In this post, Steph explores the history of the pineapple, from the first encounters Europeans had with the fruit to pineapple-themed décor in the past and the different ways the pineapple was used.

In the summer, pineapples are everywhere; they can be found on accessories, clothing, bath bombs, tableware, decorations for homes, toys and more. From the first time it was encountered by Europeans, the pineapple had a privileged position among fruits in Europe; once a symbol of opulence, it still brings to mind images of luxuries for many- images of a tropical holiday and fun by a pool. It may no longer be as luxurious as it once was in terms of being mostly exclusive to wealthy people- but we are still fascinated with it, in a sometimes slightly more kitsch or kawaii (the increasingly popular Japanese aesthetic of all things adorable and cute) way.

First Encounters

The ananas or pineapple, as it came to be known in English, originates from the Amazon basin, from where the Tupi and other indigenous peoples took specimens and spread it across parts of South America and across the Caribbean and the Bahamas. The word ananas comes from the Old Tupi word nana. Although Old Tupi is no longer spoken, the Tupi survived colonisation by Europeans; they be found today in isolated areas of Brazil and speak a language related to Old Tupi.

The arrival of Columbus and his crew in Guadeloupe is said to be the first time Europeans encountered pineapples. The medicinal benefits of the pineapple had already been known to various native peoples across a wide geographical area for some time. One of these groups, the Kalinago people, inhabited Guadeloupe at the time of Columbus’ arrival. It was in their settlements that Columbus and his men encountered the pineapple, with some pineapples eventually being transported to Spain. The Kalinago are now thought to have expanded outwards from the Amazon into Hispaniola, Jamaica and the Bahamas around 800CE, areas which had already been inhabited by the Taíno.

Columbus transported more than food and material goods back to Europe. According to Bartolomé de las Casas (who would transcribe and summarise the original Diaro of Columbus and fought against the exploitation and enslavement of indigenous peoples), upon Columbus’ first encounter with the Taíno on the island of Guanahani in the Bahamas, which he would refer to as ‘San Salvador’, Columbus had noted their astonishment at seeing swords. This was apparently in addition to their own lack of weapons and soon an opportunity was spotted. Diseases, such as smallpox, introduced by the Spanish and later other European colonisers to the ‘New World’ would also have provided the colonisers with another advantage, as native populations unfortunately would have had no immunity at all to these diseases. The six Taíno Columbus took with him would not be the last to be taken from their homes. When Columbus first encountered them, the Taíno could be found across the island of Hispaniola, now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, parts of Cuba, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas.

‘Weapons they have none, nor are acquainted with them, for I showed them swords which they grasped by the blades, and cut themselves through ignorance. They have no iron, their javelins being without it, and nothing more than sticks, though some have fish-bones or other things at the ends….It appears to me, that the people are ingenious, and would be good servants and I am of opinion that they would very readily become Christians, as they appear to have no religion. They very quickly learn such words as are spoken to them. If it please our Lord, I intend at my return to carry home six of them to your Highnesses, that they may learn our language. I saw no beasts in the island, nor any sort of animals except parrots.‘ – Extract from the journal of Christopher Columbus on Thursday 11th October 1492. [1]

It has often been said that few Taíno remained by the early-mid 16th Century- but many Spanish men had taken Taíno wives, so today they live on not just through language, music and artistic styles but also, as some studies have found, in the DNA of people who live in former Spanish colonies across the Caribbean.[2] There seems to have been something of a Taíno resurgence, with many now starting to proudly discuss their Taíno heritage in places like Puerto Rico- something which would have proved difficult or even impossible in the past due to racist stereotypes about the Taíno and other indigenous groups being somehow ‘backward’.[3]

A Taste of Luxury

Now back to the pineapple; one was eventually presented to King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, whose marriage had led to the unification of Spain. Although multiple pineapples had been sent to Spain, it was observed by Peter Martyr, an Italian who worked as a tutor to the Spanish princes, that most spoiled on the long voyage. In the case of those that did not spoil, the taste of the fruit met with the approval of the privileged few who were able to taste it- with some claiming that it was superior to other fruits in taste and appearance.

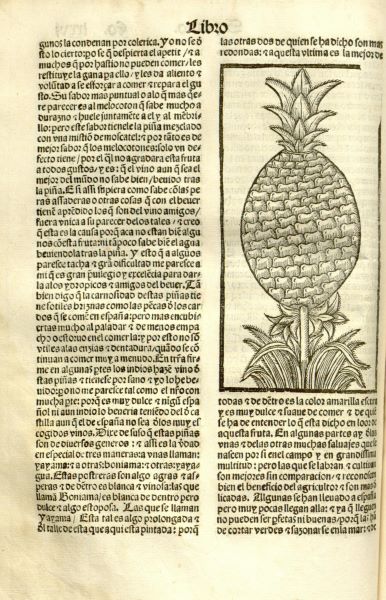

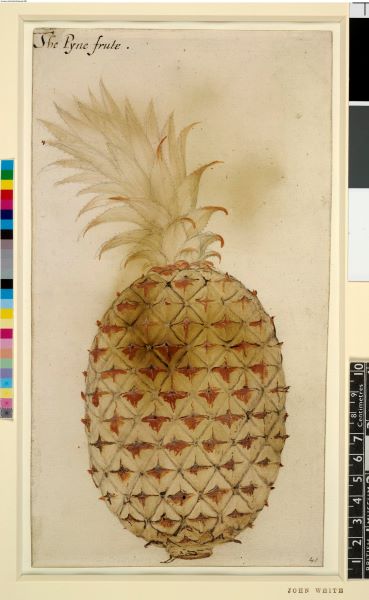

One commentator who had a lot to say about the pineapple and his own fondness for it was Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478-1557), a historian whose works about the ‘New World’ were admired in Spain and who was eventually appointed the royal chronicler of the Indies for Spain. Ovideo was included lots of woodcuts in the published versions of his works. One woodcut accompanied a description of the piña or pineapple, which he compared to the pinecone, from which it gets its Spanish name, and the artichoke in order to better enable his audience to imagine the fruit.[4] Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez notes that Oviedo was limited to a lengthy description of the fruit in order to convey the colours of a pineapple, as woodcuts were without colour, whereas the artist John White (1585-1593) would later create a better ‘naturalistic visual recreation of a pineapple’ in a watercolour drawing.[5]

Oviedo claimed that the pineapple had the power to both stimulate and restore the appetite. We do know that different indigenous peoples had used the pineapple to assist with fevers and stomach complaints. They also used the pineapple to make a kind of alcoholic drink. Although the taste of pineapple on its own usually met with the approval of the Spanish and other European colonisers, this pineapple wine apparently did not suit their tastes;

‘In some parts of Tierra Firne the Indians make wine from these pineapples and think it very healthy; I have drunk it and it is nowhere near as good as ours because it is very sweet, and no Spaniard nor Indian would drink it if they had Castilian wine, though the wine of Spain is not among the most select.’ – Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. [6]

It seems that, for Europeans, the main appeal of the pineapple was not in any medicinal properties it might have but instead its strange appearance and its taste. Oviedo was of the opinion that it was the most beautiful of all fruits and had plenty to say about its beauty. He also discussed the different cultivars or varieties he knew of and his own failed attempts to transport the fruit and plants back to Spain.

So many fresh pineapples and the plants from which they grew would spoil on the lengthy journey to Europe that, until the invention of the steamboat in the 19th century, the pineapple (particularly when fresh) was consumed and enjoyed largely by those who had plenty of money to spare in Europe. As a result of this and the difficulties horticulturalists faced in growing the fruit in Europe, in addition to the money required to do grow pineapples in Europe, the pineapple became associated with luxury and lavish dining in Europe. Kaori O’Connor in Pineapple: A Global History discusses the use of the imagery of the pineapple at banquets at Versailles during the reign of Louis XIV, known as the ‘Sun King’; she describes pineapples made of sugar and later the use of preserved pineapples (which had been brought in from French colonies) in ice creams and sorbets.[7]

Across the English Channel, the Sun King’s cousin Charles II was painted receiving a pineapple from royal gardener John Rose- although this is quite the misleading image for a number of reasons. Firstly, there are multiple copies of the painting. The one in the possession of The Royal Collection Trust is thought to date to some time between 1675-1680, with one at Ham House (owned by The National Trust) being an 18th century reproduction. [8] [9] Another version of painting, attributed to Hendrick Danckerts, dates to 1677 and is kept at Houghton Hall. Secondly, the date range of the two 17th century paintings puts them before the first pineapple being successfully grown from slips in Europe, which occurred two years after Charles II died in 1685. Thus the pineapple in the painting can only have been an imported one. Still, it must have been impressive; an imported pineapple would show the influence this king wielded overseas, specifically in England’s Caribbean colonies such as Barbados and perhaps to a lesser extent, with England’s power over the island further secured during his reign, Jamaica.

John Rose (1619-1677), the Royal Gardener, presenting a Pineapple to King Charles II (1630-1685) (after Henry Dankerts) by Thomas Stewart (1766 – c.1801) ©National Trust Images. Painting kept at Ham House. Source: The National Trust

During the reign of Charles II, the pineapple was referred to as the ‘king pine’ in England, further reinforcing the status of the pineapple as a symbol of luxury- much like those that had made their way to Versailles. The pineapple had sometimes been referred to as ‘the princess of fruits’ during the reign on Elizabeth I. This description is said to have first been given to it by none other than Sir Walter Raleigh.[10] The various versions of the painting of Charles II being presented with a pineapple by John Rose have been the subject of some speculation; The Royal Collection Trust suggests that the 1677 version may have been intended to commemorate the death of the Royal Gardener, who died that year.[11] Some have suggested that the pineapple in the painting might hint at desire, as the garden in which Charles II stands is that of the Duchess of Cleveland, one of the king’s mistresses, and John Rose had apparently worked on her estate.[12] The Duchess had a hothouse, which would have been used to make the pineapple ripen.

In the Caribbean colonies claimed by European powers, plantation owners were busy dining on fresh tropical fruits and using enslaved people to produce another sweet luxury, which brought them large amounts of wealth; sugar. Although pineapple plantations did not yet exist and so were not yet grown as a plantation crop like sugar cane, we do know that plantation owners in European colonies dined on them and that sugar was used to help preserve pineapples (often in a sort of syrup) in order to send them to Europe. Wimmler writes that pieces of pineapple preserved in sugary liquid, known as confiture liquide, were available in French apothecaries which hinted at ‘their exotic nature and supposed medicinal properties’ but confitures ‘fetched higher prices in France and can be described as luxury products’.[13] Preserved pineapple in confiture on its own were not the only ways in which the pineapple was enjoyed by Europeans; in Tastes of Empire: Foreign Foods in Seventeenth Century England , Jillian Azevedo describes recipes which used the pineapple in pastries or called for it to be boiled with meat.

In addition to becoming increasingly associated with the dishes consumed by the wealthy and the amount of influence various European powers exerted abroad, the image of the coveted pineapple was, unsurprisingly, sometimes intertwined with images of enslaved people.

One of the most famous instances in which the pineapple was linked to the enslaved and the wealth amassed as a result of the Transatlantic slave trade is the ‘Barbados Pineapple Penny’, sometimes just referred to as the ‘Barbados Penny’. First minted in 1788, it shows an image of a crowned slave on one side with the phrase ‘I serve’ and, on the reverse side, a pineapple. According to Stephan Lenik and Christer Petley, 5367 of these pennies were produced and ‘many of these, as well as the ‘Barbados Neptune Penny’…remained in circulation in Barbados into the early twentieth century’.[14] Royal Museums Greenwich state that the coins were ‘struck locally’ but ‘were never recognised as an official colonial currency’, so the coin is often referred to as a form of token.[15] It’s believed that plantation owner Sir Philip Gibbes commissioned the penny. But why were these coins in circulation if they were not official legal tender? It turns out that British currency was not particularly well established or used much in Barbados and other British colonies in the Caribbean until the late 19th century, with Spanish currency often being used.

An Expensive Hobby

As we have already established, growing pineapples and bringing them to fruit in Europe would prove to be quite a challenge. Agneta Block is thought to have been the first to bring a pineapple to fruit in Europe, accomplishing this feat in 1687. According to O’Connor, Block used pineapple slips from the Horticultural Gardens at Leiden as the propagation material for her pineapple.[16] She promptly commissioned a silver medal to celebrate her achievement, which proclaimed that ‘Art and Labour have achieved what Nature cannot’. One side of the medal depicts Block herself, the other shows the goddess Flora in the foreground. Flora holds a tulip aloft in one hand and a bouquet of various flowers in the other, off to the side is a potted pineapple plant alongside a potted cactus- hinting at Agneta’s other achievements.

A ‘slip’ is a stem which protrudes from the main stalk of the mother plant, just underneath the base of the fruit. Other methods of growing pineapples are to use the crown of the fruit itself or to use a ‘sucker’- which are ‘pups’ or smaller plants which form along the main stem away from the fruit and between leaves along the stem.

Agneta had used the money she inherited following the death of her first husband, a wealthy silk merchant, to buy a country estate and establish a botanical garden equipped with various greenhouses.[17] These greenhouses were used to rear exotic specimens she had collected for her by the Dutch East India Company or VOC, as well as specimens she had obtained from the Horticultural Gardens at Leiden. In the case of her pineapple, Garritt Van Dyke states that the cutting or slip she used was probably ultimately transported from Surinam, which was then a Dutch colony, in 1680.[18]

The initial results of the first endeavours to bring pineapples to fruit in Europe were small and not particularly appetising at first, so imported fruits were still the only pineapples being consumed. Due to innovations in hothouse technology it was eventually possible for the very wealthy to grow pineapples people could consume. An emphasis was sometimes placed on the superiority of homegrown pineapple, owing to its freshness.

However, even the wealthy nobility and gentry might turn to markets for some fruit and vegetables or to the large commercial nurseries that emerged during the 18th century. Such establishments could sell or rent out pineapples to those who had a fair bit of money to spend but did not have their own pinery, so that a pineapple might grace their tables and impress their guests too. The experience of having a pineapple at the table was not just about simply eating something that cost a lot of money and few would have tasted (at least without being preserved in sugary syrups) into the early 19th century, but the spectacle of having one at all.

Bringing pineapples which were still growing and needed to be kept in hot beds around the clock out for a viewing wasn’t exactly practical (or glamorous considering the amount of manure sometimes involved in the growing process.) The pineapples which came from the hothouses of the wealthy might occasionally be served up in extravagant displays of wealth to guests the owner desired to impress or this produce, too, might simply serve as a form of decoration to show that they could produce such a thing. Even royalty didn’t dine on fresh pineapple all the time, presumably due to the amount of work and costs involved in producing a fresh pineapple; in An Economic History of the English Garden, Roderick Floud notes that ‘there was a special treat of a pineapple’ at the table of King George III on Christmas Day 1783, which suggests that pineapples were still a luxury even for royalty.[19]

In Britain, those who were well off enough to engage in what was an extremely expensive hobby also found other ways to show off their pastime and wealth; stone pineapples might indicate that you could afford to have your own pinery or that you were in on the trend for pineapples in general. Pineapples also appeared on wooden furnishings, such as carved pineapples on wooden bed posts and finials.

Having a real pineapple on the table wasn’t the only way to enjoy one during the dining experience; in the mid-18th century, Josiah Wedgwood and Thomas Whieldon produced ceramics made to look like pineapples. These ranged from sugar bowls to tea caddies, teapots and more. Again, the pineapple was intertwined with colonialism, although perhaps inadvertently, as some of the goods these ceramics were made to hold were the fruits of empire. Much like real pineapples, these ceramics were themselves luxury goods and as such quite expensive.[20] Pineapple themed ceramics were quite popular among those who could afford them and those produced by the likes of Wedgwood and Whieldon were even exported to Britain’s American colonies. The cauliflower also inspired similar (and popular) designs by Wedgwood and Whieldon but the yellow and green glaze of the pineapple ceramics seems to have been especially popular.

Pineapples also found their way onto textiles, such as the piece of silk brocade from the Whitworth’s collections pictured above and below. It is French in origin, estimated to date back to around c.1710-1735 and is decorated with a complicated design of palms and pineapples bordered with a lace pattern. With the earliest estimated date being 1710, this elaborate brocade could possibly date back to the last years of the Sun King’s reign (Louis XIV died in 1715) or to the reign of his successor; his great-grandson Louis XV, who (like his great-grandfather) became king of France when he was still a young child. Although pineapples may have graced the table of Louis XIV in various forms, it would not be until the reign of Louis XV that a royal hothouse was built specifically for pineapples.

Louis XIV initially encouraged the production of silk in France during his reign but, through revoking the Edict of Nantes in 1685, inadvertently allowed the silk industry (and other industries) in England to benefit when skilled Huguenot silk-weavers sought refuge across the English Channel. This yellow brocade is certainly an elaborate, perhaps more subtle and tasteful incorporation of the pineapple into a textile design. It’s a far cry from the cheaply made summer wear which brings the pineapple to our high street stores every year. I think this fabric likely wouldn’t have been within the reach of the average person.

As beautiful as this brocade is, even more fascinating is the fact that pineapples weren’t just a decorative motif for textiles; sometimes they became the textiles themselves, as we shall see in part 2 of this blog.

References

[1] Paul Halsall, Fordham University Medival Sourcebook. Christopher Columbus: Extracts from Journal [https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/columbus1.asp], adapted from Julius E, Olson and Edward Gaylord Bourne, The Northmen, Columbus, and Cabot, 985-1503, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF THE VOYAGES OF COLUMBUS, edited by Professor Edward G. Bourne, pp. 77.

[2] Robert M. Poole. ‘What Became of the Taíno?’ in Smithsonian Magazine (October, 2011) [https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/]

[3] Poole. ‘What Became of the Taíno?’ in Smithsonian Magazine.

[4] Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez , ‘Description and Representation in Oviedo’s and Staden’s Travel Accounts of the New World’ in Lauren Beck and Christina Ionescu Visualizing the Text: from Manuscript to Culture to the Age of Caricature (University of Maryland Press, 2007), pp. 150-151.

[5] Pérez , ‘Description and Representation in Oviedo’s and Staden’s Travel Accounts of the New World’ in Lauren Beck and Christina Ionescu Visualizing the Text: from Manuscript to Culture to the Age of Caricature (University of Maryland Press, 2007), pp. 150.

[6] Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, passage from Historia General Y Natural in Kathleen Ann Myers (with translations by Nina M. Scott), Fernández de Oviedo’s Chronicle of America, (University of Texas Press, 2007), pp. 163-164.

[7] Kaori O’Connor, Pineapple: A Global History (London, 2020), pp. 30-31.

[8] https://www.rct.uk/collection/406896/charles-ii-presented-with-a-pineapple

[9] https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1139824

[10] Sir Walter Raleigh in The Discoverie of the Large, Rich and Bewtifvl Empire of Gviana, With a Relation of the Grat and Golden City of Manoa (Which the Spaniards Call El Dorado) And the Prouinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia and other Countries, with their Riuers, Adioyning. Performed in the Yeare 1595 by Sir W. Ralegh, Knight, Captaine of Her Maiesties Guard, Lo. Warden of the Stanneries, and Her Hignesse Lieutenant Generall of the Countie of Cornewall. London: Robert Robinson, 1596. pp. 1-120 (in) The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana … by Sir W. Ralegh … Reprinted from the Edition of 1596 With Some Unpublished Documents Relative to That Country. Edited by R.H. Schomburgk. The Hakluyt Society, Series 1, Number 3. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1848. Accessed online at [https://nutritionalgeography.faculty.ucdavis.edu/sir-walter-raleigh-caribbean-exploration/] Nutritional Geography, a project created by Dr Louis E. Grivetti Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Davis Nutrition Department.

[11] https://www.rct.uk/collection/406896/charles-ii-presented-with-a-pineapple

[12] O’Connor, Pineapple: A Global History (London, 2020), p. 21.

[13] Jutta Wimmler, The Sun King’s Atlantic: Drugs, Demons and Dyestuffs in the Atlantic World, 1640-1730 (Leiden, 2017), pp. 88-89.

[14] Stephan Lenik and Christer Petley, ‘Introduction: The Material Cultures of Slavery’, in Christer Petley and Stephen Lenik (editors), Material Cultures of Slavery and Abolition in the British Caribbean (Abingdon, 2017).

[15] https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-255103

[16] O’Connor, Pineapple: A Global History (London, 2020), p. 7.

[17] Garritt Van Dyke, ‘Plants as Luxury Foods’ in Jennifer Milam (ed.), A Cultural History of Plants in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (London, 2022), pp. 63-64.

[18] Van Dyke, ‘Plants as Luxury Foods’ in Jennifer Milam (ed.), A Cultural History of Plants in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (London, 2022), p. 64.

[19] Roderick Floud, An Economic History of the English Garden (London, 2019), pp.255-256.

[20] Fran Beauman, The Pineapple: King of Fruits (New York, 2011), pp.111-112

Bibliography

Rijksmuseum: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/NG-VG-1-1812

The Royal Collection Trust: https://www.rct.uk/collection/406896/charles-ii-presented-with-a-pineapple

The National Trust: https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1139824

The Royal Collection Trust: https://www.rct.uk/collection/406896/charles-ii-presented-with-a-pineapple

Revealing Histories: remembering Slavery: A Partnership Project from Eight Museums in Greater Manchester: http://revealinghistories.org.uk/africa-the-arrival-of-europeans-and-the-transatlantic-slave-trade/objects/barbados-penny.html

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (Smithsonian): https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2018.17.13?destination=/explore/collection/search%3Fedan_q%3D%252A%253A%252A%26edan_fq%255B0%255D%3Dplace%253A%2522Barbados%2522%26op%3DSearch

Jillian Azevedo, Tastes of the Empire: Foreign Foods in Seventeenth Century England (Jefferson, 2017).

Karen F. Anderson-Córdova, Surviving Spanish Conquest: Indian Fight, Flight and Cultural Transformation in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico (University of Alabam Press, 2017).

Fran Beauman, The Pineapple: King of Fruits (New York, 2011).

Charlotte Boyce and Joan Fitzpatrick, A History of Food in Literature: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present (London, 2017).

F. Carl Braun, ‘A Triple Numismatic Enigma of the Nineteenth Century Caribbean: Haiti, Barbados, St Kitts or Vieques’, in Richard G. Doty and John M. Kleeburg (editors), Money of the Caribbean: Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society (New York, 2006), pp. 117-190.

Dave DeWitt, Precious Cargo: How Foods From the Americas Changed the World (New York, 2014).

Garritt Van Dyke, ‘Plants as Luxury Foods’ in Jennifer Milam (ed.), A Cultural History of Plants in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (London, 2022), pp. 51-68.

Roderick Floud, An Economic History of the English Garden (London, 2019).

Paul Halsall, Fordham University Medival Sourcebook. Christopher Columbus: Extracts from Journal [https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/columbus1.asp], adapted from Julius E, Olson and Edward Gaylord Bourne, The Northmen, Columbus, and Cabot, 985-1503, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF THE VOYAGES OF COLUMBUS, edited by Professor Edward G. Bourne, pp. 77.

Joy Kearney, ‘Agnes Block, a Collector of Plants and Curiosities in the Dutch Golden Age, and her Friendship with Maria Sibylla Merian, Natural History Illustrator’, in Susan Bracken, Andrea M. Gáldy and Adriana Turpin, Women Patrons and Collectors (Newcastle upon Tyne, 2012), pp. 67-82.

Stephan Lenik and Christer Petley, ‘Introduction: The Material Cultures of Slavery’, in Christer Petley and Stephen Lenik (editors), Material Cultures of Slavery and Abolition in the British Caribbean (Abingdon, 2017).

Kathleen Ann Myers (with translations by Nina M. Scott), Fernández de Oviedo’s Chronicle of America, (University of Texas Press, 2007).

Kaori O’Connor, Pineapple: A Global History (London, 2020), pp. 30-31.

Gary Y Okihiro, Pineapple Culture: A History of the Tropical and Temperate Zones (University of California Press, 2009).

Ruth Levitt, ”A Noble Present of Fruit’: A Transatlantic History of Pineapple Cultivation’, Garden History 42:1 (2014), pp. 106-119.

Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez , ‘Description and Representation in Oviedo’s and Staden’s Travel Accounts of the New World’ in Lauren Beck and Christina Ionescu Visualizing the Text: from Manuscript to Culture to the Age of Caricature (University of Maryland Press, 2007), pp. 145-170.

Robert M. Poole. ‘What Became of the Taíno?’ in Smithsonian Magazine (October, 2011) [https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/]

Sir Walter Raleigh in The Discoverie of the Large, Rich and Bewtifvl Empire of Gviana, With a Relation of the Grat and Golden City of Manoa (Which the Spaniards Call El Dorado) And the Prouinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia and other Countries, with their Riuers, Adioyning. Performed in the Yeare 1595 by Sir W. Ralegh, Knight, Captaine of Her Maiesties Guard, Lo. Warden of the Stanneries, and Her Hignesse Lieutenant Generall of the Countie of Cornewall. London: Robert Robinson, 1596. Edited and uploaded by Dr Louis E. Grivetti, Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Davis Nutrition Department, for the Nutritional Geography project: https://nutritionalgeography.faculty.ucdavis.edu/sir-walter-raleigh-caribbean-exploration/

Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food, (Oxford, 2009).

Jutta Wimmler, The Sun King’s Atlantic: Drugs, Demons and Dyestuffs in the Atlantic World, 1640-1730 (Leiden, 2017).

I’m hard of reading

Would love this as audio

Looks really interesting

LikeLike

Thanks for your feedback Kez! Producing audio files of various works can take a while. We’ll see what we can do.

LikeLike