Dive into Santiago Yahuarcani’s El mundo del agua, and uncover the history and traditions behind his work in today’s blog post by Sev. Santiago Yahuarcani: The Beginning of Knowledge is on display at the Whitworth from 4th July 2025 – 4th January 2026.

For artist Santiago Yahuarcani, his artistic process is less about creating aesthetically pleasing pieces, and more about telling a story. The piece El mundo del agua, which I will be primarily writing about today, encapsulates an ethos, a cosmology and a connection with nature which has been close to the brink of extinction for more than a century. Born in Pebas, Northern Peru in 1965, Yahuarcani belongs to the Aimeni or White Heron clan of the Uitoto people (also Witoto or Huitoto). The Uitoto rely heavily on the Amazon River for their resources. It provides a unique eco-system which is essential to their way of life. Fish, herbs and medicinal plant species endemic to the banks of the river here have fuelled the lifeforce of the Uitoto people for many centuries.

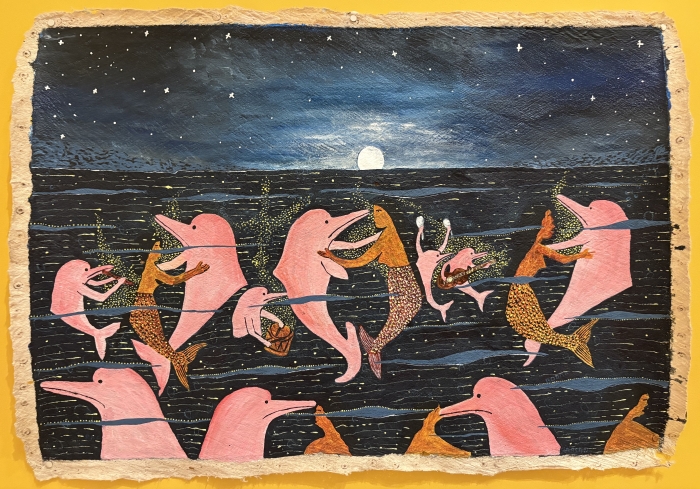

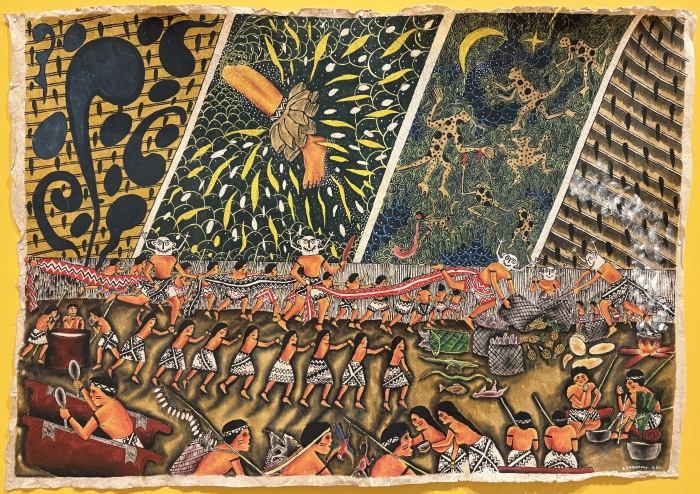

El mundo del agua depicts a scene of the Amazon River which is teeming with life – and not all of it is familiar. In Uitoto cosmology, the human world is balanced with the spirit world. The spirits teach the people of the Amazon rainforest how to fish, hunt and gather without decimating the forest’s resources. In other words, balance is essential. Yahuarcani depicts the spirits as otherworldly, hybrid creatures. Sometimes part human, sometimes part animal, and sometimes indistinguishably neither.

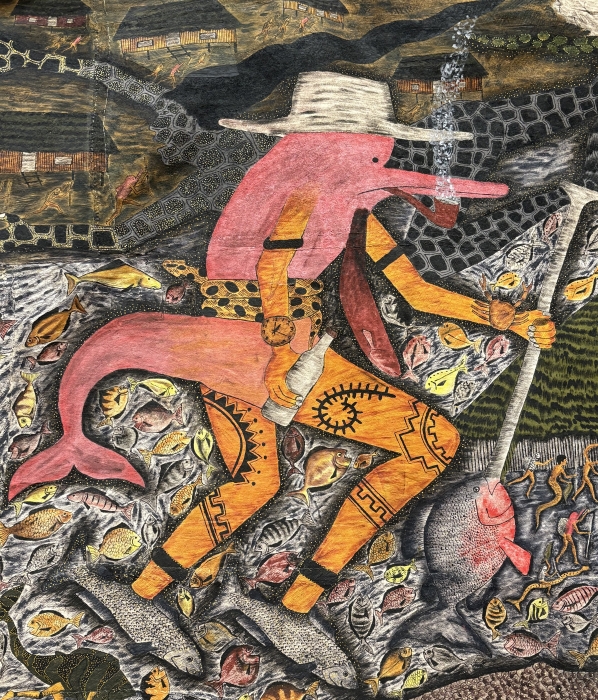

The figure pictured above, who has a fishtail for a foot and a heron’s leg for a staff, appears to be dressed in a traditional Uitoto mask – the likes of which Santiago Yahuarcani’s wife, Nereyda Lopez, still creates today.

If it weren’t for the fishtail foot, this spirit may have easily been mistaken for a human.

The spirit dominating the piece is no different, and she seems to be the defining force behind it all. She is almost mermaid-like, though perhaps more sinister than what we as western audiences might consider when we think of mermaids. Whether that should be attributed to the snake protruding from her belly or the half-fin half-foot at the end of her tail, or the strange, hypnotic patterns on her skin, remains subjective.

It is details like these; the strangeness of the anthropomorphic spirits and the details given to each tiny fish, which I have noticed most visitors picking up on when they first walk into the space and take in this gigantic work. The scale of it, in all its epic proportions, highlights how highly Yahuarcani regards the Amazon River and the spirits which inhabit it.

Like much of Yahuarcani’s works, however, it alludes to a dark history. At first glance, it is a bright, colourful piece teeming with life and mystery. On a second glance, it becomes something more.

From 1879 to 1930, the indigenous peoples of the Amazon Rainforest were subject to a genocide which largely took place in the Putumayo River Basin, Colombia. After the invention of vulcanized rubber, the Amazon Rainforest became the focus of mass industrialisation and huge political change. The genocide was primarily perpetrated by a Peruvian entrepreneur and rubber baron, Julio Cesar Arana, who registered his company, The Peruvian Amazon Company, with the London Stock Exchange during the Amazon Rubber Boom.

He and other rubber barons enslaved thirty-four indigenous communities, the Uitoto being one of them, to collect this rubber at great cost to their culture and lives. The atrocities committed against these communities are too many to mention, but by the end of it, the indigenous population was greatly reduced.

In 2009, efforts were made by the Colombian Constitutional Court to lead Ethnic Safeguarding Plans (ESP’s). These ESP’s were brought in to protect the thirty-four groups affected by genocide and forced displacement after they came close to cultural extinction. A constant dialogue between local communities and governments is essential in these proceedings, lest the communities become subject to globalizing international laws which would, undoubtedly, only serve to further dilute their cultural identity.

Yahuarcani’s work is almost never separate from this dialogue. His body of work depicts a great inherited struggle, the origins of which were orally passed down to him from his grandparents, who were both survivors of the genocide. Their story tells of decades of oppression, indentured slavery, and the decimation of large swathes of the forest. Yahuarcani’s works are a continuing odyssey of constant efforts made by colonialists to rob the Uitoto (and, indeed, the thirty-three other indigenous groups) of their ways of life. They tell us about the genocidal crimes of the past, and the eco-cidal crimes of the present. El mundo del agua is no exception.

Hidden amongst the brimming, eclectic life, are references to the genocide. In the background, the Maloca (a traditional circular, communal building which was taken over and utilized as holding quarters by slave drivers during the Putumayo genocide) looms – stark, heavy and oppressive. Easy to miss at a first glance, but unmistakable once noticed, it sticks out; a solid human structure amidst the chaos and collision of nature and spirits.

Beside it, stands a spirit; a pink river dolphin. In Uitoto mythology, the pink river dolphins (bufeos) are shapeshifters. It is said that at night, male river dolphins would shapeshift into humans, covering the blow-holes on their heads with hats. They would then march out onto land and party with the humans. Much of this ‘partying’ included stealing and drinking alcohol and sleeping with the local women. Many unexplained pregnancies were said to have been blamed on the pink river dolphin.

In El mundo del agua, a river dolphin shapeshifter wears a white hat which, and I don’t think this is a coincidence, resembles the uniforms the slave drivers used to wear. Depicted in many other of Yahuarcani’s paintings, these foremen were always dressed in white, with wide-brimmed hats just like this one. In this piece, the shapeshifting river dolphin is also smoking a pipe and holding a bottle of what could, presumably, only be alcohol. It seems to me that Yahuarcani is referring to the exploitative actions of the slave drivers – i.e the pillaging of local resources, commodities and, indeed, women – via the myth of the shapeshifting dolphin. He wears a clock on his wrist which appears to say to the viewer: time is ticking! A reminder from Yahuarcani, for those who know, that the ever-present threat of persecution from powerful outsiders remains.

At the top right-hand corner of the piece, Yahuarcani has painted a small city-scape. Skyscrapers and tall buildings towering over the land. In the top left, there are buildings which resemble those from Yahuarcani’s own community in Pebas. Wooden structures which meld with the forest. The contrast drawn here conveys an understanding that without the ecological resources of the Amazon Rainforest, neither would exist. The main difference is that one was built on long decades of destruction, whilst the other respects the balance of the forest and does not take more than it needs.

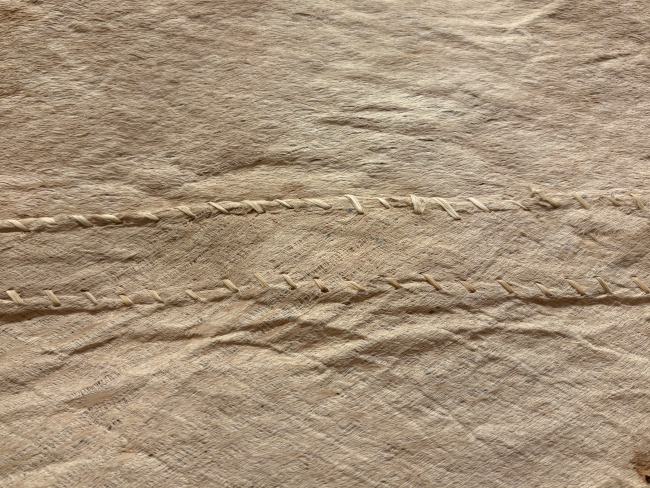

Almost everything, from the natural dyes that Yahuarcani uses to mix his paint, from the material he paints on – a bark called llanchama – is taken from the forest with great care. The art of harvesting llanchama, for example, is an indigenous tradition which dates back centuries, and has traditionally been used to create clothing and baskets.

Llanchama is harvested from a species of fig tree, called the Renaco tree, and it has a natural woven quality which makes it an attractive material for cloth making. Traditionally, to make cloth, the llanchama would be taken off the tree in strips, draped in the water of the Amazon River, and beaten to soften the fibres. This process would take days for many people to do, and up to a week for just one person. As it stands, the llanchama Yahuarcani uses is largely untreated, so the fibres remain stiff and absorbent. Llanchama, too, has a natural balance which indigenous peoples were careful not to disturb.

There are two types: red llanchama and white llanchama. The red was more commonly used, though it isn’t a consistent colour throughout. White llanchama was more desirable, due to its lack of aesthetic imperfections, but it was more difficult to harvest because, most of the time, it contains a sap which is irritating to the skin. Once a month on the full moon, however, this sap loses its potency and can be safely harvested. The people who have used llanchama and continue to use it to this day remain aware of this fact, and respect the cycle of the plant to maintain their balance with the forest and the spirits who inhabit it alongside them.

Yahuarcani often makes large paintings, and to do this he has to stitch together pieces of llanchama until he can achieve the desired size. The stitching and natural features of the tree bark can be seen very clearly in El mundo del agua.

I think it is telling that Yahuarcani makes no aesthetic effort to hide these stitches or imperfections in the llanchama. They are as much a part of the piece as the painting is. They tell the story of the llanchama and where it comes from. He approaches the material with no shame or qualms about where it came from, or what he is using it for. It is as much a statement as it is a practical decision. It shows that the Amazon Rainforest – its multitude of rich resources – and its people, have not been completely decimated yet. It is a protest against the artificiality of today’s world, and the ongoing efforts to extinguish ecological conservation practices. Yahuarcani’s message in this work is clear: The Putumayo genocide may have passed, but its legacy is as alive and as prevalent now as it was since the day it began. – Sev

Resources

Andrea Fanta Castro, Alejandro Herrero-Olaizola and Chloe Rutter-Jensen, Territories of Conflict: Traversing Colombia through Cultural Studies (2017).