Ivy often goes hand-in-hand with holly whenever we think of Christmas, but how many of us really make use of it in our festive décor these days? Find out all about the history of ivy, from decorations to its use in medicine, in this post by Steph.

For more information on the Art, Health and History project, click here.

Today much of our focus on evergreen festive foliage is fixed on the Christmas tree, a relatively recent and once foreign tradition to these shores but now the star of the show. Sprigs of mistletoe and holly also decorate our houses but how many of us incorporate ivy into our Christmas decorations now? The holly, with its bright red berries (which are toxic to humans, cats, dogs and livestock, by the way), may wear ‘the crown’ as the carol The Holly and The Ivy goes- but ivy once played a pretty important role as a festive decoration. We found other uses for it too.

Many visitors to the University of Manchester’s campus love to visit the Old Quadrangle, which has recently been remodelled as part of the University’s bicentenary celebrations, to admire the architecture. The ivy which has climbed across an exterior wall of the Beyer Building, and has become a well-loved feature of the Old Quadrangle, is not true ivy at all. It’s Boston ivy. Boston ivy is not related to ivy, but is actually a member of the grape family. Venture into Whitworth Park, however, and you’ll find plenty of ivy.

There are a number of different ivy species but the two species native to Britain are Hedera helix, known as ‘common ivy’ or ‘English ivy’, and Hedera hibernica– which is known as ‘Atlantic ivy’ and ‘Irish ivy’. Hedera hibernica is normally found in, you guessed it, Ireland. It can also be found in the west of Britain. Both of our native species of ivy can climb up surfaces. The lobed shape we often associate with ivy is actually that of the young ivy leaf, whereas mature leaves tend to be more heart-shaped. Ivy provides both food and shelter for insects and birds and also helps to provide cover for bats roosting in trees. The flowers normally make their appearance in autumn and the berries ripen between November and January. When ripe, the berries of Hedera helix and Hedera hibernica are black in colour.

Ivy and other evergreens, which do not die back as other plants stand bare and dormant, were natural choices for winter decorations and became associated with eternal life. Ivy also has a somewhat sinister reputation, with many believing that it strangles trees. This idea has been around for some time. Pliny the Elder (23 CE – 79 CE), in his Natural History, described multiple species of ‘ivy’ thus; ‘two principal kinds in the ivy, as in other plants, are the male tree and the female...Each of these kinds of ivy is divided into three other varieties: the white ivy, the black, and a third known as the helix.'[1] Ivy is actually a hermaphrodite, unlike holly. Pliny described a species which bears a flower similar to a rose but is odourless, which implies that perhaps not all of the species he was describing here were, in fact, ivy.

He claimed that ‘Ivy, by clinging to a tree, will strangle it‘.[2] The species he referred to as the ‘white helix’ seems to have been the one which bore the blame here and his description of it certainly sounds more like a slightly vampiric version of the ivy we are used to:

‘The white helix is in the habit of killing trees by depriving them of their juices, and increases to such a degree of density as to be quite a tree itself. Its characteristics are, a very large, broad, leaf, and projecting buds, which in all the other kinds are bent inwards; its clusters, too, stand out erect.‘[3] The description of the leaves and flowers in particular sounds more like a mature, true ivy. Ivy, however, is not a parasite and does not really strangle trees.

As a Symbol of the Season

Ivy, holly and mistletoe were the chief Christmas decorations of choice in Tudor England. They were also joined by bay and rosemary. If you were transported back in time to the sixteenth century, you’d notice a lack of Christmas trees in December and the decorations would be going up later than you might expect. Advent wasn’t for gorging on mince pies and other sugary Christmas treats, which now find their way into shops as early as October, it was a time for religious observance and fasting. The decorations were supposed to go up on Christmas Eve, with mistletoe fulfilling much the same role as it does today.[4] According to Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke, there seems to have been a preference for using ivy ‘mainly to adorn churches, porches and the outsides of houses’.[5] They state that this was perhaps because it was a plant commonly found in graveyards but ‘more likely because it was thought to protect against evil spirits and disaster’.[6]

A Pleasant Countrey New Ditty: Merrily Shewing how to Driue the Cold Winter Away to the Tune of, when Phœbus did Rest, &c., printed in 1625 shows that using ivy as a Christmas decoration continued under the Stuart dynasty.

When Christmas tide,

Comes in like a Bride,

with Holly and Iuy clad:

Twelue dayes in the yeare,

Much mirth and good cheare,

in euery houshold is had [7]

Ivy and other Christmas decorations became a source for the occasional uproar during 1640s and 1650s in England. Pamphlets and other sources detailing instances in which people tried to continue observing Christmas after what is often referred to as the ‘ban on Christmas’ provide us with evidence that ivy and other Christmas paraphernalia didn’t totally disappear during the English Civil Wars (fought between 1642 and 1651) and the Interregnum (1649 – 1660).

In 1647 John Warner, the then Lord Mayor of London, had festive greenery taken down following An Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals– which had been passed by Parliament in June that year. According to a pamphlet written in defence of John Warner, a complaint had been brought before the Lord Mayor that ‘a tumult was gathered together in Cornhil, near Leadenhal, where in despite of Authority they had set up Holly and Ivy on the top of a Pinacle, a high work or building in the middle of the street, which they with these green things had adorned; and made some glory in it.‘[8] G.S. Gent, the author of the pamphlet, stated that when the Lord Mayor, accompanied by the Marshal of the City and others attempted ‘to pul down these gawds‘, they were ‘not suffered to do it, were by the multitude abused‘ and ‘One was in danger to be killed…‘[9]

This aggressive response from the would-be revellers apparently resulted in one Price ap Williams being struck on the head by an officer and, according to G.S Gent, wearing ‘a plaister to his broken pate‘ following his release.[10] Gent’s claim that ‘Envy have spread another Report‘ implies that other sources were saying Williams or others involved in the incident did not simply walk away after being questioned.[11]

This was not the only instance of defiance centred around Christmas festivities during the late 1640s and throughout the 1650s, when celebrations around Christmas and other important festivals (such as Easter) were banned. Solemn reflection during Christmas, rather than making merry, was supposed to be the new order of things. In addition to people making their displeasure known on occasions when they had put up Christmas decorations which were then taken down, people also tried to quietly observe Christmas at church. Rosalind Johnson has examined ‘the evidence for loyalist religion at a parish level’ during these decades.[12] Johnson has found evidence of the observance of Easter, Christmas and other festivals in parish records, including ‘explicit reference on seven occasions in the 1650s’ by churchwardens in Chawton ‘to bread and wine purchased at Christmas’.[13]

A tablecloth in the Whitworth’s collections is decorated with motifs ivy leaves and berries as well as hellebore flowers in the centre of the design, with fleur de lys decorating the borders. It dates back to around 1845 and is made from white linen damask. Both hellebore and ivy have a strong association with winter and Christmas but that doesn’t necessarily indicate that the tablecloth was intended just for winter use. We can see from objects such as this, however, that ivy was at least occasionally being incorporated into decorative motifs at the time within the home, in addition to what we know of the plant itself still being used for decoration.

Across the pond during the late nineteenth century, ivy was among the evergreens recommended for a centrepiece in an article entitled ‘The Christmas Dinner Table’ in the Milwaukee Journal in 1892, which described the pairing of ivy and holly in a centrepiece as being ‘far prettier than you can imagine‘. This centrepiece had been used at a Christmas dinner served in 1891, where it sat atop a damask table cloth with a long mirror in the middle.[14] The centrepiece included some quite novel decorations too, such as ‘tiny gondolas made of celluloid, gilded and tied with gay ribbons‘.[15] It seems the greenery was appreciated just as much as the tiny gondolas, however, and there was no shortage of it. The description of such an elaborate centrepiece sitting upon a damask tablecloth makes me wonder how if tablecloth in the Whitworth’s collections was utilised for such an elaborate decorative purpose.

The custom for using ivy as a Christmas decoration seems to have still been going strong in Britain in the early twentieth century, including with the Suffragettes. In issue 11 of The Suffragette, the weekly newspaper for the Women’s Social and Political Union edited by none other than Christabel Pankhurst, there was article which briefly discussed the closing days of a Christmas sale and the decorations present at the event:

‘The provision stall did an excellent trade, and was bright with holly, mistletoe and ivy for Christmas decorations, and with pot plants suitable for presents- the latter given by Mr. Alexander, the well-known florist in Brook Street, who also kindly lent the palms that adorned the hall.‘- ‘The Christmas Sale’, Friday 27th December, 1912, The Suffragette Vol.1, Issue 11 (London, England).[16]

Ivy continued to be used as a Christmas decoration during the First World War, even ‘in the midst of war’.[17] An article entitled ‘How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont’ in Women’s Leader and the Common Cause in January 1916 detailed how ‘the French soldiers did their part‘ to decorate the Scottish Women’s Hospital at Royaumont, born from a gathering of Scottish Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies, where soldiers from the Western Front were treated.[18] According to the author, the soldiers were tasked with decorating the hospital with ‘greenery and huge branches of mistletoe‘ and apparently they did a very good job of it too; the article describes pillars ‘softened with festoons of ivy‘ to disguise the area where ‘the oak wainscot was torn away‘.[19] It seems the hospital staff threw a rather splendid Christmas party for the soldiers, complete with a Christmas tree, a visit from Father Christmas, presents and an ‘English Christmas dinner‘.[20] On Boxing Day, as a token of their appreciation, they presented Dr Ivens with a bouquet ‘as a representative of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals as a whole, and as a personal tribute to her unfailing sympathy and care.'[21]

Medicinal Uses

Let’s return to early modern England, to have a look at what good old Nicholas Culpeper (1616 – 1654 CE) had to say about ivy. Set all thoughts of ‘poison ivy’ aside; the species referred to under this name are not native to the British Isles, nor are they actually ivy species. Culpeper was a physician, among other things, and so he was interested in how it was thought ivy could be used as a medicinal remedy. Culpeper often placed an emphasis on native plants, which he believed were just as, if not more, effective in medicine and with the added benefit of being easier for people who were not wealthy to acquire.

According to Culpeper, the flowers could be useful for gastrointestinal issues, such as ‘the lask and the bloody flux‘ when combined with red wine.[22] It could, he cautioned, be dangerous in some situations:

‘It is an enemy to the nerves and sinews, being much taken inwardly, but very helpful to them, being outwardly applied.'[23]

Culpeper also described it as having preventative as well as curative properties with regard to the plague:

‘The berries are a singular remedy to prevent the plague, as also to free them from it that have got it, by drinking the berries thereof made into a powder, for two or three days together.‘ [24]

If you guessed that this probably wouldn’t be very effective, if it all effective, then you guessed right. Bubonic plague still has a high fatality rate if not treated quickly with antibiotics, pneumonic plague even more so.

Culpeper cited, among his sources, Pliny the Elder, Aulus Cornealius Celsus (who lived during the first century CE) and Cato the Elder (234 BCE – 149 BCE). You could say that for Culpeper and the sources he drew upon, ivy seems to have been seen as a bit of a cure-all. In his The Complete Herbal, first published as The English Physician in 1652, Culpeper listed the supposed uses of ivy, which were; preventing drunkenness, helping ‘those who spit blood‘, preventing and curing plague, helping to ‘break the stone, provoke urine, and women’s courses‘, easing headaches, cleaning and curing ulcers and wounds and helping those ‘troubled with the spleen‘.[25] He listed his sources as he went along. The sources utilised by Culpeper would have been familiar to his contemporaries and had been utilised by other men of medicine previously.

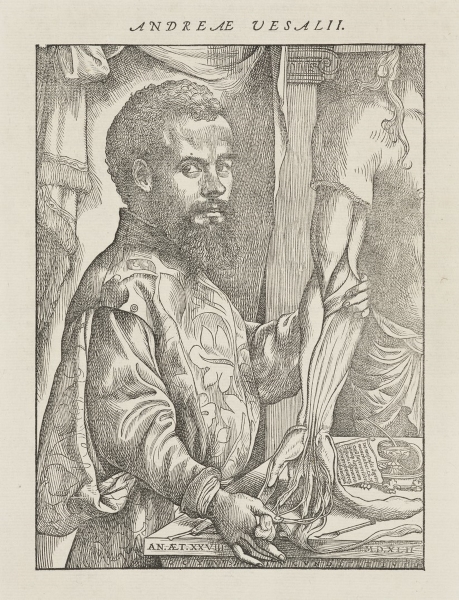

In fact, as an interesting aside and a heads up about your ‘last chance to see’ for those of you interested in the history of medicine, should you pop by to the Whitworth before the 12th January 2025 you’ll be able to feast your eyes on a frontispiece featuring Andreas Vesalius (1514 CE – 1564 CE) in our The ‘Death’ of the Life Room exhibition. Vesalius is known as the ‘father of anatomy’ and is perhaps best remembered for his De humani corporis fabrica libri septem or On the fabric of the human body in seven books, first published in 1543.

Now back to ivy and Culpeper. We can see many of the ideas about the supposed curative properties of ivy repeated in the 1653 edition of Culpeper’s English translation of the Pharmacopœia Londinensis. This edition lists a Hedera Arborea or ‘tree ivy’, under ‘Herbs and Leaves’ in the ‘Catalogue of the Simples Conducing to the Dispensary’ section and states the plant:

‘helps Ulcers, Burnings, Scaldings, the bad effects of the Spleen; the Juyce snuffed up in the nose, purgeth the head, it is admirable for surfets or headach, or any other ill effects coming of drunkenness, and therefore the Poets feigned Bacchus to have his head bound round with them. Your best way is to boyl them in the same liquor you got your surfet by drinking.‘ [26]

The above remedy against drunkenness has a certain ‘hair of the dog’ element to it and is not recommended.

Pliny the Elder had described a species of ivy with ‘a seed of a saffron colour‘, which ‘poets use for their chaplets…the leaves of it are not so black as in the other kinds: by some it is known as the ivy of Nysa, by others as that of Bacchus‘.[27] This description of a plant with seeds of a ‘saffron’ colour is consistent with the colour of the flowers of Hedera helix, also sometimes referred to as ‘tree ivy’, which has a wider geographical distribution than Hedera hibernica. It’s possible that in this case Pliny was actually describing a subspecies of Hedera helix. One subspecies of Hedera helix is known as Hedera helix poetarum or ‘poet’s ivy’. The berries of this subspecies are apparently more yellow or orange in colour when ripe, instead of the black berries of our native species. Hedera helix poetarum is not native to the British isles but the differences between different subspecies of ivy can be quite difficult to spot. So the plant Culpeper described as ‘so well-known to every child almost‘ was likely one of our native ivy species, probably Hedera helix given its wider distribution.[28]

The differences between our native Hedera helix and Hedera helix poetarum don’t seem to have mattered much. This is not surprising for Culpeper in particular, if he was aware that some of his sources may have been describing a certain subspecies of ivy, given his habit of recommending native plants for medicinal use. The use of the term ‘ivy’ in Culpeper’s publications and in the sources he used is not the first instance in which different plants have been referred to under the same common name throughout history; we can see this happened with both false and true hellebores- although at least in the case of instances in which ivy was recommended for drunkenness, many of the plants in question seem to have been true ivy species.

Native species of ivy were still touted by Culpeper and others in England as a remedy for too much indulgence with wine during the seventeenth century nonetheless. Just don’t try it if you indulge too much throughout the festive season! Our native ivy species may not be ‘poison ivy’ but they are somewhat toxic to cats, dogs, horses and humans if ingested.

I can’t say that I have seen many Christmas tree decorations which incorporate ivy into their designs this year. However, I have spotted the odd wreath and other arrangements of festive foliage which indicate that ivy hasn’t entirely been forgotten in our preparations for the big day. Will you be making use of ivy in your décor this Christmas?

– Steph

If you’re interested in the history of the decorative and medicinal uses of other festive plants, check out Steph’s post on hellebore.

Do you want to see other posts from our Whitworth Advent calendar? Click here.

If you want to find out more about the Art, Health and History project, click here.

References

[1] Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVI, Chapter 62, The Ivy- Twenty varieties of it from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

[2] Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVII, Chapter 37, The Diseases of Trees from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

[3] Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVI, Chapter 62, The Ivy- Twenty varieties of it from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

[4] Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (London, 2018), pp.21-22.

[5] Weir and Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (London, 2018), p.22.

[6] Weir and Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (London, 2018), p.22.

[7] A Pleasant Countrey New Ditty: Merrily Shewing how to Driue the Cold Winter Away to the Tune of, when Phœbus did Rest, &c. , 1625. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/pleasant-countrey-new-ditty-merrily-shewing-how/docview/2240849708/se-2.

[8] G.S. Gent, A Word in Season Or, A Check to Disobedience, and to all Lying Scandalous Tongues, with Manifest Conviction of a General Received Slander; in Vindication of the Right Honorable, John Warner, Lord-Mayor of the Honorable City of London : Concerning the Justness of His Actions upon Christmas-Day, Calumniated by Evil-Affected Men. / by G.S. Gent. Jan. 13. 1647. Imprimatur G. Mabbot. , 1648. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/word-season-check-disobedience-all-lying/docview/2240925907/se-2.

[9] G.S. Gent, A Word in Season Or, A Check to Disobedience, p.6.

[10] G.S. Gent, A Word in Season Or, A Check to Disobedience, p.7.

[11] G.S. Gent, A Word in Season Or, A Check to Disobedience, p.7.

[12] Rosalind Johnson, ‘Malignant parties: loyalist religion in southern England’, in Fiona McCall (editor) Church and People in Interregnum Britain (University of London Press, 2021), pp.195-196.

[13] Johnson, ‘Malignant parties: loyalist religion in southern England’, in Fiona McCall (editor) Church and People in Interregnum Britain (University of London Press, 2021), p.206

[14] “The Christmas Dinner Table.” Milwaukee Journal, 13 Dec. 1892, p. 5. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GT3010280389/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=05dd1bdc. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024

[15] “The Christmas Dinner Table.” Milwaukee Journal, 13 Dec. 1892, p. 5.

[16] “The Christmas Sale.” The Suffragette, vol. I, no. 11, 27 Dec. 1912, p. 166. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/BEOXVQ127766671/NCCO?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=f123838c.

[17] V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GMRLEB308419719/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=33a3292b. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

[18] V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522.

[19] V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522.

[20] V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522.

[21] V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522.

[22] Nicholas Culpeper, Complete Herbal, edited by Steven Foster (2019), Text gathered in this modern reprint from the 1653 edition of Complete Herbal and the 1850 edition published by Thomas Kelly of London, pp. 30-31

[23] Culpeper, Complete Herbal, p. 30.

[24] Culpeper, Complete Herbal, p. 30.

[25] Culpeper, Complete Herbal, p. 30-31.

[26] “Pharmacopœia Londinensis, or, The London dispensatory further adorned by the studies and collections of the Fellows, now living of the said colledg … / by Nich. Culpeper, Gent.” In the digital collection Early English Books Online. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A35381.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, pp.13-14. Accessed November 25, 2024.

[27] Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVI, Chapter 62, The Ivy- Twenty varieties of it from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

[28] Culpeper, Complete Herbal, p. 30.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

June 1647: An Ordinance for the Abolishing of Festivals, British History Online (University of London, 2024), Originally published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1911.

A Pleasant Countrey New Ditty: Merrily Shewing how to Driue the Cold Winter Away to the Tune of, when Phœbus did Rest, &c. , 1625. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/pleasant-countrey-new-ditty-merrily-shewing-how/docview/2240849708/se-2. Accessed 28/10/2024

“The Christmas Sale.” The Suffragette, vol. I, no. 11, 27 Dec. 1912, p. 166. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/BEOXVQ127766671/NCCO?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=f123838c. Accessed 28 Oct. 2024.

“The Christmas Dinner Table.” Milwaukee Journal, 13 Dec. 1892, p. 5. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GT3010280389/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=05dd1bdc. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024

Cato, On Agriculture, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. Accessed online 25/11/2024

Nicholas Culpeper, Complete Herbal, edited by Steven Foster (2019). Text gathered in this modern reprint from the 1653 edition of Complete Herbal and the 1850 edition published by Thomas Kelly of London.

“Pharmacopœia Londinensis, or, The London dispensatory further adorned by the studies and collections of the Fellows, now living of the said colledg … / by Nich. Culpeper, Gent.” In the digital collection Early English Books Online. https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A35381.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 25, 2024.

V. C. C. C. “How We Kept Yuletide at Royaumont.” Woman’s Leader and The Common Cause, vol. VII, no. 352, 7 Jan. 1916, p. 522. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GMRLEB308419719/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=33a3292b. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

G.S. Gent, A Word in Season Or, A Check to Disobedience, and to all Lying Scandalous Tongues, with Manifest Conviction of a General Received Slander; in Vindication of the Right Honorable, John Warner, Lord-Mayor of the Honorable City of London : Concerning the Justness of His Actions upon Christmas-Day, Calumniated by Evil-Affected Men. / by G.S. Gent. Jan. 13. 1647. Imprimatur G. Mabbot. , 1648. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/word-season-check-disobedience-all-lying/docview/2240925907/se-2.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVI, Chapter 62, The Ivy- Twenty varieties of it from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, 28/10/2024.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XVII: The Natural History of the Cultivated Trees, Chapter 37, The Diseases of Trees from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, 28/10/2024.

Further Reading

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, #Womenswork100: The Scottish Women’s Hospital at Royaumont, The Royaumont Newsletter Digitisation, <https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/womenswork100-scottish-womens-hospital-royaumont>

Mark Ahonen, Mental Disorders in Ancient Philosophy (London, 2014).

Gerry Bowler, Christmas in the Crosshairs: Two Thousand Years of Denouncing and Defending the World’s Most Celebrated Holiday (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Patrick Curry, ‘Culpeper, Nicholas (1616–1654), physician and astrologer’ (23 September 2004) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 21 Oct. 2024, from https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-6882

Rosalind Johnson, ‘Christmas Under Cromwell: The Hidden Religious Festivals of Interregnum Britain’, 13 July 2021[https://blog.history.ac.uk/2021/07/christmas-under-cromwell-the-hidden-religious-festivals-of-interregnum-britain/],

Rosalind Johnson, ‘Malignant parties: loyalist religion in southern England’, in Fiona McCall (editor) Church and People in Interregnum Britain (University of London Press, 2021), pp.195-216.

David Langslow, ‘The Development of Latin Medical Terminology: Some Working Hypotheses’, Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society No.37 (1991), pp. 106-130.

Roberto Lo Presti, ‘Anatomy as Epistemology: The Body of a Man and the Body of Medicine in Vesalius and his Ancient Sources (Celsus, Galen)’, Renaissance and Reformation Vol. 33, No.3 (2010), pp. 27-60.

Betty S. Spivack, ‘A. C. Celsus: Roman Medicus’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 46, No. 2 (1991), pp. 143-157.

Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (London, 2018).