Explore the visions, moods and story of artist Pearl Alcock in this post by JP.

Art loves to be incognito. Its best moments are when it forgets what it is called.

– Jean Dubuffet

I have been sitting in a room, day after day. So have you. It is a time of sitting in rooms, an age of it even. Sitting in a room is traditionally the preoccupation of painters. I sit in my living room thinking about painters. I have been drawn to the interior in painting for a long time. Literally, this means the still lives and the domestic portraits like those of Gwen John and Bonnard with his bath-dipped wife. It includes the wonderful out-of-the-window, New York paintings of Jane Freilicher. But really, I am thinking about something else.

I am thinking about my ideal painter. A painter of ideals. She paints with a lack of concern for what is traditionally understood as meaning. She paints the ‘experience of experience’, to use a John Ashbery phrase. It is linked to Boris Pasternak’s notion that living and being aware of being alive, is a business in itself. The specificities of functional adult life drive us away from this awareness constantly. Most of us have a kind of culturally encoded spiritual phobia of ‘doing nothing’, yet in Pasternak’s logic, it is an impossibility to be both alive and unproductive. Living is itself a productivity, a kind of music that conducts itself. ‘The experience of experience’ then, is the awareness of this music. That is what my ideal painter paints.

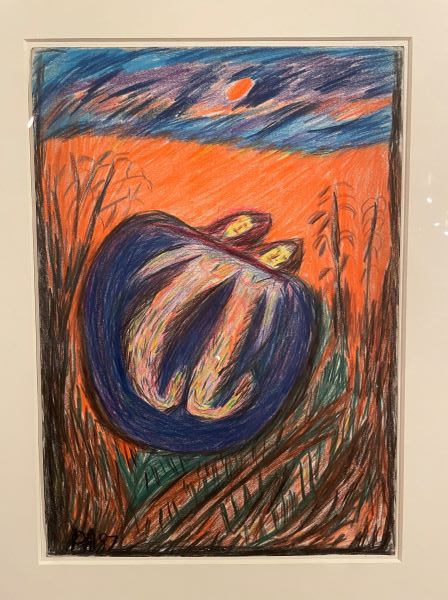

She might be called Pearl, the British-Jamaican painter of ‘visions and moods’. In her small flat in Brixton she painted endless fantasies of colour and rhythm. She was known by the art world as an ‘Outsider’, yet worked exclusively from the inside, the interior. She said “it’s like painting in space. Looking in some space and forming your own character, puzzle or what it is…each part of it is born of different things.”

Though her life was fascinating, I am thinking of her work. I’m not concerned with explanation or comment as much as with impulse and personality, by which I mean the evocation of colour. I am writing an essay, in the original sense of the word, an attempt. It will be a picture of its own process, which will be to give form to my own feelings toward the paintings of Pearl Alcock. It will be a love letter.

***

The picture starts in this room. I am watching a clip of Pearl and British Jazz/Blues musician-cum-art historian George Melly in conversation. It is an informal interview doused in cups of afternoon rum. They finger through stacks of Pearl’s paintings, most of which I’ve never seen before. Where are they now? Pearl says something beautiful, several times. She is talking about the gestures of the brush in the painting in her hands. The painting is her hands, it’s made from their movements, clearly.

She tells him, “when I move my hands like this, in swirls and swirling, it means I am smiling, and I’m singing, like something comes out of me and I take a little bit and I put it there, and I smile and I said, oh, you sweet child.”

I am thinking about ideal painters, because I can not write. I want to write poetry, but the more of it I have read, over the years, the more disappointing it has become. Art is disappointing when you’re an artist. Is that true? In the words of Dubuffet, “art does not lie down on the bed that is made for it.” The self-imposed pressure to need to ‘succeed’, to be compared, or at least for it to be worth it somehow, this art-making that is no longer a hobby or interest, seems to take you further and further away from what it is. So is it better not to be an ‘artist’ at all?

The ideas orbiting the world of ‘Outsider Art’, Dubuffet’s ideas particularly, seem fascinating to me now. I have ‘known’ about all this for years, but it wasn’t important until now, in this room. They are ideas of idealessness. A paradox, really, but a look at Pearl, and you see where art can come from when it doesn’t have a name. I would like to write about her, by writing after her.

Like Frank O’Hara, I am not a painter. That is perhaps the only thing I do share with the great poet, alas. But what I can do is form a picture with language. I can describe. And like Pearl, I can describe what is in my head as a landscape, a space. It is similar to the room I am in. It is chalky-bright. Winter-bright. It is filled with the kind of light you wouldn’t notice if you were outside. This is where I live, it’s home.

John Berger defined home as the place one sets off on adventures from. Adventure is a word I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about recently. Is it related to the french vent – ‘wind’? Or simply to the english advent – ‘the arrival of a notable person or thing’? I won’t check. I like the sense of both being possible. It is in that space of possibility that I want to cast off into. In an adventure one must be taken up, blown away. A long trip properly planned is rarely an adventure. A trip gone wrong, as long as one gets home in the end, invariably is. I meandre here in fidelity to my love for Pearl. She said a painting has to be “right for me. It has to be Pearl”. So my letter has to be me if it is to be for her. It has to be “full of love”.

Her love was for her friends. She ran a shebeen, a secret bar-come-refuge for the local black-caribbean queer community in the Brixton of the ’70s and ’80s. I’d like to sit and cover my eyes until a picture forms of her at work on Celebration of the Night. She will be working on it by lamplight, with all her friends in her mind. She will not picture them, but their presences. The spiritual residue of every conversation lit by what is most brilliant about each of them. The feelings are clear, but it is hard to paint such things.

I go on the memory of the hours and hours I spent invigilating the floor when the Pearl exhibition was on at the Whitworth last year. There is a huge difference in glancing at a picture and spending time with it. A huge difference again to spend day after day with one. It is like memorising a poem. It becomes you eventually, the productive idleness of someone else. What Pearl has put into the painting is stored there, like Egyptian honey, to be opened at any point in eternity. Honey always makes me think of the natural world when looked at with some awareness of its processes. Not just of flowers and honey-making things, but of glaciers and volcanoes and the formation of peat and salt. The world seen in this way is the world as made up of chains of images. It is incomprehensible to see even a fraction of them as simultaneous. I can barely hold two or three natural processes in my head at once, but even the smallest slice of the world, a suburban garden say, is full of millions of them.

Pearl’s painting is like this, though the processes are mental, spiritual even. They are layered on top of each other, each spinning in a cycle of feeling, of remembering having felt. There are glimmers of the visual details of a memory, but the picture is of remembering. What is depicted is the act of holding a memory in mind, all the music that comes off it, and the dance of the brush as it takes notes.

There is a generosity to the work of Pearl Alcock that strikes me as exemplary. Perhaps this is tied to her art’s origins in the making of birthday cards for friends. She couldn’t afford to buy them, so she drew them. She had never drawn before, or not as an adult, a full grown Pearl. Her friend liked it. She made more and grew fond of the act, slipped into the habit of making art. She began to draw scenes on scraps paper and card with crayons and felt-tips. She put them up in her Shebeen. Her friends adored them. The adoration of Pearl made Pearl grow proud of her visions. They asked her where they came from, this ‘Shy Girl’ and ‘Floating Mermaids’. They were like the myths and Old Testament stories but Caribbean, but Pearl. They were her own, she told them.

When she drew, the visions began to take form. She had been a seamstress and still thought of colour as thread. A felt tip could weave in a little, bit by bit. What came in the head, she would paint. She started in the centre and worked outward. Pattern would become form and the vision, gradually, would settle on the board. She told them the visions had always been there waiting to go up on the wall. Imagination, she said, is who we are. I mean, the pictures that live inside our heads are what is most alive about us.

She tried different techniques and materials. She tried something new in every picture. She liked trying something new, she said to Isaac, a regular. There’s a lot more new out there than there was in the old. Do it from your heart, and do it with good paint, and you’ll get a good reward.

Her friends were what was important in her life. She listened to them and they listened to her. That was the rule of the shebeen, listen. Isaac suggested they added look to the list of rules, look at these wonderful Pearls all over the place. An art dealer came eventually, a white woman. She told Pearl that she was a wonderful painter. Pearl looked at the jug filled with flowers in a furnace she’d painted only the week before, and said, “I don’t think you’ll see another one like it. Not even me can make another one like it.”

She thought more and more about dresses and scarves, about making patterns. Her visions started to look like blankets, rhythmic but not really repeated. It was like the way a thought can go round in your head, a repeating dream, that is the same but changing. These were the moods, she thought. Just paint the moods you have in front of you. The visions are still there behind them, like through a veil. They are not completely clear, so don’t paint them clear.

She drew enormous satisfaction in painting these. There was a sense of power that came with being in control of so much subtlety. She would not reveal everything, because life does not contain wholly revealed things. You must paint what is really in your life, which is lots of things all confused, but also singing.

I am thinking about painters and rooms, painters looking at rooms. I am no closer to any kind of resolution. There is no resolution, probably. A picture of Pearl at night, what will become Imagination is in its early stages in front of her. She is looking at the reflection of her cramped room in the dark window. She wants to make a picture of everything. She is feeling grand tonight, heroic. The outside is inside at night, a mirror. My whole life is outside the window, in memory, but all I can see is this room, and me sitting alone in it with rum. I am thinking about the paintings of Pearl.