practices of the new culture. Checinska referenced Althea McNish, whose trailblazing design legacy we recently exhibited at The Whitworth in 2022-2023. McNish was the first Caribbean born designer to reach international design success. Her design work set trends and contributed to the modernist aesthetic that innovated post war design in the late 50’s onwards. She introduced a different and distinctive visual language to people’s homes and fashion style. With her instinctive and confident use of vibrant colour and tactile pattern she merged influences from her upbringing in Trinidad with British flora and fine art influences.

Currently displayed in Gallery 1 Exchanges Exhibition 2023 -2024. Photo by Debra Boothroyd

What is often missing from design discussions and narratives are the voices, and creative practices of Black designers and those from the Global South. Checinska noted that for a long time there was a belief that Africa had no ‘art forms’, and their material culture was instead confined to museums as ethnographic objects. This misrepresentation is only recently being transformed in all aspects of approaches to the representation and presentation of African textiles from a historical and contemporary context.

Checinska is the first curator at the V & A that specialises in African textile and fashion design, and she is a champion of contemporary Pan-African fashion and textile designers, and those of African descent who are the forefront of their craft. The independence of African nations in the mid 20th century allowed a flourishing of creativity in textiles and fashion and a ‘cultural renaissance’ using traditions of making practices, local craft processes, techniques, cloth, and textiles. In recent years, there has also been a determined rejection of the Global North’s need to mass produce designs and trends at a high turnover- which is having a major impact on the environment globally.

Contemporary African designers are passionate about having a strong focus on sustainability and social responsibility as part of their practice. African nations receive millions of tons of imported second-hand clothing from the Global North, which is a major environmental issue as much ends up in landfill or is incinerated due to being very poor quality- meaning it cannot be resold or reused. The import of these clothes also impacts the local textile industries, due to their low cost, and the European designs impact the local economy and local production of textiles.

Bubo Ogisi is a fashion Designer from Lagos who focuses on the material quality of textiles and working in a sustainable way; craft and artisan process are integral to her work. She explores identity and the spiritual qualities of textiles and seeks to decolonize through her work. She produces exquisite fabrics, mixing traditional techniques with the new to create a contemporary reimagining of heritage. Ogisi works with local artisan communities from different parts of Africa to make her ‘slow’ fashion, where every piece is mostly made by hand.

IAMISIGO: THE BRAND WHOSE CONCEPTUAL FASHION TAPS INTO AFRICAN HISTORY – Industrie Africa

Awa Meite from Mali also puts sustainable practice at the heart at what she does using traditional indigenous textile techniques, with handwoven, printed, and natural dyed cotton textiles made from cotton grown locally. Mali produces the most cotton in Africa, so it is an important resource for the local economy. Her practice focuses on socially responsible designs and practices, by challenging the Global North’s and Fast Fashion’s over consumption models. Globally the fashion industry is 2nd behind the oil industry as the biggest polluters on the planet.

Awa Meité — IA Connect | Industrie Africa

Sustainable Culture and Heritage

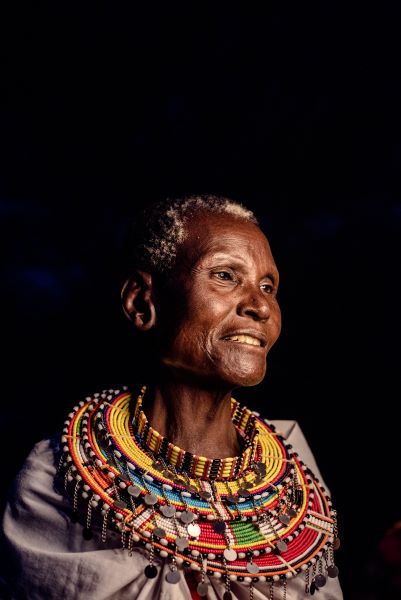

Artist Naitiemu Nyanjom is a material and performance artist and artistic director, she developed Enkang ang ‘an artistic exploration of female Maasai culture and heritage, as matriarchal Leaders, healers, and warriors.

Enkang’ Ang’ (In Maasai : ‘Our Home’) | Naitiemu

Colonialism can, in many ways, change the way different indigenous cultures make a textile, through loss of communities, ancestral practices, skills, knowledge, plants (which are used as dyes or yarn), tools and textile machines (such as looms) to make the textiles. Woven, embroidered and print patterns can disappear or change and evolve.

Maasai heritage is a semi -nomadic culture, and the Maasai are one of the few tribes remaining in Africa that have kept hold of most of their traditions and way of life post-colonialism. Climate change is also having an impact on how they can go about their traditions and is one of the biggest issues they face. They have looked at ways to adapt to these changes while still holding on to the essence of their culture and craft by still focusing on a sustainable way of living with nature and materials. For example, they use permaculture methods with the local plant aloe vera which is important in the semi-arid climate (which is more vulnerable to drought), as growing the plant reduces soil erosion and it can be made into different products to be sold, including honey from the flowers.

There is an important integration of all aspects to their heritage culture

The colours that are represented in the textiles and jewellery represent their way of life and traditions. Red – strength and unity – represents the blood of cows which are slaughtered for celebrations Blue -Sky/ water, Yellow – fertility sun, Green – land and nature, Black – protection, White – like cow’s milk – purity and energy.

Enkang’ Ang’, ‘Enkayukoni’ contemporises Maasi heritage through performance art.

Maasai people wrap themselves with a plaid patterned cloth called ‘Shuka’, which is dominated by the colour red. This type of fabric design was perhaps adopted into their culture when the region was colonised by Scottish missionaries during the 19th century. They wear beaded jewellery around the neck and wrists, which represents their age and social status. These items of jewellery are now made from materials imported from Europe (glass and plastic beads). Originally these would have been made from stones, bone and seeds, and shells traded locally. Leather is also a valuable resource from the cattle they nurture, and these animals are central to their pastoral way of life; they are used as food, ceremonial items and clothing. Leather is also used as a textile base for the jewellery they craft.

Colonialism and globalisation can disrupt identity, culture and links with the past but traditional ways can be reimagined and adapted, heritage can be reclaimed, and cultural artefacts can be modernised as part of this adaption, so a sense of one’s own identity is not lost.

What is tradition, who defines and who sets the narrative?

The idea and meaning of place and the social fabric of space is very malleable and can be reimagined. But what is authentic and what is true? Historically, cultural memory can be a narrative constructed and reconstructed and there can also be ambiguity.

Sam Meech is an artist, educator, and video smith from Huddersfield (UK), whose practice combines projection design, interactive video installation, community engagement, and digital textiles.

He has documented the impact of gentrification in Manchester on working class communities with his textile work. Several South Asian knitting companies were originally based in Crusader Mill, one of the last historical industrial buildings in the city. These companies had been there for decades, and the mill also housed artist studios Rogue where Sam was based. Sam worked collaboratively with the companies Unique Knitwear and Imperial Knitwear to document their fate and that of the other companies faced with eviction in 2015. He uses a knitted textile production which is a hybrid process of digital and analogue. His work was an attempt to challenge the narrative from the developers, who were erasing their existence and significance to Manchester’s industrial textile history. His work shows that the cultural memory and heritage of a place can be reconstructed and represented as authentic by those who wish to capitalise on a selective version of history for commercial purposes.

The layers of paint on the walls of the mill revealed a history of past and present. Meech captured this history in square shaped knitted samples. These digital patterns acted as an archive of what became lost and erased during redevelopment of the mill. Meech produced several projects which used knitting, animation and film media as an important ‘counter narrative’.

http://portfolio.smeech.co.uk/fabrications/

Knitted tile placed over the original painted wall in Crusader Mill. 40cm squares capture and act as an archive to what will become lost to redevelopment. Using a digital pattern that blend with the walls. Fait Accompli, Sam Meech 2016

Part 2 of the Conference

Time, Space and Non-places: discussing textile as future orientated and how materiality can be experienced through digital and virtual realms.

Interesting theoretical and conceptual ideas were explored with a keynote speech by Dr Elaine Igoe, a leading academic on textile design theory and practice. A research project by academic and designer Elaine Bonavia (Syntopia) works in computational design, art and technology and argues the existence of tacit knowledge and the sensory experiences of digital textiles and craft bring us into the future of where textiles can go

Much of our lives are lived through a virtual screen, and through a digital lens, new technology can be utilized to understand our connection and our tacit knowledge of making and textiles, place, and spaces. Creating designs and using data, by exploring the haptic and creating and constructing prototypes in spaces and places, still needs elements of human processes and interactions.

When realising futures through hyper modern materials using AI and augmented reality, there is still a need for material knowledge and a sense of craft. Technology can be used as a tool and support processes in new ways of thinking and learning and in different forms of making.

Exploring what is possible is a journey of discovery through experimentation and multi-disciplinary and transdisciplinary collaboration. Technology and innovation have always been part of making, but what is tradition? And what is innovation? Makers have always explored new ways and methods of making throughout history.

It made me think about the exhibition Albrecht Dürer’s Material World currently on display at the Whitworth, which explores the impact of global trade and luxury artisan culture in 15th century Nuremberg; adjacent to the technology of the printing press and the influence this had on the creative life of Albrecht Dürer. He developed new art forms for the time, innovated and pushed their potential by using different craft orientated techniques and the modern technology of the day. Collaboration in workshops across Europe drove innovation through different artisan skills and a transference of knowledge and ideas.

The Fourth Knot c 1506 – 8, Woodcut. Albrecht Dürer’s Interlaced knot designs, inspired by Leonardo de Vinci, were decorative designs which were popular as textile and embroidery patterns in renaissance Italy. Durer’s experience as a goldsmith must have drawn him to the complex patterns; combined with his philosophical perspectives and observations on nature and the links with the meaning of art and the mind and creative cognition. These patterns are meditative and complex and would have required amazing manual skill to create. Accession number: P.3056.

There is also a continuation and evolution of the Renaissance idea and metaphor of the ‘virtual’ as a space (a picture as a window) through the philosophical writings of Leon Battista Alberti- whose treatise on the laws of linear perspective, De pictura (c.1435), Durer was influenced by in his later work after 1510. These ideas are explored in depth by Anna Friedberg in her book on the virtual window (2006).

A window, a frame around an artwork, a digital view, a computer screen, and the rectangular shape of a textile sample or swatch, work as a single frame for multiple views and perspectives which transverse perception of time, space, and place, the temporal, the material and immaterial reality.

Green-blue silk-linen fragment, Late 16th century or early 17th century Italian, Albrecht Dürer’s Material World exhibition 2023 – 2024 . This is fragment of a textile which was originally part of a wrapper for a religious relic. Here a repeating pattern which runs off the edge of the swatch is in fact ‘infinite and rhythmic’. Accession number: T.12630

Different design eras have all had elements of craft and innovation. Modernism in the 20th century combined some elements of craft but was also about designing for a new world, with a utopian social vision and a different way of living, by using the modern technology of industrial production with materials like steel, glass, concrete, and plastics.

In the early 2000s biology and technology combined, and there was a movement of hypermodernity (super modernity) where the ‘form follows function’ of Modernism became an inversion of itself. Biology, biotechnology, and bio – materials were explored and became a trend and material aesthetic within textile design. The focus was on designing for a new millennium, which was very future orientated, with a need to create more sustainable, regenerative textiles and materials that took inspiration from nature; ‘bio mimicry’.

Driven by 21st century technology, and hyper-individualism we are now living in an era where the line has become even more blurred between what is real and unreal. Designers are creating new immersive experiences of materiality and looking to the future of new possibilities in a post-digital world.

Netherlands based Designer and Academic Angella Mackay ‘investigates wearable technologies’- Phem, (2019) Digital Fashion using Augmented Reality, where there is a hybridity between the digital and reality creating immersive and responsive textures which are dynamic with a feminine aesthetic and ‘ephemeral experience’ creating a digital experience that is more ‘real’, taking essences from digital experiences such as light and shimmer into the real world.

Designers and researchers are using AI, digital spaces, 3D printing, computational design, augmented reality and the metaverse. Platforms where the digital can recreate tangible objects which are designed to be experienced in a virtual space.

Data can be collected through the making process using augmented gloves, data can be visualised as a framework, like a network, and patterns can be woven to understand matter and space and create prototypes for site specific spaces and architecture that can be adaptive. Design is becoming a conceptual practice, where examining the essence of materials can be used to explore different forms of materiality for design purposes and creating a different aesthetic language.

What is apparent is a need, still, of material knowledge and cognitive creativity to create virtual representations and renderings which have some element of authenticity in the digital realm. There has always been an understanding of the need to have experience and knowledge of materials and their properties to design effectively. Augmented reality can support the process of creating, but there is still a need for tacit knowledge and haptic knowledge. The materiality of craft is being explored in the digital creating hyper-realistic, immersive textures and forms. Digital has its own material language but it also has the potential to be as real as reality. Pioneers of this direction in are Lucy Hardcastle, based in London, and Zietguised, based in Berlin, who understand the importance of craft within their work and experiment with the aesthetic qualities and textures of digital realism.

Crafting Futures – Rethinking what is craft what is possible.

Interdisciplinary methods and research can develop new forms of making, design aesthetics, materials and visual language.

Craft skills have always been fundamental to progress in design and making; some designers in the past chose to reject working in new ways and focused purely on ‘traditional’ skills, like William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. But a rejection of modernity can also lead to a lack of innovation and progress in adapting to change. Change is an inevitable and unavoidable part of the human experience.

Craft has always evolved to use new technology in a supportive role, to create and innovate. Now there is digital craft, creating new forms of craft in digital spaces, by rethinking what craft is. Do we always need material objects? With the possibilities of digital, reality can be blurred, and the experience of an object can be created and recreated. Digitised textiles can be rendered in hyper-real qualities to experience their materiality for different purposes. This type of technology could be used by museums and galleries to make something accessible virtually, such as a heritage textile that is now lost or too fragile for public display. It is currently being adopted for commercial reasons in the textile industry for trade and marketing, which could be used as a more sustainable element to an industry which creates a lot of waste.

Creativity can be pushed in many ways to explore diverse ways of thinking incorporating some technology present at that moment. These new ways of working can help us adapt and face different challenges.

A selection of further reading and designers

How fast fashion is fuelling the fashion waste crisis in Africa – Greenpeace Africa

http://portfolio.smeech.co.uk/fabrications/

https://phem.design/photo-gallery

Anna Freidberg, The Virtual Window, From Alberti to Microsoft, Publisher: The MIT Press

Hanß, Stefan. ‘The nature of lines: enviromateriality and ingenuity in Albrecht Dürer’s material world’. In Albrecht Dürer’s material world, edited by Edward H. Wouk and Jennifer Spinks, 49-61. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023.

Elaine Igoe, ‘Where Surface Meets Depth: Virtuality in Textile and Material Design’