Read all about the evolution of Santa throughout the centuries in this post by Alex, our Events and Operations Coordinator, just before jolly old Saint Nick drops by on his yearly visit to your home.

The white beard, the rosy cheeks, the red robes, and of course the trademark laugh. There are few more recognisable people in Western iconography and art than Santa Claus, and few with so many different names. But how did the guy we might variously call Father Christmas, Sinterklaas, Jolly Saint Nick or a range of other monikers become such a central figure in so many childhoods? And how much would the original man recognise of himself in all the images we see around us every festive season?

Saint

We know very little about the man who would become Santa. We know he was from Patara and rose to become Bishop of Myra. Far from the North Pole or Lapland, both of these are now in Turkey, at that time part of the Roman province of Lycia. The exact dates he lived are posited as AD 280 to 352, but are heavily debated. Nothing of his own words or voice still exist.

We do know that he exemplified serving others, especially the poor. We know, unlike many Christian saints, that he died peacefully after a long life. He was buried in Myra, where his physical remains stayed for at least nine centuries (more on this later).

In non-physical terms though, he flew the nest very quickly. Within 150 years of his death we know that places of worship dedicated to St Nicholas existed elsewhere along what is now the Turkish coast. Why would this be, and how had this happened?

Part of the reason is possibly due to the most famous story from his life. Whereas now he is associated in a figurative sense with a child’s innocence, the original stories of the life of St Nicholas depict him as a protector of a more literal innocence. Nicholas had an inheritance according to some versions of his story, and used the funds for social responsibility and community service. A once-prosperous merchant had lost his fortune, and had three daughters who would have been forced into prostitution. Nicholas dropped three bags of gold through the merchant’s window each night for three nights, providing them instead with dowries enabling them to marry instead. This story takes place at night and the donation is clandestine – so far, so familiar.

Another prominent story about him tells of him resurrecting three murdered children, and this along with the Three Daughters built up his reputation as a protector of children and influenced artistic depictions of him.

The story of the Three Daughters is unlike most in saints’ narrative cycles. Also unlike most, it is applicable to our own lives. Nicholas’ actions are something we can ourselves look up to and emulate. He is a profoundly human saint.

Traveller

The other major reason for Nicholas’ voyaging ability is that he became one of the major seafaring saints, invoked by those at sea for protection. There are conflicting stories surrounding whether he was one of the decision-making bishops who travelled to the Council of Nicaea in AD325, and outside this major journey it’s unknown whether Nicholas of Myra ever went to sea at all. In this key characteristic, he was possibly conflated with a slightly later saint: Nicholas of Sion, also from Lycia.

It is precisely because of his role as a patron saint of sailors that his name and fame – and his image – was able to spread and diversify. From the port near Myra in Turkey, he travelled far and wide around the Mediterranean, and then beyond. His name became used for places along coasts (e.g. Agios Nikolaos, San Nicola). Early Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land would stop off in his domain, so he travelled with them afterwards like an early version of a tourist souvenir. Where he traveled, eventually he settled, and Constantinople is referenced as having a church dedicated to him as early as the sixth century. His seafaring nature is also behind his survival over hundreds of other saints condemned to obscurity – dividing and conquering with smaller coastal churches in many less significant places, rather than dominant roles in large places subsequently invaded and conquered as with Constantinople.

From Constantinople, the cult of St Nicholas travelled along with Byzantine Christianity up to the Black Sea and thence via rivers to Eastern Europe and Russia in the ninth century. There he branched out to become more broadly a patron saint of travellers, with an early church being founded in Kiev in 882. The stories of his acts of kindness and charity proliferated and he developed the epithet Nicholas the Helper (Nikolai Agodnik). In the Eastern Orthodox Church there is an oral tradition of reciting saints’ lives annually on their feast day, and Nicholas’ feast day on 6th December became associated with emulating his selfless acts.

In the twelfth century he was described by Byzantine chronicler Anna Comnena as the “greatest saint in the hierarchy”. This was written just after soldiers from the city of Bari in Italy, itself like England newly conquered by Normans, had journeyed to Myra in 1087 and seized at least part of the hitherto intact body of St Nicholas. It was a daring act of politics rather than religion, bringing more prominence to Bari and legitimacy to the Norman rule of it. Bari only a few years later was a major stopping point for crusading knights, who were able to have a seafaring saint right on hand to pray to – himself as they saw it someone who had recently fled from invading Turks – before setting sail for the Holy Land, and then taking St Nicholas with them to still further flung areas of Christendom.

However, crusading and acquisitive knights came from various places. Venice, a city which depends on water, was also a base from which Crusade fleets departed. Having stopped off in Myra on the way to the Holy Land in 1100, they ‘acquired’ whatever remained of St Nicholas’ body. Whatever the truth of where exactly the saint’s physical remains are, both Bari and Venice have further added to the ability for his story to travel and evolve, along with his appearance.

From these Adriatic stepping-stones came western Europe, with Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk being dedicated to St Nicholas around 1300. It is here that he takes on other names such as Sinterklaas.

Legend

His survival and continuation in Protestant Netherlands owed much to the humanity of his story, the relatability of his narrative and especially the Three Daughters. By the 16th century, households across northern Europe were beginning to incorporate gift-giving to children on St Nicholas’s feast day in his name, in a way perpetuating the idea of saintly miracles even at the height of the dissolution. St Nicholas, unlike many saints, could be transposed into secular settings, and then take on regional variations with the added freedom that brought.

The real turning point in our guy’s history is going along for the ride with Dutch people colonising what is now New York: they took stories of Sinterklaas with them. This transfer across the Atlantic can be traced to his longstanding association with safe travel at sea. It would be natural that people embarking on a scary journey to the unknown might find security in familiar and comforting talismans relied upon by generations of their ancestors, despite themselves adhering to their new Protestant faith.

Gradually, after clinging on in folk customs for a century or so, St Nicholas shifted from his traditional feast day earlier in December, and more symbolic gifts of cookies and oranges, to the end of the month. This was influenced by the richest families in Manhattan, many of whom had Dutch ancestry, adopting the English custom of giving gifts at New Year. The support from and embedding in routine of elite and influential people in New York gave the real impetus needed to propel the Eastern Mediterranean 4th century bishop to stardom.

Several popular literary works from the first half of the 19th century served to further cement his central place in the festive period; one 1822 work by Clement Clarke Moore that we now know more by its first line, Twas the night before Christmas, uprooted him again and gave him a Christmas Eve role. Their descriptions of him were also very formative for the images of him we see today.

A different kind of icon

A major factor in Nicholas’ success and his current status is the adaptability of his image. The tradition says that even though he may have been imprisoned under Emperor Diocletian, he died peacefully in old age. This contrasts with many saints of this period who were martyred and who are depicted with items related to their suffering or their gruesome and agonising deaths (St Sebastian with arrows, St Catherine with a broken wheel). Scenes from saints’ lives adorned the walls of churches across Europe and beyond, including in England prior to the dissolution. Christian medieval minds – for whom seeing imagery at all was mostly confined to within the walls of churches – would have been able to “read” these scenes and identify these recognisable individuals much as we might interpret the images in a comic strip today and recognise certain characters by their outfits and accessories.

The imagery of St Nicholas in the orthodox Christian Church is much more consistent. Once his stories reached Roman Catholic western Europe the iconography diversified. Even prior to a world where we can instantly share imagery both real and fake, images of St Nicholas were created using different techniques, different styles, different mediums, on different materials. It was likely to have been one of the saints’ stories depicted by early groups of players, or mummers.

He is shown with and without his Bishop’s accoutrements in western iconography. As fashions changed for both clothes and religion, so too did he, adapting to more secular imagery to almost disavow him and his cult from the Church itself. By the 16th century in the Netherlands he was well and truly wearing the fashion of the times – even depicted sometimes with a tobacco pipe.

As the imagery of St Nicholas himself changed, so too did other things about his story. Gradually the window that Nicholas delivered gold through morphed into a chimney (something which did not exist in 4th century Turkey), an early example being a 14th century fresco near Belgrade in Serbia. The story of three bags of gold in the Three Daughters story became three globes in Roman Catholic iconography of St Nicholas, a symbol later to be co-opted by pawnbrokers.

The 19th century and the Victorians are responsible for a great deal of how we live today – from how we sleep to how we eat – but they also founded many traditions about Christmas, even small details. Santa having reindeer, travelling by sleigh, living at the North Pole: these can all be traced back to 19th century New York (the Dutch had had him originating in Spain).

The aforementioned stories about him in early 19th century New York adapted not just his name – having been over the centuries since the Dutch colonised variously Santiclaus, Sinti Klass, St Claas, Santaclaw and so on – to an agreed spelling of Santa Claus, but also his accessories. New York in December demands appropriate layers, which led to Santa wearing warm clothes and furs. He put on weight and his beard grew larger.

The second half of the 19th century embedded him as a central figure in Christmas itself. He migrated back across the Atlantic to England where he became merged with the folk figure Father Christmas – a merry personification of the festive period. In the USA he expanded still further and was popularised in Thomas Nast’s illustrations for Harper’s Weekly.

Many of these early illustrations were open to interpretation for the reader because they were in black and white. Although it is fair to say that Coca-Cola helped to popularise Santa wearing red rather than green robes, there are depictions of him wearing red – and descriptions – that far predate his first appearance in their advertisements in 1931.

Santa at the Whitworth

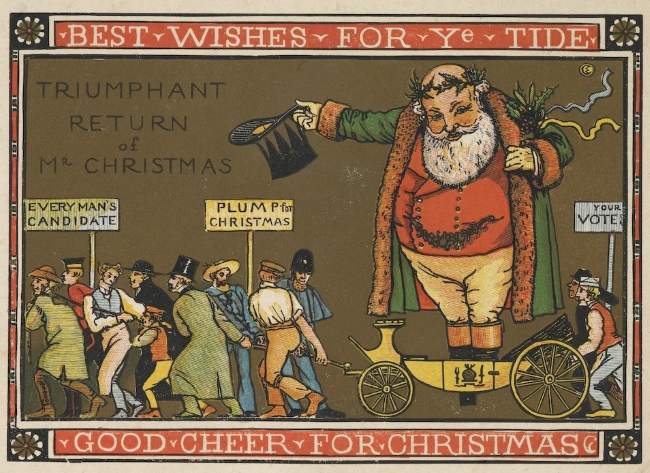

Let’s now take a look at some images from the Whitworth collections. They are by the artist Walter Crane, and are very characteristic of the Arts and Crafts movement. In these three images you can see different incarnations: St Nicholas the saint and protector of children, a personification of December clutching a Christmas tree and wearing more luxurious furs and a classic Dutch pilgrims’ hat, and jolly man-of-the-people Mr Christmas with his crown of holly leaves. Folk figures and traditions like Father Christmas were beloved by Crane and his ilk, and comparing Crane’s images side by side you can really see how the English in the late 19th century took the New Yorkers’ Santa Claus and saw so many similarities in their own personification of Christmas.

The real Nicholas lived in a land that has been part of various empires – Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman – but his legend has forged his own empire in a way, more figuratively.

The story of the Three Daughters – illustrating a relatable and tangible way to Do Good – evoked and still evokes a charitable ideal that has appealed to generations of people throughout numerous societies, and may be a key reason for the story of St Nicholas surviving and being so transferable. His role as a protector of sailors is crucial to his proliferation and expansion.

When thinking about how St Nicholas spread and grew into who we know as Santa, you get a real sense of the organic nature of history: driven by real people taking things that brought them comfort across continents and oceans, developing stories and imagery that can resonate for new generations.

– Alex