In Part One of Steph’s Exploring the Floating World series, we get a crash course in Japanese history from the Sengoku Jidai to the Edo Period and we start to learn about the emergence of the ukiyo-e genre.

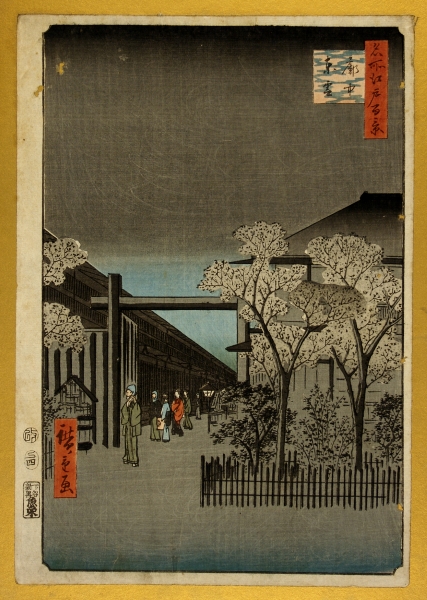

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which emerged during the Edo period (1603-1868, also known as the Tokugawa period). The genre took its name from the the concept of a ‘floating world’, in which nothing is permanent. Although this concept ultimately derives from Buddhist beliefs about the transient nature of life, the people of Edo had their own rather cheeky and hedonistic version of a ‘floating world’ in which one could enjoy fleeting encounters and pleasures, the Yoshiwara district. This was the entertainment or pleasure district of Edo (now Tokyo) and, as you may have already guessed, it did contain (legal) brothels. Tea houses, restaurants and kabuki theatres could also be found there. The term ‘ukiyo-e’ is most often applied to woodblock prints, however the artists who designed such prints also produced beautiful paintings.

In this first instalment of Exploring the Floating World, we will be learning about the history of Japan leading up to and into the Edo period and look at some of the various developments which set the stage for the emergence of the ukiyo-e genre.

The Sengoku Jidai

In order to understand the world ukiyo-e emerged into and how it was structured, we need to know a little bit about the Edo period and what came before it- so here’s a very simplified (perhaps overly so) overview. Prior to the Edo period, Japan was a series of smaller territories locked in wars and skirmishes during the Sengoku Jidai (1467-1615 CE) or period of warring states, part of which overlapped with the Muromachi period (1338-1573 CE). The Muromachi period was named for a district located in Kyōto, where the Ashikaga shogunate had established their administrative headquarters. The Sengoku Jidai took its name (as you may have guessed) from the amount of conflict which occurred during this period, which contemporaries likened to the warring states period of ancient China. It’s important to note that there appears to be some debate among historians as to when the Sengoku Jidai actually began.

During the beginning of the Sengoku Jidai, the emperor was something of a spiritual figurehead and the shōgun (basically a military dictator, this was a hereditary post held by whoever became the head of whatever warrior clan was in charge) was, in theory, supposed to run things on his behalf- although they too could end up being more of a figurehead. The Ōnin War (1467-1477 CE), which occurred roughly around the start of the Sengoku Jidai, broke out due to a dispute between the kanrei (a high official/ shōgun’s deputy) Hosokawa Katsumoto and his father-in-law Yamana Sōzen (a daimyo). Both were allied with other warrior clans, and they fought over which member of the Ashikaga clan should become the next shōgun. The fighting, which broke out around Kyōto, then led to conflicts in other parts of Japan as the power of the shogunate grew weaker. ‘Shogunate’ is a term more commonly used in English for the bakufu, the military government with a shōgun at the top.

As the Sengoku Jidai progressed, various regional feudal lords or daimyo vied for control of more territory. Some daimyo became powerful enough to try to gain control of the shōgun from other rival warlords.[1] One such warlord was Oda Nobunaga (1534-82 CE), who dissolved the shogunate in 1573. He was the first of three great warlords whose actions led to the unification of Japan. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536/7-1598 CE), who had risen from humble beginnings (he was the son of a peasant) to eventually become a daimyo in the service of Oda Nobunaga, succeeded his master and led campaigns to bring more of Japan under his control. Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616 CE) was the last of the three. He established himself as the next shōgun after having served under Oda Nobunaga and later his rival for power, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. His newly established bakufu (1603-1867 CE) became Japan’s last.

Edo Period Foreign Policy

The Tokugawa or Edo period (named after the place where Tokugawa Ieyasu established his headquarters as shōgun, now known as Tokyo) spanned from around 1603-1868 CE. As with the Sengoku Jidai, some people use different start dates for the Edo period. It was a relatively peaceful period for Japan, especially in comparison to the Sengoku Jidai. However, there were also many restrictions brought into place by the Tokugawa shogunate and there were other, pre-existing restrictions which had been initiated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The restrictions brought in by the Tokugawa were often designed to reinforce their power and control over Japan by trying to prevent the spread of ideas they viewed as a potential threat to their power or to crackdown on things which were deemed immoral. What are now commonly referred to as the sakoku, edicts which enforced Japan’s perceived isolation, were passed during the early 17th century. The last of these edicts was passed in 1639 when the Portuguese were forbidden from trading with Japan. The sakoku edicts forbade the Japanese from travelling outside of Japan, tried to restrict the spread of Christianity in Japan and also aimed to control the flow and distribution of various foreign goods (and ideas via books) coming into Japan.[2] [3]

The Edo period was not one of immediate or absolute isolation, it was one of restrictions- some of which would later be relaxed and allow for a greater spread of European ideas in Japan. The Dutch could still trade with Japan at Dejima, an artificial island built in Nagasaki harbour which was used as a trading post. There had also been some contact with the English, largely via the English East India Company. William Adams, often referred to as ‘the first Englishman in Japan’, was given a position as a retainer to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Adams lived out the rest of his life in Japan after the Dutch ship he had served on as chief pilot was wrecked, leaving him marooned in 1600 and forbidden from returning home. He was given the name Miura Anjin by Tokugawa Ieyasu. Adams encouraged Dutch and English traders to travel to Japan and establish ‘factories’ there.[4] The character of John Blackthorne in the novel Shōgun by James Clavell and the 2024 drama series on Disney Plus, which is based on the novel, is apparently loosely based on the story of William Adams. The English later opted to close their factory at Hirado, seemingly because they had not managed to create anywhere near as profitable a trade with Japan as the Dutch.[5]

The Portuguese had been the first Europeans to trade with Japan and had introduced guns and Catholic missionaries. Oda Nobunaga himself had taken advantage of the introduction of firearms to Japan during the Sengoku Jidai. During the Edo period Christians were persecuted and the religion was banned in Japan, and trade with the Portuguese was stopped entirely. Relations with the Spanish seem to have broken down before the ban on trade with the Portuguese.[6] Prior to this breakdown in relations with the Portuguese and Spanish, a Japanese delegation had been sent off to Rome in 1613. They travelled from Japan to the Philippines, Mexico and Spain before finally reaching Rome.[7] Hasekura Tsunenaga, a Christian samurai who served the daimyo Date Masemune, led the delegation. Today statues Haskekura Tsnunenaga can be found in Cuba, Italy, Mexico, and Spain as well as Japan.

A perceived threat from Christianity (particularly in the form of Catholic missionaries), with regard to the Tokugawa and their hold on power, seems to have been a significant factor behind the ban on trade with the Spanish and Portuguese- for whom trade with Japan appeared to be too closely linked with missionaries in the eyes of the bakufu.[8] The idea that their Catholic rivals were rather too enthusiastic, fanatical even, in matters of religion was, according to Laver, happily nurtured by the Dutch and the English.[9] Similar concerns about a threat from certain ideologies seem to have been extended to yōgaku or ‘western learning’ entering Japan via European books.

The idea that some Christians might prove to be a problem for the Tokugawa was not wholly unfounded. A Christian daimyo called Arima Harunobu was caught up in a scandal concerning corruption and was then accused of conspiring to have the bugyō (commissioner) in Nagasaki assassinated.[10] However, it also seems the involvement of Christians in scandals and instances of unrest was sometimes used to justify the stance of the Tokugawa, regardless of whether religion had been the major factor which led to a conflict- so there’s an element of scapegoating there too. The Shimabara Rebellion (1637-38 CE) is now viewed by historians as having been caused by a combination of famine and taxes which didn’t help the situation, but it was nonetheless referred to as though it was a rebellion caused or fuelled by Christians at the time. It had been Japanese Christians who had taken part in the rebellion but the bakufu implied that the Portuguese had smuggled in money and missionaries to deliberately fan the flames of the rebellion, and trade with Portugal was soon brought to an end.[11]

The Dutch, via the VOC or Dutch East India Company, would trade with Japan from their first contact with the nation around 1600 CE, as they began to rival Portuguese trade in the Pacific, and throughout the Edo period. After Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to open to trade with the Americans by threatening them with naval force in 1853, the Americans and the British began to trade with Japan. It was through Dejima that rangaku or ‘Dutch learning’ would enter Japan, with Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751 CE) relaxing the ban on many European books that had been introduced as part of the sakoku. Initially, a lot of the translation work through which these books would potentially make their way into Japan was done by the Chinese, however Tokugawa Yoshimune (who was himself interested in European knowledge) allowed and encouraged the study of the Dutch language so that these books could be translated directly into Japanese.[12] It was through Western books that Japanese artists and artisans would become familiar with Western forms of perspective in art and with still life images, which would later be reflected in ukiyo-e prints.

China still proved to be very influential in Japan in other ways, with the culture of the Ming and Qing dynasties in particular helping to shape Japanese poetry, literature and scholastic thought. Woodblock printing and papermaking had both been introduced to Japan from China long before, during the 8th century.[13] Both processes would allow for the wide dissemination of ukiyo-e prints during the Edo period. Japan also continued trade relations with Korea via the Tsushima Domain.

Edo Period Society

At the top of Edo period society were the emperor and the nobility (who had little actual power), followed by the shōgun (who tried to keep a strong grip on the reins of power), then various daimyo and other feudal lords and their samurai retainers. The shōgun prevented daimyo from making alliances with one another and mustering a military force by having daimyo leave their wives and children in the city of Edo. The practice of keeping hostages wasn’t necessarily new but the fact that it was continued throughout this period may imply it was a suitable enough deterrent for some. Daimyo also had to maintain a suitable residence in Edo according to their rank. The daimyo themselves dwelled in Edo and travelled to their territories in alternate years- with a procession suited to their rank, reminding them and others of their place in the social hierarchy and, it was hoped, preventing them from maintaining a lifestyle above or below their rank.[14] All of this could prove costly.

Although the social hierarchy during the Edo period is often seen as clear cut and rigid, things could be a bit more complex. Samurai might serve as armed retainers to daimyo during this period- but members of this warrior class also took up other jobs we wouldn’t necessarily associate with samurai in popular culture, such as positions as bureaucrats and fire wardens. One of the most well-known ukiyo-e artists (Utagawa Hiroshige) originated from a low-ranking samurai family, who served as fire wardens. Lower down in the social hierarchy were peasants, artisans, craftsmen and merchants. Merchants have often been presented as the lowest in terms of social status, but they were not all necessarily the lowest in terms of wealth and influence.

According to Confucian beliefs, which had made their way into Japan through China, a merchant’s livelihood was not an honourable one. Under this belief system, they were regarded as people who were concerned with profit but did not produce anything themselves. They also did not have the expense of having to keep up appearances in the same way daimyo had and some merchant trade associations were allowed monopolies on certain businesses and allowed to set the price of some goods in exchange for a licensing fee and annual taxes from these organisations- but these organisations did have to submit reports to the bakufu.[15] [16] As samurai did not trade as merchants did at this point (and their income was supposed to come in the form of a fixed stipend from those they served), merchants could end up becoming richer than some samurai, who might struggle to keep up with the cost of living in Edo.[17] Daimyo and samurai might also end up depending on some merchants because they were allowed to act as moneylenders, which could create resentment and unease.

The rights enjoyed by merchants could vary from city to city and from urban areas to more rural areas and, although some merchants accumulated vast wealth, others were not nearly as well-off as those who rose to prominence.[18] Peasant farmers, poorer artisans and the less well off merchants may have sometimes resented the wealth of better off merchants, particularly in times of economic hardship and famine. It wasn’t all smooth sailing for the wealthy merchants either. The bakufu could (and did) order some wealthy merchants to buy leftover grain during the Kyōhō Reforms of the early eighteenth century, which were intended to counteract the falling price of rice at this time.[19] The bakufu could be a bit preoccupied with the price of rice because taxes on rice were a major income stream for the Tokugawa and various daimyo during the Edo period. [20] Of all the Tokugawa to rule over Japan, perhaps none is more associated with rice than Tokugawa Yoshimune- who is even referred to as the ‘rice shōgun’ because of his Kyōhō Reforms.

Merchants, along with artisans and craftsmen, made up the majority of those we call ‘the townsmen’; educated city dwellers who had a bit of money to spare. Numerous sumptuary laws existed to try to restrict who could own and use of certain goods. Some of these laws were specifically aimed at what townspeople or chōnin were allowed to wear. [21] In reality, though, these laws were not always easy to enforce and the existence of such rules indicates that people may have been trying to rise above their perceived social station by donning clothes which were deemed to luxurious for them.

The townspeople developed various interests, which artists and artisans catered to in the cheap prints they produced in the thousands.[22] These images and the interests reflected within them would be shaped by a multitude of factors, such as the growing wealth of some merchants and the interests they could engage in because of their wealth. The lifting of restrictions on some Western books during the eighteenth century would introduce new artistic traditions to Japan, a change reflected in some ukiyo-e prints. What the bakufu thought was permissible in ukiyo-e prints, an art form you might say they ultimately did not really regard as art (or at least not a ‘high’ form of art), would also influence the appearance of and the kinds of prints being produced.

The Origins of Ukiyo-e

Many scholars point to the machi-eshi, urban painters who started to emerge around the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as one of the origins of ukiyo-e. Such painters were anonymous and produced work which was affordable to those who had a bit of extra income to spend on luxuries, and although they were painters they were regarded more as artisans than artists by the elite. At some point these painters went from producing paintings on a certain subject matter, when asked to do so by a customer, to creating objects which could just be sold right away to a wider audience.[23] These crafts could be sold either by the painters themselves touting their wares or be purchased from shops.[24] Melinda Takeuchi gives the example of painted screens from the early seventeenth century, which depict shops selling blank and decorated fans, to illustrate the growing industry in arts and crafts as an increasing appetite for art and decorative pieces emerged among the expanding middle classes of Edo Japan. [25]

Artists and artisans also started to produce woodblock prints to better meet this growing demand for images- giving us the iconic prints we imagine whenever we think of ukiyo-e. There were numerous people involved in the production of such prints, from the publishers (who usually co-ordinated the process) to the artist who painted the original designs on paper, to those who carved the wooden blocks for printing and then the printers. The carvers and the printers had to be just as skilled as the artist who produced the original design. Ukiyo-e prints were printed by hand, with the paper placed on top of the printing blocks and pressure applied by hand with the use of a tool called a baren. Many types of ukiyo-e prints emerged, from prints of famous kabuki actors to landscapes such as Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa (also known as The Great Wave), which was part of his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei) series.

I hope you have enjoyed this exploration of the history of Edo period Japan and the emergence of the ukiyo-e genre. In part two, we will look at the transition from monochrome to colour in ukiyo-e prints.

References

[1] Stephen Turnbull, War in Japan, 1467-1615 (Oxford, 2022), pp.7-8.

[2] Memorandum Addressed to the Nagasaki Magistrates (1635) in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.88-89, Source: Hōseishi Gakkai, ed., Tokugawa kinreikō, vol. 2 (Sōbunsha, 1959), 231.

[3] Exclusion of the Portuguese (1639) in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.88-89, Source: Hōseishi Gakkai, ed., Tokugawa kinreikō, vol. 2 (Sōbunsha, 1959), 232.

[4] Margaret Makepeace (British Library, Lead Curator. East India Company Records), ‘William Adams in Japan- a new digital resource’, 17 November 2020 [https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2020/11/william-adams-in-japan-a-new-digital-resource.html#:~:text=Adams%20joined%20a%20Dutch%20merchant,in%201609%20and%201613%20respectively.]

[5] Rogério Miguel Puga, The British Presence in Macau, 1635-1793 (Hong Kong University Press, 2013), pp.17-18.

[6] M. Antoni J. Ucerler, S. J., ‘The Christian Missionaries in Japan in the Early Modern Period’, in Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (editor), A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions (Leiden, 2018), pp. 329-330.

[7] Mayu Fujikawa, ‘Papal Ceremonies for the Embassies of Non-Catholic Rulers’, in Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (editor), A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions (Leiden, 2018), pp.14-15.

[8] Michael S. Laver, The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony (New York, 2011), pp.33-34.

[9] Laver, The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony (New York, 2011), p.33.

[10] Laver, The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony (New York, 2011), p.136.

[11] Laver, The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony (New York, 2011), p.137.

[12] Grant K. Goodman, Japan and the Dutch, 1600-1853 (Richmond, 2000), pp.65-66.

[13] Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing (University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), pp. 9-10.

[14] Nishiyama Matsunosuke (author) and Gerald Groemer (editor and translator), Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Japan, 1600-1868 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1997), pp. 29-30.

[15] William E. Deal, Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 123-124

[16] Charles D. Sheldon, ‘Merchants and Society in Tokugawa Japan’, Modern Asian Studies 17: 3 (1983), pp. 478-479.

[17] Stephen Turnbull, The Samurai: A Military History (London, 2005), pp.252-253

[18] Sheldon, ‘Merchants and Society in Tokugawa Japan’, Modern Asian Studies 17: 3 (1983), p. 47

[19] Uchida Kusuo, ‘Protest and the Tactics of Direct Remonstration: Osaka’s Merchants Make Their Voices Heard’, in James L. McClain and Wakita Osamu (editors), Osaka: The Merchant’s Capital of Early Modern Japan (Cornell University Press, 1999), pp. 83-84.

[20] Akira Hayami, ‘Population Changes’ in Michael Smitka (editor) The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868 (London, 2012), pp.104-105.

[21] List of Prohibitions Concerning Clothing for Edo Townsmen (1719), in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.27-28, Source: Donald H. Shivley, “Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 25 (1964-65): 129.

[22] Adele Schlombs, Hiroshige, 1797-1858: Master of Japanese Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2022), pp. 28-29.

[23] Melinda Takeuchi, Taiga’s True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan (Stanford University Press, 1992), pp.130-131.

[24] Takeuchi, Taiga’s True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan (Stanford University Press, 1992), p.130.

[25] Takeuchi, Taiga’s True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan (Stanford University Press, 1992), p.130.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Memorandum Addressed to the Nagasaki Magistrates (1635) in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.88-89, Source: Hōseishi Gakkai, ed., Tokugawa kinreikō, vol. 2 (Sōbunsha, 1959), 231.

Exclusion of the Portuguese (1639) in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.89-90, Source: Hōseishi Gakkai, ed., Tokugawa kinreikō, vol. 2 (Sōbunsha, 1959), 232.

Excerpts from a Letter from Ebiya Shiroemon to the Governor-General of the VOC (1642), in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.98-99, Source: Translation adapted from C. R. Boxer, A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam by François Caron and Joost Schouten. Reprinted from the English edition of 1663, with Introduction, Notes and Appendices by C. R. Boxer (London: Argonaut Press, 1935), 89-91.

Excerpts from Kanazawa’s “1642 Chōnin Code”, in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.80-81, Source: James L. McClain, Kanazawa: A seventeenth-Century Castle Town (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1982), 159-160.

Public Notice Board of Edo (1711), in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.81-82, Source: John Carey Hall, “Japanese Feudal Laws III: The Tokugawa Legislation”, pt.3, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 1st ser.,38, no.4 (1911): 320-321.

List of Prohibitions Concerning Clothing for Edo Townsmen (1719), in Constantine Nomikos Vaporis (editor/ translator) Voices of Early Modern Japan: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life During the Age of the Shoguns, Second Edition (London, 2021), pp.27-28, Source: Donald H. Shivley, “Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 25 (1964-65): 129.

Further Reading

Amir Lowell Abu-Jaoude, ‘A Pure Invention: Japan, Impressionism and the West, 1853-1906’, The History Teacher 50:1 (2016), pp. 57-82.

Lawrence Bickford, ‘Ukiyo-e Print History’, Impressions 17 (1993).

William E. Deal, Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Sherry Fowler, ‘Views of Japanese Temples and Shrines from Near and Far: Precinct Prints of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, Artibus Asiae 68:2 (2008), pp. 247-285.

Mayu Fujikawa, ‘Papal Ceremonies for the Embassies of Non-Catholic Rulers’, in Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (editor), A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions (Leiden, 2018), pp.13-54.

Grant K. Goodman, Japan and the Dutch, 1600-1853 (Richmond, 2000).

Geoffrey C. Gunn, World Trade Systems of the East and West: Nagasaki and the Asian Bullion Trade Networks (Leiden,)

Akira Hayami, ‘Population Changes’ in Michael Smitka (editor) The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868 (London, 2012), pp. 74-113.

Ichiro Horide (author) and Edward Yagi (translator), The Mercantile Ethical Tradition in Edo Period Japan: A Comparative Analysis with Bushido (Reitaku University Press, 2019).

Sebastian Izzard, ‘The Bijin-Ga of Utagawa Kunisada’, Impressions 3 (1979), pp. 1-5.

Uchida Kusuo, ‘Protest and the Tactics of Direct Remonstration: Osaka’s Merchants Make Their Voices Heard’, in James L. McClain and Wakita Osamu (editors), Osaka: The Merchant’s Capital of Early Modern Japan (Cornell University Press, 1999), pp. 80-103.

Michael S. Laver, The Sakoku Edicts and the Politics of Tokugawa Hegemony (New York, 2011).

Michael Laver, The Dutch East India Company in Early Modern Japan: Gift Giving and Diplomacy (London, 2020).

David J. Lu, Japan: A Documentary History (New York, 2016).

Mary Davis MacNaughton, ‘Genji’s World: The Shining Prince in Prints’, Art in Print 3:1 (2013), pp. 8-13.

Margaret Makepeace (British Library, Lead Curator. East India Company Records), ‘William Adams in Japan- a new digital resource’, 17 November 2020 [https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2020/11/william-adams-in-japan-a-new-digital-resource.html#:~:text=Adams%20joined%20a%20Dutch%20merchant,in%201609%20and%201613%20respectively.]

Nishiyama Matsunosuke (author) and Gerald Groemer (editor and translator), Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Japan, 1600-1868 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1997).

Andreas Marks, ‘A Country Genji: Kunisada’s Single-Sheet Genji Series’, Impressions 27 (2005-2006), pp.58-79.

Sean P. McManamon, ‘Japanese Woodblock Prints as a Lens and a Mirror for Modernity’, The History Teacher 49:3 (2016), pp. 443-164.

Nobuhiko Nakai and James L. McClain, ‘Commercial Change and Urban Growth in Early Modern Japan’, in Michael Smitka (editor) The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868 (London, 2012), pp. 131-208.

Takehiko Ohkura and Hiroshi Shimbo, ‘The Tokugawa Monetary Policy in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, in Michael Smitka (editor) The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868 (London, 2012), pp. 241-265.

Rogério Miguel Puga, The British Presence in Macau, 1635-1793 (Hong Kong University Press, 2013).

Tom Rassieur, ‘Degas and Hiroshige’, Print Quarterly 28:4 (2011), pp. 429-431.

Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing (University of Hawai’i Press, 2001).

Adele Schlombs, Hiroshige, 1797-1858: Master of Japanese Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2022).

Cecilia Segawa Seigle, Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan (University of Hawai’i Press, 1993).

Charles D. Sheldon, ‘Merchants and Society in Tokugawa Japan’, Modern Asian Studies 17:3 (1983), pp.477-488.

Satoko Shimazaki, ‘The Ghost of Oiwa in Actor Prints: Confronting Disfigurement’, Impressions 29 (2008-2009), pp.76-97.

Matthew Shores, ‘Travel and “Tabibanashi” in the Early Modern Period: Forming Japanese Geographic Identity’, Asian Theatre Journal 25:1 (2008), pp. 101-121.

Melinda Takeuchi, ‘Kuniyoshi’s “Minamoto Raikō” and “the Earth Spider”: Demons and Protest in Late Tokugawa Japan’, Ars Orientalis 17 (1987), pp. 5-38.

Melinda Takeuchi, Taiga’s True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan (Stanford University Press, 1992)

Melinda Takeuchi, ‘Making Mountains: Mini Fujis, Edo Popular Religion and Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”‘, Impressions 24 (2002), pp. 24-47.

Stephen Turnbull, The Samurai: A Military History (London, 2005).

Stephen Turnbull, War in Japan, 1467-1615 (Oxford, 2022).

M. Antoni J. Ucerler, S. J., ‘The Christian Missionaries in Japan in the Early Modern Period’, in Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (editor), A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions (Leiden, 2018), pp. 303-343.