Read about lesser celandine, an often overlooked herald of spring, and the ways in which it has been used in decorative designs, literature and medicine in this post by Steph.

For more information on the Art, Health and History project, click here.

As you walk toward our Oxford Road entrance between the months of January and April (and sometimes even into May), you may be greeted by tiny, golden star-like flowers. These are lesser celandine or Ficaria verna. One of the first flowers to emerge after winter, they are often seen as a sign of the coming of spring. Lesser celandine petals have the same glossy appearance as creeping buttercups and meadow buttercups, which is not surprising as the plant is a member of the buttercup family. However, lesser celandine flowers have more petals than some of their relatives, usually numbering about eight to twelve petals in total. There is another species which is referred to as celandine, greater celandine (Chelidonium majus), which is not related and is instead a member of the poppy family. Greater celandine tends to bloom later in the year from April to October.

The flowers may shine beautifully but lesser celandine can often be found in the shade. You can spot it in ditches and hedgerows in addition to damp woodland areas, where it sometimes creates spectacular carpets studded with brilliant little star-like booms, and by the banks of streams. It can also be found in meadows and in some gardens.

Despite its preference for damp soil, the flowers of lesser celandine shy away from rain and will close up on rainy days. Once the sun is shining again, they unfurl their petals.

Our lesser celandine is in full bloom as a write this. Each year, I eagerly await the blooming of these flowers just as much as I look forward to the blooming of cherry blossoms. Let’s have a look at some of the decorative, literary and past medicinal associations and uses of a plant many now seem to overlook in favour of other plants associated with spring.

Lesser Celandine in Literature

The image of lesser celandine as a symbol of spring has earned it a reputation as a herald of brighter days and hope. This symbolism has been utilised by some of Britain’s best-loved authors.

In his novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe C. S. Lewis wrote a description of flowers, including lesser celandine, blooming as winter receded:

‘Soon there were more wonderful things happening. Coming suddenly round a corner into a glade of silver birch trees Edmund saw the ground covered in all directions with little yellow flowers- celandines. ‘ – C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Chapter 11. [1]

The appearance of lesser celandine and other flora associated with the coming of spring was used as a sign to indicate that Aslan had returned to Narnia.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a friend of C. S. Lewis, described his character Glorfindel as wearing a mantel ‘so broidered in threads of gold that it was diapered with celandine as a field in spring‘ into battle at the Fall of Gondolin in The Book of Lost Tales, Part II. [2] In Tolkien’s Middle Earth, the elf Glorfindel was the Lord of the House of the Golden Flower in the hidden city of Gondolin. In the accounts of the Fall of Gondolin in The Silmarillion and The Book of Lost Tales, Glorfindel died fighting a Balrog in order to allow refugees from the city to escape. The character also appears briefly in The Lord of the Rings. In The Fellowship of the Ring he was sent to search for Frodo and his companions and escorts them to Rivendell. Glorfindel’s power caused the Nazgûl to flee from him. His rescue of Frodo and his companions after their encounter with the Ringwraiths is absent from both Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 animated film The Lord of the Rings (which only adapted events from The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers) and Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

The events described in The Silmarillion and The Book of Lost Tales take place long before The Lord of the Rings. At some point Tolkien seems to have decided that the Glorfindel described in The Lord of the Rings would be the same character as the Glorfindel who appears in stories which are set ages before the events of The Lord of the Rings– meaning that Glorfindel would have been re-embodied after his battle with the Balrog. So, Aslan isn’t the only literary character who is associated with celandine and eventually returns to life.

In addition to classic fantasy novels by two of Britain’s greatest authors, lesser celandine has also appeared in poems produced by one of Britain’s best-loved poets. Daffodils were not, as some may assume, William Wordsworth’s favourite flower. He preferred lesser celandine and, although his poem I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud is perhaps better known to most, he penned poems celebrating lesser celandine as well, which were entitled To the Small Celandine and To the Same Flower. In both poems he praised lesser celandine as a herald of spring and expressed joy at spotting its flowers. Both poems give the impression that Wordsworth considered the flower to be underrated.

In To the Small Celandine he wrote:

‘Buttercups, that will be see,

Whether we will see on no;

Others, too, of lofty mien;

They have done as worldlings do,

Taken praise that should be thine

Little, humble celandine!’ [3]

And in To the Same Flower:

‘Praise it be enough for me,

If there be but three of four,

Who will love my little flower’ [4]

Wall Flowers

Celandine flowers decorate the memorial plaque dedicated to Wordsworth at Grasmere’s Church of St Oswald, which was installed around 1850, but they are greater celandine flowers. The inclusion of greater celandine on the plaque seems to have been an unfortunate mistake.[5]

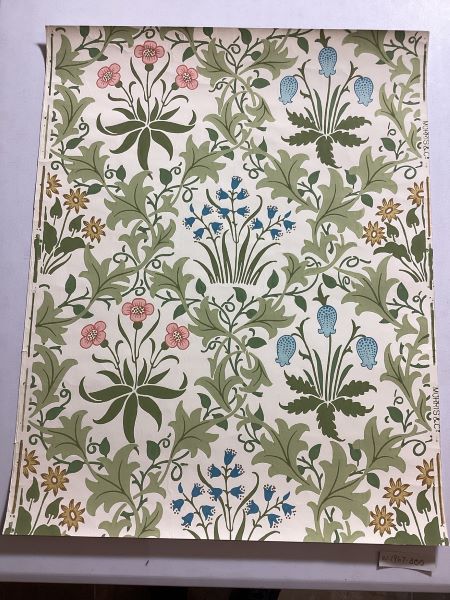

Lesser celandine may not grace a monument to a poet who perhaps considered himself one of its biggest fans, but John Henry Dearle saw fit to include it in a wallpaper design- which also bears the name ‘Celandine’. The wallpaper also bears the name of Morris & Co, for whom it was manufactured. Dearle’s career at Morris & Co had started off with him working at the company’s Oxford Street shop. He was later selected by William Morris to be a tapestry apprentice and he eventually became the principal designer for Morris & Co after Morris died in 1896.

You’ll have no doubt noticed that, much like real lesser celandine, the lesser celandine on this wallpaper seems to be relegated to the shade. I’m not quite sure why that is but for me the lesser celandine and what I think are supposed to be stylised bluebells are some of the best features of the design. As lovely as daffodils are, for me bluebells and lesser celandine are two of our most beautiful native spring blooms.

Historic Medicinal Uses of Lesser Celandine

It’s not generally a good idea to eat members of the buttercup family. However, the heart-shaped leaves of lesser celandine are supposed to contain high levels of vitamin C and have been used sparingly in salads. The plant does contain toxins, though, and I believe the leaves are usually cooked to make them safer to consume.

Everything we have covered so far paints lesser celandine in a rather beautiful light. Unfortunately, the ways in which it was utilised in some medicinal remedies were not so glamorous. Lesser celandine is also known as pilewort- which gives you a good idea as to what it was sometimes employed as a remedy for in early modern England.

Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654 CE) included lesser celandine or pilewort in his The English Physician, which later became known as The Complete Herbal during the nineteenth century. Of the plant, he had this to say:

‘It is under the dominion of Mars, and behold here another verification of the learning of the ancients…that the virtue of an herb may be known by its signature; for if you dig up the root of it, you shall perceive the perfect image of the disease they commonly call the piles’- Nicholas Culpeper, in Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (New York, 2019), edited by Steven Foster and based on the 1653 second edition of The English Physician with additions from an edition published in 1850. [6]

In other words, because people thought the root tubers of lesser celandine looked a bit like a haemorrhoids they thought it would be an effective remedy against the ailment.

Culpeper also considered lesser celandine to be a useful remedy for other medical issues:

‘…kernels by the ears and throat, called the king’s evil, or any other hard wens or tumours’. – Nicholas Culpeper. [7]

The ‘king’s evil’ was a term applied to scrofula, which is an infection in the lymph nodes in the neck. It would cause the lymph nodes to swell up, which likely explains the ‘kernels’ Culpeper listed in his entry on the uses of lesser celandine. If you have never heard of scrofula before and are wondering why that is the case, it’s likely because the bacteria which causes tuberculosis is the most common cause of scrofula. Tuberculosis is no longer seen in Britain as often as it was in centuries past thanks to vaccination efforts during the twentieth century. Don’t get too complacent, though; TB has never really gone away, with some countries still having a high incidence of TB. Although Britain on the whole has a low-incidence of TB, cases rose slightly in England in 2023.

As for how pilewort was to be administered, Culpeper claimed it was effective when ‘made into an oil, ointment or plaster’. He went on to say ‘…borne about one’s body next to the skin helps in such diseases, though it never touched the place grieved…with this I cured my own daughter of the king’s evil, broke the sore, drew out a quarter of a pint of corruption…’ [8] To me, it sounds like Culpeper was describing using the lesser celandine as a topical treatment and then bleeding the swollen lymph nodes. Bleeding a patient was a treatment commonly recommended and used when the Theory of the Four Humors was still influential on medicine in Europe. Purging was another common treatment, which could be induced by remedies containing certain plants- some of which we wouldn’t ingest today because of their toxicity to humans. For more on this and the Theory of the Four Humors more generally, see my post about the history of hellebore. If you would like to learn about some of the history and traditions surrounding other spring flowers, see my posts on cherry blossoms and hawthorn.

Although astringent and other potentially useful properties have been attributed to lesser celandine, don’t be too eager to try using it as a medicinal remedy yourself. A study published in 2015 suggested that the case of a woman suffering from hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) may have occurred due to the lesser celandine extract she was consuming as tea.[9] According to the study, other possible causes were considered and ruled out and, following the discontinuation of the lesser celandine extract, the patient’s condition apparently improved.[10]

The medicinal uses of lesser celandine in centuries past may not sound appealing but lesser celandine does benefit other species, as the flowers serve as a crucial source of nectar for queen bumblebees and other pollinators which emerge early on in the year. In providing food for pollinators, who in turn help to provide food for us, lesser celandine ultimately benefits us too. So remember to look down on your next spring walk, even in ditches. You may spot some bright little flowers.

References

[1] C. S Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe first published in 1950 (this edition London, 2009), Chapter 11.

[2] J. R. R. Tolkien (author) and Christopher Tolkien (editor), The Book of Lost Tales, Part II, published posthumously, first published 1983 (this edition London, 1992), Chapter 3

[3] William Wordsworth, ‘To the Small Celandine’ [accessed online at http://www.logoslibrary.org/wordsworth/small.html]

[4] William Wordsworth, ‘To the Same Flower’ [accessed online at http://www.logoslibrary.org/wordsworth/small.html]

[5] Alan Bewell, Natures in Translation: Romanticism and Colonial Natural History (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), pp. 85-86.

[6] Nicholas Culpeper and Steven Foster (editor), in Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (New York, 2019), pp.48-49.

[7] Culpeper (author) and Foster (editor), in Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (New York, 2019), p.49.

[8] Culpeper (author) and Foster (editor), in Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (New York, 2019), p.49.

[9] Bulent Yilmaz, Bariş Yilmaz, Bora Aktaş, Ozan Unlu and Emir Charles Roach, ‘Lesser celandine (pilewort) induced acute toxic liver injury: The first case report worldwide’, in World J Hepatol 7 (2), Feb 27 (2015), accessed online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4342611/

[10] Yilmaz, Yilmaz, Aktaş, Unlu and Roach, ‘Lesser celandine (pilewort) induced acute toxic liver injury: The first case report worldwide’, in World J Hepatol 7 (2), Feb 27 (2015), accessed online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4342611/

Bibliography

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tuberculosis-tb-cases-continue-to-rise-in-england-in-2023

Mary Ellen Bellanca, ‘Jane Loudon’s wildflowers, popular science, and the Victorian culture of knowledge’, in Lawrence W. Mazzeno and Ronald D. Morrison (editors), Victorian Writers and the Environment (London, 2017), pp.174-187.

Alan Bewell, Natures in Translation: Romanticism and Colonial Natural History (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017).

Nicholas Culpeper (author) and Steven Foster (editor), in Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (New York, 2019).

Charles Harvey and Jon Press, William Morris: Design and Enterprise in Victorian Britain (Manchester University Press, 1991).

Rebecca J. Keyel, ‘Morris & Co’ in Monica Penick and Christopher Long (editors), The Rise of Everyday Design: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain and America (Yale University Press, 2019), pp.51-62.

C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe first published in 1950 (this edition London, 2009).

J. W. Mackail, The Life of William Morris (New York, 2013).

Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (The University of Virginia Press, 2012).

J. R. R. Tolkien (author) and Christopher Tolkien (editor), The Book of Lost Tales, Vol II. published posthumously, first published 1983 (this edition London, 1992).

Bulent Yilmaz, Bariş Yilmaz, Bora Aktaş, Ozan Unlu and Emir Charles Roach, ‘Lesser celandine (pilewort) induced acute toxic liver injury: The first case report worldwide’, in World J Hepatol 7 (2), Feb 27 (2015), accessed online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4342611/

William Wordsworth, ‘To the Small Celandine’, [accessed online at http://www.logoslibrary.org/wordsworth/small.html]

William Wordsworth, ‘To the Same Flower’, [accessed online at http://www.logoslibrary.org/wordsworth/small.html]

Saeko Yoshikawa, William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820-1900 (New York, 2016).

Great and informative post on a flower I’ve probably seen but never known about. A beautiful wallpaper, as you’d expect from Morris & Co, but I think I’ll give Culpepper a miss…..

LikeLiked by 1 person