In this post, Steph looks at the artistic omission of Henry V’s facial scar and the story of how he got it.

On the 31st August 1422 King Henry V died. He is thought to have become ill during the Siege of Meaux earlier that year. Far from being the glorious affair we sometimes envision as we pretend to be knights during childhood play, medieval warfare (like any kind of warfare, really) was quite horrible. Dysentery and other nasty diseases spread easily in large camps. Outbreaks of dysentery could wipe out a good portion of your men before the enemy could, which is what happened to Henry’s forces before Agincourt in 1415. And Agincourt and victory is what comes to our minds when we talk about Henry V. He appears to be giving his rousing speech before the Siege of Harfleur in Shakespeare’s Henry V on the piece of furnishing fabric pictured above, which is often how so many of us imagine him; about to jump into the fray and emerge victorious, urging his men on.

He was far from the reluctant fighter we see in Netflix’s The King, which borrows a lot from Shakespeare, such as; the character of Falstaff, who was not a real person. Falstaff in The King dies a noble death and is not as much of a ne’er-do-well character as the original. Timothée Chalamet’s portrayal of Henry in The King reluctantly engages in one-to-one combat in an effort to avoid wider conflict and save his brother Thomas from having to fight Hotspur. Although Henry wins the fight, Thomas gets angry about his brother stealing what he views as a chance to gain glory and goes on to die an offscreen death, which we are told occurred when Thomas went off to fight against the Welsh. None of that ever actually happened. Henry sports a mark on his left cheek during the film, which may perhaps be a nod to the real Henry’s scar but in The King he doesn’t gain it at Shrewsbury.

As the The King takes so much from Shakespeare’s Henriad plays and reworks aspects of them, inaccuracies are to be expected. They’re to be expected with many films set in the past, really. I’m not going to pick the film apart but you can find lots of articles that do. That’s not to say that I didn’t enjoy the film, I did like it!

The Wound

With a few exceptions, whenever we see Henry V on stage or on our screens he almost always lacks the scar we know he must have had. It would be foolish to think that no other monarch had scars or other marks on their person, of course. Their portraits were idealised versions of the real thing. Even with monarchs who did not participate in combat, popular pastimes such as hunting came with their own risks and some diseases, such as smallpox, could also leave their mark. So could the white lead makeup some monarchs wore. However, the story behind Henry V’s scar is an incredible one which rarely makes it onto our stages or on screens.

Shakespeare mentions that Henry was wounded in battle and carried on fighting in Henry IV but there are scant details of what Prince Hal refers to as a ‘scratch’. You don’t often see a scar on Henry’s face in many adaptations of Shakespeare’s Henry V, either. Laurence Olivier’s portrayal of Henry has a face without blemish, like many others before and since. His version of Henry V aimed to boost morale during the Second World War. Perhaps that helps to explain the lack of a scar?

When Henry was Prince of Wales, he was injured fighting against Henry Percy, also known as Hotspur, at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. The Percys had been allies of his father Henry IV in his effort to dethrone his cousin Richard II but they eventually turned against the new king. No one knows when Henry V was actually born because he was never intended to be king. He was born at Monmouth Castle in either 1386 or 1387, so he was around sixteen years old when he fought at the Battle of Shrewsbury.

The young Prince of Wales took an arrow to the face. He is said to have kept on fighting but after the battle it became clear just how serious the wound was. The wooden shaft of the arrow was removed but the arrowhead remained lodged in bone. He was saved by the genius of surgeon John Bradmore, who designed a special tool to remove the arrowhead. According to Bradmore’s account, it had embedded itself six inches into Henry’s head. He used wooden dowels or piths, wrapped in cloth and dipped in honey, to open up and clean Henry’s wound. He also massaged the prince’s neck in order to try to prevent seizures once he had removed the arrowhead.

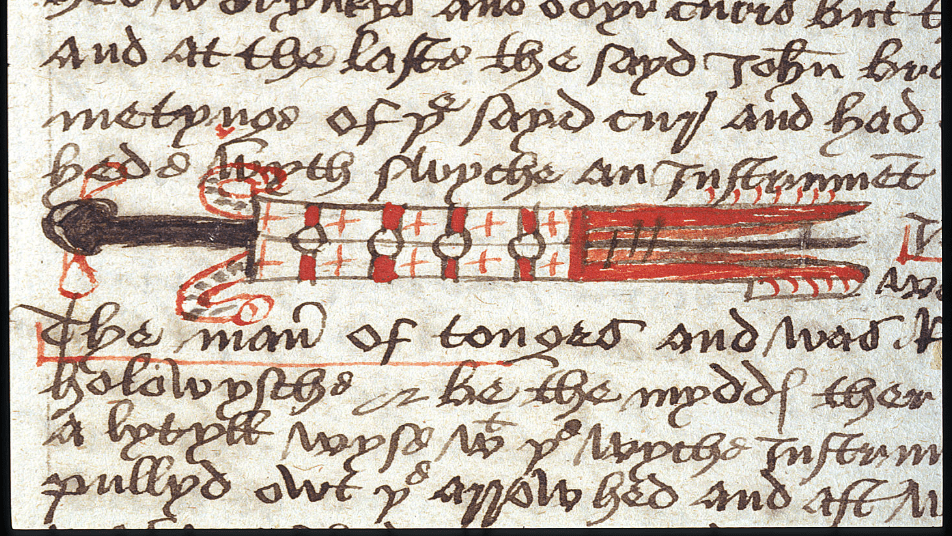

The tool he designed to remove the arrowhead took the form of a special pair of tongs, which were inserted into the wound and then the hollow end of the arrowhead. At the turn of a screw, they were made to create a tight grip within the arrowhead. This enabled Bradmore to extract the offending object. He continued to clean the wound with smaller implements each day in order to give it time to close, which took around twenty days. We have a good idea of what the tongs Bradmore designed looked like because of a description of the tool in his own account and a drawing in the manuscript, as well as a drawing in the account of his pupil and successor as royal surgeon, Thomas Morestede. The image above is from a Middle English translation of Philomena and other works by John Bradmore, which dates back to arround 1446, in The British Library’s Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

The King’s Image

Artistic omission of the scar Henry would have been left with goes back quite a long time. According to Bradmore, the wound was on the left side of Henry’s face, near the nose. Henry is depicted with the left side of his face exposed in the posthumous portrait you can see above, however, prompting many to suggest that Bradmore was referring not to Henry’s left but his own. Perhaps it was just omitted because the portrait was made to present an idealised version of the king and/ or because it was produced after his death. It has been noted, however, that a portrait of an English king in profile is very unusual.

The scar is also absent from a miniature of Henry in a later copy of Thomas Hoccleve’s The Regiment of Princes in The British Library’s Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, dated to around 1411-1432. The poem was written by Hoccleve for Henry when he was Prince of Wales and follows the popular medieval theme of giving advice to rulers.

Henry’s scar doesn’t seem to have been mentioned much in writing, except when his injury was discussed in later centuries as a testament to his masculinity, marking his passage into adulthood. The true extent of the scar is unknown but it’s unlikely that such an injury did not leave him with at least a small scar that was somewhat noticeable. Many of us have gained scars from injuries that were far less serious.

Henry obtained the scar as a result of battle and so you might expect it to be interpreted in a favourable manner, even though it was not included in idealised depictions of Henry. By contrast, Richard III’s twisted spine would be interpreted after his death as the mark of an evil character in an England ruled over by the Tudor dynasty.

Various conditions and marks on the human body were sometimes interpreted as indicators of a corrupt character or they were sometimes believed to have been caused by something that their parents had done or imagined when they conceived. Another cause for certain conditions or certain aspects of one’s physical appearance was thought to be something the mother had seen whilst she was pregnant. Shakespeare has a bit of fun with such theories when Henry V woos Katherine.

King Henry: Now, beshrew my father’s ambition! He was thinking of civil wars when he got me; therefore was I created with a stubborn outside, with an aspect of iron, that when I come to woo ladies, I fright them. (Henry V, Act 5, Scene II)

Henry V’s posthumous legacy has been much kinder to him than Richard III’s, even though various groups in the twenty-first century have put him ‘on trial’ for actions such as giving his men the order to kill French prisoners at Agincourt in 1415. If we’re comparing the two kings, it’s hard to decide who had the worst death- although dysentery, often suggested as a probable cause of death for Henry V, might take the crown as the more embarrassing of the two if we ignore a certain wound inflicted upon Richard III (thought to have been carried out after his death). English history certainly has a few characters to choose from if you’re looking for a villain or a ‘bad’ king, but many people would still not classify Henry V as such. This is partly due to how others perceived him when he was alive. He had a reputation for being pious, for example, which earned him respect then, but is less exciting to many a twenty-first century audience.

It’s also thanks to Shakespeare and others that Henry has become part of our national myth. He has become symbolic of the English spirit triumphing over great odds. His forces really were outnumbered at Agincourt, but Shakespeare’s words are those we often recall when we think about that battle. Shakespeare was writing during the reign of Tudor queen (Elizabeth I) when he wrote Henry V, which is thought to have been written around 1599. Much like Henry V, Elizabeth I has also become part of our national myth. The Tudors were descended from the Lancastrian branch of the House of Plantagenet and also from Edmund Tudor, who was the half-brother of Henry VI (Henry V’s son). You might say that, like Henry V’s father, the Tudors (specifically Henry VII) had usurped the throne.

Henry V’s scar may not have been compatible with certain artistic ideals of beauty and how royalty should be portrayed during his lifetime and in later centuries. Although it doesn’t appear to have been vividly described or even mentioned much, anyone who met Henry and was aware of how he got the scar, regardless of how large it was, may well have been quite impressed that he had survived such an injury. He could have easily died in 1403 and others who did not have the benefit of receiving such good medical care most likely would have perished. So at the very least, the scar indicated he had access to a fantastic surgeon!

The 2011 play ‘The King’s Face’ focused on Henry’s wound and the surgery performed by Bradmore. It presented, perhaps, an arguably more human Henry than Shakespeare and many others.

Today many have their image carefully curated in our increasingly online world. It creates a lot of pressure. There is also a growing culture of body positivity. If you were an artist, would you depict Henry with his scar?

Resources

You can flick through a copy of Thomas Hoccleve’s ‘The Regiment of Princes’ on The British Library’s website here:

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-regiment-of-princes

You can also view a detailed record for manuscript Harley 1736 , with illustrations, in The British Library’s Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts and a detailed record for manucript Arundel 38.

https://thekingsface.wordpress.com/

Christopher Allmand, Henry V, (London, 1997).

Stephen Cooper, Agincourt: Myth and Reality 1415-2015 (Barnsley, 2015).

Julie Crawford, Marvellous Protestantism: Monstrous Births in Post-Reformation England (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

Anne Curry, Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations (Woodbridge, 2000).

Anthony Davies, Filming Shakespeare’s Plays: The Adaptations of Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Peter Brook and Akira Kurosawa (Cambridge, 1994).

Ilana Krug, ‘The Wounded Soldier: Honey and Late Medieval Military Medicine’, in Larissa Tracy and Kelly DeVris (editors), Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture (Leiden, 2015), pp. 194- 214.

S.J. Lang, ‘John Bradmore (d.1412)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2008)[https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-45759].

Michael Livingston, ‘”The Depth of Six Inches”: Prince Hal’s Head-Wound at the Battle of Shrewsbury’, in Larissa Tracy and Kelly DeVris (editors), Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture (Leiden, 2015), pp. 215-30.

John Matusiak, Henry V (London, 2013).

Ian Mortimer, ‘Henry V: The Cruel King’, History Extra: https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/henry-v-the-cruel-king/ (2009)

Ian Mortimer, Henry V: The Warrior King of 1415 (London, 2013).

Craig Taylor, ‘Henry V, Flower of Chivalry’, in Gwilym Dodd (editor), Henry V: New Interpretations (York, 2013), pp. 217-248.

Malcolm Vale, Henry V: The Conscience of a King (London, 2015).

Jeffrey R. Wilson, Stigma in Shakespeare Project- Henry V’s Face in Early English Literature:

beautiful article

LikeLike