Today Steph is back with part 2 of her investigation into the uses of mistletoe throughout the ages.

Read Part One.

Continuing from part one of Mistletoe: ‘Medicine’, Murder and the Festive Season, today we will take a more detailed look at some of the historic medicinal uses of mistletoe and try to track the mistletoe’s journey as festive flora.

Strange Remedies

In The English Physician: Enlarged, Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654 CE) claimed mistletoe was ‘under the Dominion of the Sun’ but mistletoe growing on an oak tree would also have some of the nature of Jupiter, as the oak was associated with Jupiter. [1] Culpeper was writing about European mistletoe, which he noted ‘groweth very rarely on Oakes with us’ and he expressed his confusion as to why mistletoe found on an oak should be considered the best unless it was because this mistletoe would be rare.[2] This idea that mistletoe found on oak might be better and more effective than other mistletoe seems to repeat the claims found in Pliny’s Natural History. Culpeper was familiar with Pliny the Elder’s work, which he wrote in other parts of The English Physician.

The English Physician: Enlarged also referred to the work of French botanist Carolus Clusius (1526-1609 CE), whom Culpeper claimed said that mistletoe ‘being hung about the Neck, it remedies Witchcraft.’ [3]

In addition to acting as a remedy against supernatural threats, Culpeper credited mistletoe with other powers:

‘Both the leaves and berries of Misselto do heat and dry; are of subtil parts, the birdlime doth mollifie hard Knots, Tumors and Imposthumes, ripeth and discusseth them; and draw forth thick as well as thin humors from the remote parts of the body, digesting and separating them. And being mixed with equal parts Rozin and Wax; doth mollify the hardness of the Spleen, and healeth old Ulcers and Sores’. [4]

Culpeper also discussed the supposed usefulness of mistletoe in remedies for ‘foul nails’, as well as for curing ‘the Falling-sickness‘ (epilepsy) and ‘Apoplexie, and Palsie very speedily’. [5] For epilepsy, Culpeper described the cure as involving mistletoe found on an oak tree being ground into a powder and consumed in a drink.

I found that in some publications, it wasn’t just powders made from mistletoe which were recommended as a cure. Some of the sources I encountered, such as Joseph Blagrave’s New Additions to the Art of Husbandry (1675) and Nicholas Cox’sThe Gentleman’s Recreation in Four Parts (1686) discussed the belief that the poor ‘mistle-throstle’ (mistle thrush), when ground into a powder and mixed into a drink made with ‘the distilled Water of Misletoe-Berries, or Black-Cherry Water’, might be an effective treatment against ‘the Falling-sickness and Convulsions’ because the bird eats lots of mistletoe berries [6] [7] Joseph Blagrave did at least state that he ‘never did experiment the truth’ of this belief but he also thought that it made sense and that mistletoe could help with epilepsy in horses. [8] Mistletoe is toxic to horses, so please do not try any of these old remedies horses or other animals. And please don’t kill mistle thrushes.

Looking back to ancient Rome briefly, Aulus Cornelius Celsus (who also lived during the first century CE like Pliny the Elder) may give us a better idea than Pliny about what kind of medicinal uses some Romans thought mistletoe had. Due to the influence of Greek and Roman ideas on medicine in Europe in later centuries, we can see some similarities between what Celsus said about the supposed medicinal uses of mistletoe and what early modern authors like Culpeper said about mistletoe. Culpeper was also familiar with the work of Celsus, which he referred to in The English Physician. De Medicina was lost for some time, but it was rediscovered near the end of the Middle Ages. After the invention of the printing press, De Medicina was published in print in 1478.

For Celsus, mistletoe was best used as an ingredient in treatments used like ointments, some of which were used to try to help with pain:

‘For pains in the sides there is the composition of Apollophanes: turpentine-resin and frankincense root, each 16 grams, bdellium, ammoniacum, iris, calf’s or goat’s kidney-suet, mistletoe juice, each 16 grams. This composition relieves pain of all kinds, softens indurations, and is moderately heating.’ – Aulus Cornelius Celsus, De Medicina, Book V, Chapter 18. [9]

Another recipe which used mistletoe as an ingredient was recommended for pain management as well as many other uses:

‘The emollient of Andreas is for like use; and it also relaxes, draws out humour, matures pus, and when it is matured ruptures the skin, and brings a scar over. It is applied with advantage to abscesses, both small and large, likewise to joints and so both to the hips and feet when painful; further, it repairs any part of the body that is contused; also softens the praecordia when hard and swollen; draws outwards splinters of bone — in short, is of service in all cases which heat can benefit. It is composed of wax 4 grams, mistletoe juice…’ – Aulus Cornelius Celsus, De Medicina, Book V, Chapter 18. [10]

I’m not sure if the juice from the mistletoe berries may have caused skin irritation for some people.

Mistletoe as Festive Flora

How did mistletoe end up being made a part of winter festivities? The inclusion of mistletoe in winter festivities is often credited to the Romans, who celebrated Saturnalia (which honoured Saturn) in December, and to the Druids. Saturn was a god of agriculture and wealth, but he is probably best known for eating his own children so they couldn’t replace him as ruler of the gods. As Saturnalia took place in winter, evergreen plants were used as decorations, so it’s possible that mistletoe was used too.

However, Saturnalia was not Christmas and the tradition of kissing under the mistletoe at Christmas may not be very old at all. One of the earliest mentions of the custom that I could find dates to the year 1800 in a poem called The mistletoe.— A Christmas Tale. [11] The poem was written by Mary Robinson (1757-1800) and may have been published first under the name Laura Maria.

An earlier reference I found dates to 1791 and was printed in an article in the Star and Evening Advertiser, which discussed the supposed customs of the Druids. It said that the custom of kissing under the mistletoe came from the Druids using mistletoe ‘to prevent sterility’. [12] Most of the article seems to have repeated things Roman sources said about the Druids, and it suggests that because the Druids associated mistletoe with fertility, kissing under the mistletoe must be an ancient tradition. I could not find any primary source material which mentioned the tradition of kissing under the mistletoe dating back to before the 1700s.

Now on to the 19th century. This was the period when mistletoe and Christmas became even more intertwined, with Christmas cards emerging as a new Christmas tradition and probably contributing to this. Victorian Christmas cards can range from what many people might think of today as a more traditional Christmas card to cards which look a bit strange and creepy. Christmas cards with jokes on them were also available to buy during the late 19th century.

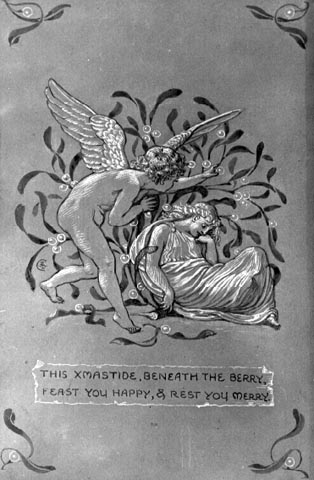

One design for a greetings card in the Whitworth’s collection features two figures surrounded by what I think is European mistletoe. The winged figure bends toward a sleeping woman dressed in a dress which appears to be inspired by clothing worn in ancient Greece or Rome. The scene reminds me of the story of Cupid and Psyche, especially the scene when Cupid wakes Psyche up after she is tricked into opening a box which contains sleep.

Underneath the image of the two figures is the text ‘This Xmastide, Beneath the berry, Feast you happy, & Rest you merry.’ Like many of the greeting card designs in the Whitworth’s collection, this design was created by the artist Walter Crane (1845-1915), an important figure in the Arts and Crafts movement and a friend of William Morris. The design dates to around 1877-1879. By the 1870s, Christmas cards were a new Christmas tradition in Britain, and they were produced in different shapes and sizes and for different budgets.

But if you lived in Britain or America in the late 1800s or early 1900s and wanted to buy some real mistletoe for your Christmas party, where was the mistletoe coming from?

I found one article from 1906 which mentioned mistletoe grown in England being on sale at markets in Manchester, but the article also stated that Manchester was ‘almost the only town’ where people could buy English mistletoe and that large amounts of mistletoe were imported from France. [13] A 1920 article in The Sunday Times stated that the mistletoe on sale in Covent Garden that year had been imported from France. [14] An article published in the Daily Inter Ocean in 1888 claimed that the custom of kisssing under the mistletoe ‘as well as the mistletoe, is imported from England’ but the amount of mistletoe available in New York that year would be ‘scarce’. [15]

If you want to buy some English mistletoe for you own Christmas celebration next year then you could go to Tenbury Wells, in Worcestershire, which is home to old orchards and mistletoe and still hosts mistletoe auctions. [16] It has been called the ‘Mistletoe Capital’ of England because of its history with mistletoe, which has been grown at Tenbury Wells for over a hundred years. [17] The Tenbury English Mistletoe Enterprise group have even created some new mistletoe traditions. [18]

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! – Steph

References

[1] Nicholas Culpeper, (1616-1654). The English Physitian Enlarged with Three Hundred, Sixty, and Nine Medicines made of English Herbs that were Not in any Impression Until this … : Being an Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Vulgar Herbs of this Nation : Containing a Compleat Method of Physick, Whereby a Man may Preserve His Body in Health, Or Cure Himself, being Sick, for Three Pence Charge, with such Things Only as Grow in England, they being most Fit for English Bodies … / by Nich. Culpeper, Gent. .. , 1653. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2., pp.160-161, accessed online 24/11/2025

[2] Culpeper, (1616-1654). The English Physitian Enlarged, ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2., c.1653, p.161, accessed online 24/11/2025

[3] Culpeper, (1616-1654). The English Physitian Enlarged, ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2., c.1653, p.161, accessed online 24/11/2025

[4] Culpeper, (1616-1654). The English Physitian Enlarged, ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2., c.1653 p.161, accessed online 24/11/2025

[5] Culpeper, (1616-1654). The English Physitian Enlarged, ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2., c. 1653, p.161, accessed online 24/11/2025

[6] Joseph Blagrave, (1610-1682). New Additions to the Art of Husbandry Comprizing a New Way of Enriching Meadows, Destroying of Moles, Making Tulips of any Colour : With an Approved Way for Ordering of Fish and Fish-Ponds … with Directions for Breeding and Ordering all Sorts of Singing-Birds : With Remedies for their several Maladies Not before Publickly made Known. , 1675. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/new-additions-art-husbandry-comprizing-way/docview/2240893181/se-2, pp. 88-89, accessed online 24/11/2025.

[7] Nicholas Cox fl.1673-1721. The Gentleman’s Recreation in Four Parts, Viz. Hunting, Hawking, Fowling, Fishing : Wherein these Generous Exercises are Largely Treated of, and the Terms of Art for Hunting and Hawking More Amply Enlarged than Heretofore : Whereto is Prefixt a Large Sculpture, Giving Easie Directions for Blowing the Horn, and Other Sculptures Inserted Proper to each Recreation : With an Abstract at the End of each Subject of such Laws as Relate to the Same. , 1686. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/gentlemans-recreation-four-parts-viz-hunting/docview/2240909545/se-2, pp. 164-165, accessed online 24/11/2025

[8] Blagrave, (1610-1682). New Additions to the Art of Husbandry, ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/new-additions-art-husbandry-comprizing-way/docview/2240893181/se-2, c.1675, p. 88, accessed online 24/11/2025.

[9] Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina. W. G. Spencer. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1971 (Republication of the 1935 edition), Accessed online at Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, on 25/11/25

[10] Celsus. De Medicina. W. G. Spencer. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1971 (Republication of the 1935 edition), Accessed online at Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, on 25/11/25

[11] Mary Robinson. The mistletoe. — A Christmas tale. By Laura Maria. Published 12th Sepr. 1800 by Laurie & Whittle. 53, Fleet Street, London, 1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0110177458/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=9347b877&pg=1. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

[12] “Business.” Star and Evening Advertiser [1788], 27 Dec. 1791. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/Z2001423638/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=3&xid=512e5630. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

[13] “The Neglected Mistletoe.” Grantham Journal, 29 Dec. 1906, p. 3. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/JF3230269777/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=3&xid=96b3c108. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

[14] “First Mistletoe on Sale.” Sunday Times, 5 Dec. 1920, p. 15. The Sunday Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/FP1802469729/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=15&xid=6445aac6. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

[15] “Mistletoe.” Daily Inter Ocean, 23 Dec. 1888, p. 11. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GT3003211964/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=11&xid=c41dc9e8. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

[16] Johnathan Briggs, ‘The Festival Beginnings’, Tenbury English Mistletoe Enterprise, 2025, https://tenburymistletoe.org/teme

[17] Johnathan Briggs, ‘The Festival Beginnings’, Tenbury English Mistletoe Enterprise, 2025, https://tenburymistletoe.org/teme

[18] Johnathan Briggs, ‘The Festival Beginnings’, Tenbury English Mistletoe Enterprise, 2025, https://tenburymistletoe.org/teme

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Joseph Blagrave, (1610-1682). New Additions to the Art of Husbandry Comprizing a New Way of Enriching Meadows, Destroying of Moles, Making Tulips of any Colour : With an Approved Way for Ordering of Fish and Fish-Ponds … with Directions for Breeding and Ordering all Sorts of Singing-Birds : With Remedies for their several Maladies Not before Publickly made Known. , 1675. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/new-additions-art-husbandry-comprizing-way/docview/2240893181/se-2.

Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina. W. G. Spencer. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1971 (Republication of the 1935 edition), Accessed online at Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, on 25/11/25

Nicholas Cox fl.1673-1721. The Gentleman’s Recreation in Four Parts, Viz. Hunting, Hawking, Fowling, Fishing : Wherein these Generous Exercises are Largely Treated of, and the Terms of Art for Hunting and Hawking More Amply Enlarged than Heretofore : Whereto is Prefixt a Large Sculpture, Giving Easie Directions for Blowing the Horn, and Other Sculptures Inserted Proper to each Recreation : With an Abstract at the End of each Subject of such Laws as Relate to the Same. , 1686. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/gentlemans-recreation-four-parts-viz-hunting/docview/2240909545/se-2.

Nicholas Culpeper, 1616-1654. The English Physitian Enlarged with Three Hundred, Sixty, and Nine Medicines made of English Herbs that were Not in any Impression Until this … : Being an Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Vulgar Herbs of this Nation : Containing a Compleat Method of Physick, Whereby a Man may Preserve His Body in Health, Or Cure Himself, being Sick, for Three Pence Charge, with such Things Only as Grow in England, they being most Fit for English Bodies … / by Nich. Culpeper, Gent. .. , 1653. ProQuest, https://manchester.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/english-physitian-enlarged-with-three-hundred/docview/2240956895/se-2.

Andy Orchard (editor and translator), The Elder Edda (London, 2011). Penguin Classics Edition.

Mary Robinson. The mistletoe. — A Christmas tale. By Laura Maria. Published 12th Sepr. 1800 by Laurie & Whittle. 53, Fleet Street, London, 1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0110177458/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=9347b877&pg=1. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder), Natural History, Book XVI, Chapters 93, 94 and 95 from The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Accessed online at Gregory R. Crane, Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, accessed online 24/11/2025.

Snorri Sturluson (author) and Jesse Byock (translator), The Prose Edda, (London, 2005). Penguin Classics Edition.

“Business.” Star and Evening Advertiser [1788], 27 Dec. 1791. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/Z2001423638/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=3&xid=512e5630. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

“UNDER THE MISTLETOE.—CHRISTMAS SONG.” Huddersfield Chronicle, 24 Dec. 1858, p. 3. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/R3210199889/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=3&xid=2b4ee1a7. Accessed 25 Nov, 2025.

“Mistletoe.” Daily Inter Ocean, 23 Dec. 1888, p. 11. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GT3003211964/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=11&xid=c41dc9e8. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

“UNDER THE MISTLETOE.” York Herald, 22 Dec. 1894, p. 12. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/R3215380734/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=12&xid=cd9fd51b. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

“Holly and Mistletoe.” Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 29 Nov. 1902, p. 2. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GR3217378321/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=14&xid=3f89999c. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

“The Neglected Mistletoe.” Grantham Journal, 29 Dec. 1906, p. 3. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/JF3230269777/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=3&xid=96b3c108. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

“First Mistletoe on Sale.” Sunday Times, 5 Dec. 1920, p. 15. The Sunday Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.manchester.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/FP1802469729/GDCS?u=jrycal5&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=15&xid=6445aac6. Accessed 15 Dec. 2025.

Further Reading

Mistletoe – Viscum album | Kew

The first Christmas card · V&A

Tenbury Mistletoe – About Tenbury

Lucio Biancatelli from WWF Italy, “Save that Robin”: a day in the fight against poaching in Northern Italy, 30th November 2022, SWiPE: https://stopwildlifecrime.eu/save-that-robin-a-day-in-the-fight-against-poaching-in-northern-italy/

Judith Bonzol, ‘The Death of the Fifth Earl of Derby: Cunning Folk and Medicine in Early Modern England’, Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme Vol. 33, No.4 (2010), pp. 73-100.

John Box, ‘Oaks (Quercus spp.) parasitised by mistletoe Viscum album (Santalaceae) in Britain’, British and Irish Botany 1 (1): 2019, pp. 39-49.

Johnathan Briggs, ‘The Festival Beginnings’, Tenbury English Mistletoe Enterprise, 2025, https://tenburymistletoe.org/teme

C. H. Coote, and Patrick Curry. “Blagrave, Joseph (b. 1610, d. in or before 1682), astrologer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. September 23, 2004. Oxford University Press. Date of access 24 Nov. 2025, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-2558>

Patrick Curry. “Culpeper, Nicholas (1616–1654), physician and astrologer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. September 23, 2004. Oxford University Press. Date of access 24 Nov. 2025, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-6882>

Alan Crawford. “Crane, Walter (1845–1915), illustrator, designer, and painter.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 10, 2013. Oxford University Press. Date of access 15 Dec. 2025, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-32616>

A. I. Finall, S. A. McIntosh and W. D. Thompson, ‘Subcutaneous inflammation mimicking metastatic malignancy induced by injection of mistletoe extract’, BMJ 2006;333:1293

Chloe Hughes, ‘Mistletoe auction goes ahead after flooding’, 26th November 2024, BCC News West Midlands

George R. Huntington and Megan L. Byrne, The holly and the ivy: a festive platter of plant hazards, BMJ 2021;375:BMJ-2021-066995

Ronald Hutton, Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain (Yale University Press, 2009).

Ronald Hutton, ‘Under the Spell of the Druids’, 13th June 2019, History Today: https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/under-spell-druids, accessed online 25/11/2025.

Michael Moss, MD, FAACT, Medical Director, Utah Poison Control Center, ‘Are My Holiday Plants Poisonous?’, Nov 13 2023, University of Utah Healthcare.

Andrew Nixon, ‘Orchards & Mistletoe’, Tuesday 4th January 2002, Herefordshire Wildlife Trust: ‘https://www.herefordshirewt.org/blog/andrew-nixon/orchards-mistletoe

Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (London, 2018).